Data-driven delivery: the simple science behind the best presenters

The PowerPoint presentation. Three words which unfortunately in the modern workplace have come to evoke the feelings of homework at school… asked for routinely. Delivered routinely – or nervously, apologetically, unpreparedly… take your pick.

The sheer volume of presentations (latest estimates suggest there are 35 million presentations delivered every day worldwide), the bad practices that have crept in, and the poor experiences of being on the receiving end of so-called death by PowerPoint, all play a part in what many participants in our training tell us. Namely, presentations are approached as something to survive, rather than an opportunity to thrive.

Our mission, as trainers, is to revitalise the power of this medium of communication. And to recognise its ability – when done well – to achieve 3 things:

- to showcase your team’s work

- demonstrate the value your function brings to the mix, and finally

- to enhance your professional credibility in the eyes of your audience

But isn’t being a confident public speaker something you are just born with?

The majority of people we work with tell us they fear public speaking or that it does not come naturally to them. But presenting well, and having confidence in doing so, are skills that can be learnt. Our training moves these skills away from the subjective, by putting objective data behind some of the tools we teach – some simple science behind the art of communication.

Slow down, let me hear you

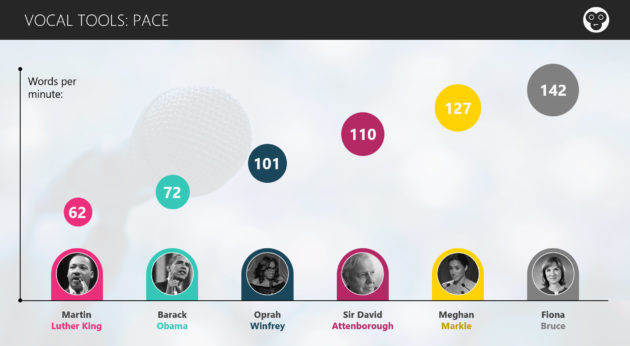

Studying the common traits of the great orators is helpful for anyone wishing to improve as a speaker. The first trick you will notice is that when it comes to the big moments or the key messages, good communicators use a very deliberate, slower pace of delivery.

The average person speaks at 180 to 200 words per minute (wpm) in everyday conversation. But as our chart below shows, when Barack Obama wants to land something, he takes it down to 112 wpm. Martin Luther King talked at 62 wpm during the opening of his ‘I have a dream’ speech in 1963. Steve Jobs, unveiling the iPhone in 2007, delivered the big bang moments at between 54 to 85 wpm. Sir David Attenborough purrs at 110 wpm.

The trick we use to bring this home in our sessions is very simple. We surreptitiously put a stopwatch on you during a presentation. Then we can tell you how you measure up to the greats.

The winner in 4 years of testing (meaning the slowest speaker) clocked 92 wpm. The fastest (meaning the loser) pushed 350 wpm, 6 words a second. And when asked to remember what he said he could not, which proves immediately that you have to give your audience time to hear what you have to say. Otherwise, your messages will be at best diluted, at worst, lost entirely.

Not to say that all we have to do is speak slower. ‘One-paced’ slow is as bad as one-paced fast. Variety is what you come to realise all the greats use in their voices to keep the audience engaged, and to sound human, not forced. So try finding key words to land by slowing right down, but also identify the moments where you can up the rate. The difference in impact on the audience is remarkable.

The voice is your instrument, don’t take it for granted

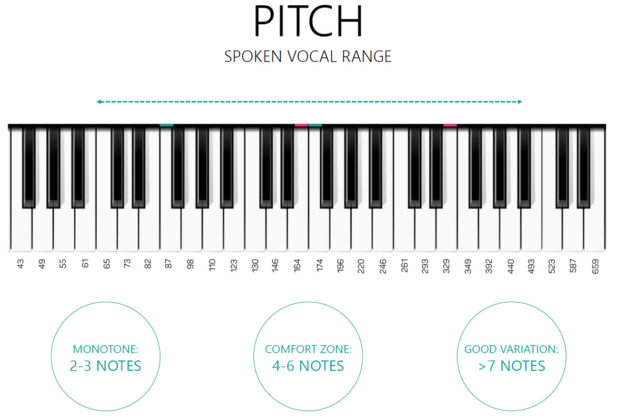

The second crucial test of a speaker’s vocal skills also has to do with variety – this time, pitch.

Most people avoid the dreaded monotone voice. But very few use the wonderful instrument we all have to full effect, to achieve real impact. Trying to coach vocal range has always been one of the hardest elements to get through in a demonstrable and effective way.

Until, that is, we were lucky enough to come across a pitch analysis app on our phone. With this, we are able to show participants a graph of what their voice looks like as they speak (not just how it sounds) and record their patterns and pitch range in Hertz. We then translate this into a span of notes on a piano keyboard. The bigger the span, the more range there is in someone’s voice.

Many hours of research and thousands of recordings later, and we can tell you a monotone voice comes in at 2 to 3 notes. Good orators will typically have an expressive range of 7 to 10. But the vast majority of people we train are in the comfort zone of 4 to 6 notes. In other words, not quite doing enough to really engage this powerful tool of communication, to carry your words to your audience with confidence. And for those people, we can support with exercises to really expand their pitch range. Even a jump from 5 to 7 makes a significant difference from an audience perspective.

Science meets art

In a data age, where wearable technologies are everywhere, we increasingly find our analytics tools achieve deeper understanding of the theory, and faster improvements in practice.

So what next? Heart rate monitors, cortisol levels testing for stress, sensors to measure hand gestures, live-time words sentiment analysis?

They’re certainly options. But not ready yet, and certainly not at the cost of losing the art of presentations as well. Science has its place in communication, but as with most things in life, it is about finding the right balance.

The 100th Monkey is a coaching, skills and communications company which prides itself in its personability, ingenuity and results. We run a ‘Presenting with Impact’ training course, which features everything mentioned in this blog (and much more), in a one-day virtual offering. If you are interested keep an eye out on our courses and events calendar.

- Image credits:

- 100th Monkey team (1)

- 100th Monkey team (2)

- 100th Monkey team (3)

- 100th Monkey team (4)