The Uncertainty Principle: why campaigns perform the way they do

Michael Paul offers an introduction to the Uncertainty Principle and how it impacts campaigns.

Humans hate uncertainty.

Presumably it’s an evolutionary trait: pursuing certainty over risk improved chances of survival, with Darwin doing the rest. However, our aversion to uncertainty undermines understanding of communications and its potential impact.

Solving this starts with acceptance.

We must accept that uncertainty is hardwired into the landscape of human behaviour, and that’s fine.

The predictability paradox

Humans are both predictable and unpredictable.

Social pressure, frequency bias and choice paralysis – examples of heuristics – help us predict reactions to situations and shape communications. But understanding the role, strength and mix of heuristics at any given point is incredibly difficult, if not impossible.

This is because an unknowable number and variety of internal and external factors shape our attitudes and behaviour.

We can now create a formula describing campaign performance:

Campaign performance is the result of an unknowable range and variety of positive and negative, internal and external factors that impact human behaviour.

As an example:

Performance = brand ± media budget ± audience reached ± creative strength ± weather ± economy ± lighting conditions ± level of hunger and so on.

I find that accepting this unknowable equation will give me my outcome puts me in my place as a communications professional, and gives me a much more realistic mindset on the potential impact of any campaign I work on.

Mental availability

If campaign performance is largely out of our hands, why do campaigns work?

Communication is an external force exerted on human behaviour. The key is understanding what that force is. The best existing answer to this is in Professor Byron Sharpe’s How Brands Grow, which draws on the ideas of mental and physical availability. Here we’ll focus on the former.

Mental availability is the probability of an individual noticing, recognising or thinking about their brand at the point a decision is made. Sharpe’s work is commercial, but it applies to government communications, too: for example, increasing the probability that somebody thinks about teaching as a potential career at the point that person is considering future life options.

In COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour), this is equivalent to strengthening people’s motivation and perceived self-efficacy: “I know what to do and how to do it.”

Sharpe outlines a few ways we can improve our campaign’s mental availability, which I have found to work in practice.

The first is reach. One day somebody is receptive to what you’re saying, the other they’re not. You therefore need to reach as many people in your audience as possible to ensure you take this into account.

How do I do this?

There are lots of ways to practically do this, depending on your constraints, but the question “does it increase reach against our target audience” should be one of the first questions you ask (thanks again, Sharpe).

The second is brand codes. These are the symbols and associations that people link to your brand or campaign. If used, your awareness and recognition will increase. These include how things look, which is important, as well as messaging, tone, and the general signal you wish to transmit. It should be applied consistently over time and to everything from your TV advertising to the buttons on your website and call centres.

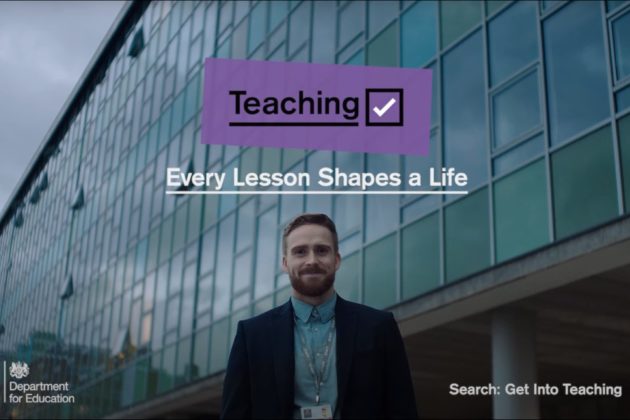

For example, there are physical and conceptual codes associated with teaching: staffrooms and the impact a teacher has on students. We use these in the teacher recruitment campaign at the Department for Education (DfE).

How can I apply the idea of brand codes to my communications planning? A useful question to ask yourself is this: if I removed the brand or campaign name from this piece of communication, would people know who it was from?

Context and campaigning

Remember, communications is just one element of campaign performance, and a change in context could completely change the fortunes of your campaign. From heatwaves to pandemics, there is no end to the list of unpredictable factors that could affect your audience’s behaviour.

What I’m trying to say is this: Do what you can, but be realistic with what you can do. Embrace the uncertainty and set yourself free.

Michael’s Comms Exchange, 3 February 2021 (GCS members only, ask the development adviser in your department for the password)

- Image credit:

- Department for Education (1)