PITCH: Strategic communication as a tool of global influence

The challenge

“The most significant lesson of the last two years is not just that the world is a more dangerous place, but that when challenged we are ready and able to respond, working quickly and effectively with our partners.

As the global context evolves further, systemic competition continues to intensify and new challenges emerge, we must make sure that this remains the case by taking a lead where we can make the most difference and finding new ways to cooperate with others to maximise our collective impact.”

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, Integrated Review Refresh 2023

Introduction

The global information ecosystem is changing fast. In an increasingly interconnected world, communication is effectively borderless. Digital newspapers are read around the world and social media posts do not respect national boundaries. While technological innovation continues to bring new opportunities which can be harnessed for the public good, it also contributes to the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

Our competitors are leveraging existing and emerging capabilities in information manipulation to undermine global cooperation and weaken support for liberal democracy. Both Russia and China invest heavily in global cultural power projection and information operations. Information is central to Russia’s war on Ukraine, and the Russian tradition of deception has deep roots. Soviet textbooks on psychological operations taught students that, in defending the state, “a lie is not a lie, but a weapon”. In the last 12 months, we have seen the extent of Russia’s global weaponisation of information to deny responsibility for its illegal invasion of Ukraine. Its disinformation campaigns are systematic, well-resourced, and perpetrated on an industrial scale.

Yet truth powerfully told remains an essential tool in countering our adversaries and responding to the hostile manipulation of information. We can still harness the power of effective communication to shape the global information environment.

In the recently published Integrated Review Refresh, the UK committed to further developing our information statecraft capabilities, building on the success of these in constraining Russia’s room for manoeuvre in Ukraine. Information statecraft is no longer simply a matter of state-to-state diplomacy or even state-led public diplomacy, but requires seizing the communications potential of the digital age in order to challenge disinformation and promote truthful narratives. In doing so, we will protect and promote our interests and play an active role in defence of openness, freedom and the rule of law.

This document provides a single source where those working in international communications can find the key doctrines that underpin the UK’s approach to public service communication. It builds on a decade of Government Communication Service (GCS) best practice and the latest learnings from the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and Ministry of Defence as a consequence of the Russia-Ukraine war.

This is also an area where the UK has a comparative advantage. From the professionalism of our diplomats and the creativity of the internationally acclaimed GREAT campaign, to the UK’s leadership of the Global Coalition Against Daesh’s communications and the high regard in which our military is held, the UK’s international reputation for effective communications enables us to be listened to and convene allies in a way that others envy.

We are therefore using the opportunity of the Integrated Review Refresh to bring together the best strategic communications techniques and practices to support the UK Government network in their delivery of first-class information statecraft.

Executive summary: The PITCH

- Modern communication is borderless and vital to shaping perceptions and influencing the actions of states, organisations and individuals – from people deciding which country to visit on holiday, to governments deciding who to align with for UN votes.

- Our adversaries are investing in communication capabilities to change the global order, which has served us well and led to both peace and prosperity since 1945.

- The UK uses diplomatic influence, economic and soft power, and when necessary military force to achieve its international goals. Effective strategic communication runs through these levers of statecraft. If the UK is to be successful, it needs to fully use its communication capabilities in terms of allies, assets and abilities.

- Truth told powerfully, consistently and creatively can deliver tangible benefit to our democracy, international standing, trade and tourism. The GREAT campaign, which has delivered £4 billion of additional economic benefit over a decade, is testament to this fact as a successful cross-government, multidisciplinary campaign.

- Strategic communication is the end-to-end planning and systematic approach to applying the full range of communication tools to achieve an outcome almost always aimed at perception or behaviour change. Communication strategies aim to protect our national interests for maximum effect and engage globally to influence people in line with our values.

- The PITCH approach summarises how we can deliver effective global communication campaigns. These need to be done in partnership, based on audience insight and with robust evaluation, using trusted voices to deliver compelling and credible content. Most importantly, the approach must be honest and delivered in line with our democratic values.

- Success requires all those involved in government communication to work together to agreed goals, sharing research and campaign outcomes and abiding by agreed professional standards. In a crowded and contested global media environment, the highest levels of discipline and professional practice are required for our communications to succeed.

- While the RESIST 2 framework sets out how organisations can effectively identify, monitor and build resilience to disinformation, the PITCH toolkit focuses on the opportunities for proactive communications with international audiences. It builds on the ‘Strategic communications’ step of RESIST, bringing together best practices and case studies for developing and implementing international communication strategies. Crucially, our model is based on the principles of honesty and integrity. We simply put forward the truth, well told.

Background

About the modern information environment

Recent growth in technological innovation and the increasingly borderless and digitised media landscape have meant that the information sphere has become an arena of intensifying geopolitical competition.

“Information is more important to world affairs today than at any previous point in history as a result of recent advances in data-driven technologies. These advances have revolutionized each of the four key facets of information power: to influence the political and economic environment of other actors; to create economic growth and wealth; to enable a decision-making edge over competitors; and to communicate quickly and securely.”

Eric Rosenbach and Katherine Mansted, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School (May 2019)

“We are responding to the ever-evolving ways in which authoritarians seek to subvert the global order, notably by weaponizing information to undermine democracies and polarise societies. We are doing so by working with governments, civil society, independent media, and the private sector to prevent credible information from being crowded out, exposing disinformation campaigns, and strengthening the integrity of the media environment – a bedrock of thriving democracies.”

US Government National Security Strategy (October 2022)

“There is strong evidence pointing to Russia as the primary source of disinformation in Europe. Disinformation is part of Russian military doctrine and its strategy to divide and weaken the west. Russia spends €1.1 billion a year on pro-Kremlin media. You will also have heard of the ‘troll factory’ based in St Petersburg and the bot armies.”

Andrus Ansip, Vice-President of the European Commission (December 2018)

“Chinese propagandists have studied Russian techniques of flooding the information space with false narratives and wish to emulate Russian success in influencing U.S. actions and sentiment. A concept in Chinese political discourse called huayu chizi references a deep seated feeling that China is maligned or, worse, ignored during global discussion and debate. The remedy to this is strengthening its own wai xuan, or external messaging (propaganda) to spread the PRC message in a positive light.”

Christopher H. Chin, Nicholas P. Schaeffer, Christopher J. Parker, and Joseph O. Janke, Joint Force Quarterly 109 (April 2023)

“But it is Zelenskyy’s never-ending communications that have been most remarkable. His nightly video messages and Telegram posts have been a tonic for a weary population. A message directed at Moscow in September – “Without light or without you? Without you” – turned into a social media rallying cry for many Ukrainians. Zelenskyy has addressed countless parliaments, conferences and events – from the Grammy Awards to the Glastonbury Festival. Each time he has tailored the message to the audience, often appealing to the hearts and minds of the people over their governments. He has used his pulpit to press – and sometimes shame – governments into providing vast quantities of weapons.”

Roula Khalaf, Christopher Miller and Ben Hall, Financial Times (December 2022)

What is information statecraft?

Statecraft is the art of synchronising ends, ways and means to achieve national goals. Information statecraft is the application of a communication strategy to create the conditions to advance national goals by successfully shaping the information environment and public perception.

The 2017 US National Security Strategy arguably popularised the term information statecraft. The strategy outlined the risks posed by and the need to respond to the weaponisation of information by competitors, including through “…coherent communications campaigns to advance American influence…”.

The UK’s 2023 Integrated Review Refresh has since highlighted “the hostile manipulation of information by actors including Russia, China and Iran” and the need to strengthen our information statecraft in response. This means assessing and responding to mis- and disinformation, as well as raising overall strategic communications capability. This paper addresses the commitment in the 2023 Integrated Review to “develop our broader deterrence and defence toolkit, including information operations and offensive cyber tools, and make greater use of open source information alongside our intelligence capabilities” and “strengthen our economic capabilities, and information statecraft, building on the success of these tools in constraining Russia’s room for manoeuvre in Ukraine”.

It is important to note that information statecraft is one element of the UK’s broader strategic approach to countering state threats, which encompasses military instruments as well as economic capabilities such as sanctions, as part of an integrated approach to deterrence and defence.

The purpose of this toolkit

Why do we need PITCH and who is it for?

As part of the UK’s approach to information statecraft, we are using the best government strategic communication tools and adapting them for international engagement.

PITCH shows how to use partnerships, insight, trusted voices, compelling content and honesty to tell our story well and truthfully, shape the information environment and achieve policy objectives.

This toolkit is primarily for UK Government officials responsible for international communications, including officials and diplomats representing the UK overseas. It sets out the core components of a strategic communications approach for international audiences, combining traditional and innovative channels and tactics.

The toolkit aims to be accessible as an introduction for those who are new to the field of strategic communications. For those who are more experienced, it brings together best practice techniques that will build on existing expertise and act as a helpful reference point for communications planning.

With it, communications should be used more proactively and more confidently to promote the UK’s values and interests globally, and to contest the disinformation propagated by our adversaries.

When should we use PITCH?

The OASIS framework (Objectives, Audience insight, Strategy/idea, Implementation, Scoring/evaluation) is used by government communicators to plan any communications and campaigns. It provides a series of steps to develop your plan and structure your thinking.

PITCH is best used at the ‘Strategy’ and ‘Implementation’ stages to explore communication tactics. See Annex B for more information on OASIS and other core UK Government communication tools.

How to PITCH your campaign

PITCH is a best practice campaign guide for designing and delivering effective communications in a contested international information environment.

Partners and allies: The foundation and licence to operate

- Internal partners are crucial. Communications must be fully integrated with policy and diplomatic and operational activity to be effective.

- Monitor and evaluate continuously, adjusting your approach accordingly. This means investing in a dashboard into which you can pull sources of data to assess the reach and impact of your communications and adjust accordingly.

- Use the power of networks to deepen relationships with allies and partners. Share information, best practice and capability building – particularly important for countries under pressure from disinformation.

Insight: Understanding the possibilities and limitations of the communications approach

- Build a rich understanding of target audiences using research and local knowledge from trusted sources.

- Ensure the economic, social, cultural and political complexities of the local and regional context are well understood, including the risks posed to audiences by misinformation and disinformation.

- Use this insight to inform the approach (message, audience and timing) of your communications strategy.

Trusted voices: Building a campaign into a community and a movement for change

- Building a network of trusted voices means taking a whole of society approach. Collaborate with and mobilise a community of third-party voices to increase the credibility and reach of activity. Ideally, the campaign should develop into an alliance of willing partners and the alliance into a community who can see benefit from achieving the public service goals we pursue.

- To quote the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023: “Audiences say they pay more attention to celebrities, influencers, and social media personalities than journalists in networks like TikTok, Instagram and SnapChat”. This generational change argues for a particular focus on credible people and organisations who we can build mutually beneficial alliances with and who will help us make our case. These may be businesspeople, community leaders, academics, experts or politicians. And both parties should be clear and transparent about what we are seeking to achieve.

Compelling content: Making the argument memorable

- In a multimedia, technicolour and digital world, picture and video are more powerful than a script or press release. That means every initiative needs striking visuals and a credible story, based on a few strong proof points that align to target audience values and interests. The most successful modern communicators tell stories rather than reading scripts or narratives. A story has characters, a plot, setting conflict and resolution. It is not a narrative in terms of a justification for a particular course of action.

- Make use of multiple channels to deliver a regular flow of activity. Consider a mix of traditional diplomatic engagement and media relations, as well as digital (owned and earned) channels that are relevant to audiences. We should use the full range of communication channels from direct communication to the latest digital platforms and the opportunities that online environments, such as gaming, present in terms of placing messages.

- Communicators must maintain a broad awareness of the technological advances and implications for communications, as part of an active consideration of emerging opportunities for innovation – both radical and incremental.

Honesty and integrity: Communicating authentically and building trust

- Transparency and credibility must be at the heart of communications, upholding our core democratic values. Truth is always the strongest argument and beats any attempt at covert and overt manipulation.

- Trust is established through delivering on what we promise and demonstrating our credibility. This is the essential foundation for communication.

- Similarly the Civil Service Code and its requirement to honesty, integrity, impartiality and objectivity and the GCS proprietary guidance provide essential rules for delivering communication.

- There are occasions when information statecraft does require discrete or covert activity. Everyone involved in these operations understands the need to operate on a lawful basis and with appropriate authorisation and clear justification, for example to prevent loss of life or to reach audiences who would not be able to directly receive information from the UK Government.

Partners and allies

“Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.”

Helen Keller

Internal partners

Communication is one of the main levers of change that the UK Government uses to realise its objectives and implement public policy, alongside legislation, regulation and taxation. To be effective, international communications must work in partnership with wider soft and sharp power assets.

By integrating communications planning and delivery with policy, diplomatic activity and operational activity, we can deliver coordinated and cohesive campaigns – crucially, avoiding a ‘say/do’ gap and ensuring that our communications are in line with the latest policy decisions and activity on the ground.

Getting the fundamentals right is key. It starts with being clear about shared policy and operational goals which communications can inform, shape and help execute.

As outlined in the ‘Objectives’ step of the OASIS framework, communicators must firstly understand the policy aim and then develop communications objectives that will contribute to achieving this. Objectives for international communications are generally focused on economic benefit (for example, intention to visit or invest in the UK) or changing perceptions (for example, favourability towards the UK).

When setting objectives, consider how you can work with internal partners to continuously monitor and measure the impact of your communications. Use digital analytics, media monitoring, operational data and, where budgets allow, research and polling to assess progress against your objectives. Reflect on the learnings, iterate and adapt your approach as needed, responding rapidly to any changes in the operational environment.

Internal communications are also integral to success by aligning cross-government stakeholders on how best to engage and communicate with audiences. Ensure messaging is clear, consistent and shared with all relevant teams. The need for an aligned, disciplined and whole of government approach is particularly important in the context of the dramatic increase in disinformation driven by digital technology and the potential for any inconsistencies in our own communications to be exploited by adversaries.

Case study: Carrier Strike Group 2021

Carrier Strike Group 21 (CSG21) saw the aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth lead a multi-national flotilla of ships and aircraft on a nine-month voyage from the Eastern Atlantic to the Philippine Sea and back again. Alongside COP26 in Glasgow and the G7 Summit in Cornwall, it was one of the UK’s set piece foreign policy events of 2021.

At the sharp end of operations, CSG21 included major NATO exercises in Europe, coalition air operations against Daesh in the Middle East and a freedom of navigation passage through the contested waters of the South China Sea. But CSG21 was as much about diplomacy as it was about defence, with the ships of the Carrier Strike Group engaging and exercising with more than 40 countries, hosting presidents and prime ministers and providing a backdrop for embassy and high commission-led events designed to promote bi-lateral trade and co-operation.

The creation of a dedicated CSG21 Policy and Communications Unit in the Ministry of Defence exemplified a multidisciplinary approach, co-ordinating plans across government and the Diplomatic Service, with participating international partners.

The nine-month deployment was broken down into six distinct phases, each with its own communications plan, tailored messaging and a live grid of activities and engagements. A regular drumbeat of situation reports from the Carrier Strike Group back home ensured that all participating organisations were kept informed, while close cooperation with embassies and high commissions saw tweets translated into Hindi, Arabic, French, Thai, Malay, and Japanese – a relatively simple undertaking that achieved considerable reach.

Through a series of well executed media serials, CSGS21 served to launch the UK’s ‘tilt’ to the Indo-Pacific. This has now developed to include the AUKUS agreement with Australia and the United States, a partnership to develop a fighter jet with Japan and Italy, and the UK’s accession to the Trans-Pacific Partnership. With the Carrier Strike Group due to return to the region in 2025, CSG21 has affirmed the benefits of aligning the economic, diplomatic and military strands of the UK’s strategic messaging in the region.

The power of allies

In a world where disinformation is spreading, investment in networks pays off. Working with our allies enables rapid information sharing and message amplification, and provides a coherent counternarrative. By speaking with a common voice, we can most effectively combat the spread of false narratives and build support for democratic values.

Bilateral engagement is a mainstay of our relations with nations around the world – ambassadors, defence attachés, UK Government ministers and officials frequently hold talks with their counterparts in partner countries. These meetings offer communicators a valuable hook for proactive press and social media activity, helping to show visible progress and co-operation between the UK and partner countries on shared issues and challenges.

Multilateral organisations also provide a unique platform to influence and put forward our own narrative. They enable the UK to speak directly to policy makers and diplomats from across the world, as well as directly to the public via the often wide international media presence. Alongside traditional media relations tools (such as background briefings, interviews, statements and press releases), communicators should maximise these opportunities by considering more proactive and creative communication tactics, such as events or showcases, and innovative digital content, which can be delivered in the sidelines of multilateral fora and events.

As well as leveraging traditional diplomatic engagement methods, communicators should build their own powerful networks with fellow practitioners in partner countries, sharing communications best practice and capability building. This is particularly important for countries under pressure from disinformation.

Case study: Russia-Ukraine war

Established in 2022, the UK Government Information Cell brought together a cross-government team of professionals in assessment and analysis, counter-disinformation and strategic communication, working with our NATO, EU and Five Eyes allies to identify and expose Russian disinformation.

Through these active networks of working-level partners, we were able to rapidly coordinate a shared view of the situation and develop joint approaches.

We also declassified intelligence information, exposing Russia’s propaganda and deception. When Russia attempted to legitimise its illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory through sham referenda, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office worked with partners to ensure Ukrainian civilian voices were able to speak out against Russian attempts at the UN. The Foreign Secretary’s speech at the September 2022 UN Security Council pre-bunked the upcoming sham referenda, including Russian plans to fabricate the outcome, and contained direct witness testimony of the horrific treatment of civilians by Russian forces in Bucha.

We also held regular conference calls with allied government communicators, up to 150 people at a time, providing reassurance to them from the expertise, situational awareness and campaign ideas that the UK government was able to offer.

Participation in the NATO senior communicators conference, study visits to Washington DC and our annual hosting of the EU seminar on strategic communication provided areas for partners and allies to gather, exchange views, increase their knowledge and agree on areas to work together.

Case study: European Political Community Summit, Chișinău, Moldova

1 June 2023 was a big day for Moldova, which hosted the second ever meeting of the European Political Community. Only 12 miles from the country’s border with Ukraine, 49 European leaders, including the UK Prime Minister and Ukrainian President, met to discuss European security and unity.

Drawing on their international communications expertise and experience, a team of UK Government communicators from the Cabinet Office was sent to the country to support the government of Moldova in their international communications, media coordination, and on-site operations.

With over 800 journalists and broadcasters from around the world, plus all the demands of an international summit, the UK team helped our Moldovan counterparts pull off a successful event in the world’s spotlight. The summit earned 4,946 international media articles, successfully showcasing Moldova’s European values and ambitions against an increasingly hostile Russia seeking to destabilise the country and its neighbours.

Key takeaways

– Be clear about shared policy and operational goals which communications can inform, shape and help execute.

– Integrate your communications delivery with policy, diplomatic activity and operational activity, ensuring message discipline and consistency.

– Continuously monitor and reflect on the learnings and impact of your communications. Respond rapidly to any changes in the operational environment.

– Build networks of contacts in partner governments, sharing best practice and exploring how to co-deliver messages for maximum effect.

Insight

“Every act of communication is a miracle of translation.”

Ken Liu

Thinking about the audience and how to understand them

As set out in the OASIS framework, a communications strategy should always be based on a clear understanding of the target audience and the context for our communications, recognising the diversity of opinion and lived experience among different audience groups. What are their motivators, drivers, beliefs and interests? What are their trusted sources of information and how do they consume news? What is the level of risk posed by misinformation and disinformation? By finding out more about audiences’ behaviours, intentions, attitudes and communication preferences, insight can help to make sure any communications are as relevant, meaningful and impactful as possible.

There is a significant amount of publicly available information about almost any target audience. A review of existing audience data and insight, including quantitative and qualitative research on attitudes, beliefs and habits, is therefore an essential first step for any communicator. A second step is to leverage the local knowledge and insights of internal stakeholders, partner governments and civil society organisations. Only when these two routes are exhausted should you seek to commission new primary audience research (in terms of paying for opinion polling, for example).

Once you have built a rounded and clearly defined picture of your target audience, use this insight to inform the following core elements of your communications strategy:

- Resources – consider the size and spread of your target audience within the context of your available budget and resources. You may need to prioritise specific audience segments.

- Channel strategy – select channels and platforms that are trusted by your target audience and where they will be most receptive to your messages.

- Messaging – ensure the tone and content of your message will resonate with your audience.

Case study: The Counter-Daesh Communications Cell

The Global Coalition Against Daesh is a unified body of 86 international partners, dedicated to the enduring defeat of Daesh. The UK leads the Coalition’s work to counter Daesh’s propaganda and build community resilience to Daesh’s influence through the Counter-Daesh Communications Cell (CDCC).

Understanding the Syrian and Iraqi audiences vulnerable to Daesh’s propaganda is fundamental to setting the CDCC’s communications strategy. For example, CDCC’s insight shows that while men play the main role in Daesh operations, women perform critical enabling functions, including in the promotion of Daesh. At the same time, the CDCC’s audience insight showed a gender imbalance in those who viewed and engaged with the cell’s campaigns – with around 75% being men and 25% being women.

The CDCC’s campaigns needed to adjust and be more gender conscious in order to have a greater effect on Daesh women as well as men. The CDCC has therefore made women more prevalent in its content, while continually looking to better understand their role supporting Daesh cells across Iraq and Syria. Furthermore, the cell has broadened the thematic repertoire of its communications to include topics on culture and livelihoods that achieve greater cut-through with female audiences. Recent content has included interviews with female recruits to the Iraqi Security Forces, promoting greater inclusion within the Iraqi security system and supporting its ability to more effectively interdict female Daesh supporter networks. Additionally, CDCC’s audiences are more likely to trust communications from recognisably Iraqi and Syrian voices. Authentic content reflecting the audiences’ lived experiences from voices they trust has helped to build an audience rapport, and is critical to achieving reach and impact.

Dealing with attempts to mislead and divide communities through disinformation

A key aspect of modern information statecraft is tackling disinformation. GCS International has developed a three-step research approach to understanding audience and information vulnerabilities. First, identify which audience segments are vulnerable to misinformation and disinformation. Then analyse the information environment that vulnerable segments are exposed to. Finally, investigate which misinformation and disinformation narratives these audience segments are most likely to encounter.

Information vulnerability mapping

- Susceptibility assessment: Understanding the susceptibility of different audience segments to misinformation is important to inform the targeting of strategic communications. Academics have developed a number of different approaches and methodologies to understand susceptibility such as the Misinformation Susceptibility Test and the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire.

- Media diet analysis: Understanding the information environment inhabited by audience segments that are vulnerable to misinformation and disinformation allows us to develop strategic communications tailored to their style of news and media consumption. What platforms, channels and outlets do they use to consume news and trust?

- Narrative map: Understanding the thematic misinformation and disinformation narratives that vulnerable audience segments are likely to be exposed to ensures that we are tackling the most prevalent narratives; for example, misinformation and disinformation around the COVID-19 vaccine or democratic processes. For this to be successful, it requires detailed contextual understanding.

Close monitoring of the information environment enables communicators to decide which elements of disinformation are genuinely damaging and require action. For example, the monitoring of RT during the early stages of the pandemic and the Salisbury poisoning crisis in 2018 showed that the channel had very limited cut-through in the UK. RT’s promotion of 35 different conspiracy theories as to how the Salisbury poisonings took place reached a tiny audience and were seen by those who did notice them as laughable. The UK Government open letter from the then National Security Advisor to the Secretary General of NATO, setting out the evidence on why the Russian government was responsible for the poisoning, generated far greater coverage, credibility and impact than the state broadcaster.

The UK’s approach to tackling disinformation is regarded as world leading. The RESIST 2 toolkit enables communicators to develop a response that can be used when dealing with all types of manipulated, false and misleading information. Its aim is to reduce the impact of false, misleading, and manipulated information on UK society and our national interests, in line with democratic values.

- Recognise: understand and spot false and misleading information

- Early warning: learn how to monitor the information environment

- Situational insight: transform monitoring data into action

- Impact analysis: assess the impact and threat of false and misleading information

- Strategic communications: discover how to implement communication strategies

- Tracking effectiveness: evaluate the impact of strategic communications

PITCH builds on the ‘Strategic communications’ element of the RESIST framework. The best way of tackling disinformation is by telling a credible and inspiring story about what we are trying to achieve. Alongside independent media such as the BBC World Service and global institutions like the Premier League, the Royal Family and the English language, government communicators have powerful tools that help tell that story internationally. We also have specific tools to tackle disinformation and these should be used as part of our communication strategy.

Key takeaways

– Gather insight to build a rounded and clearly defined picture of your target audience and the local context. Then use this to inform your channel strategy, messaging and resourcing.

– Understand your audience’s vulnerability to misinformation and disinformation using the information vulnerability mapping approach.

– Develop a strong counter-disinformation strategy using the RESIST 2 principles, focusing on areas where actual harm is likely to be done.

Trusted voices

“The two words ‘information’ and ‘communication’ are often used interchangeably, but they signify quite different things. Information is giving out; communication is getting through.”

Sydney J. Harris

In an environment of scepticism and changing levels of trust in governments, we should make our case based on the facts and through organisations and people who are most trusted in each particular scenario. This may be ministers or senior officials, but increasingly, we need to look to external voices across all areas of society to ensure the success of our communications.

This requires regular engagement with credible third-party voices that can reach and change minds among our target audiences – from journalists, experts and non-governmental organisations, to civil society, social media influencers and celebrities. These stakeholders and influencers can offer a highly effective way of reaching audiences, especially those that do not engage with traditional media channels and often have low trust in formal government communications.

Case study: Shared Values campaign

Over the past year, GCS International has worked with partners to co-deliver 11 communications campaigns based on UK frameworks and approaches across a number of UK government priorities, such as maintaining international support for Ukraine and strengthening democratic values.

An example of a multi-country communications campaign is Shared Values – a counter-brand campaign that promotes positive messages about the enduring strength and global leadership of our democracies, and the values we share. It aims to enhance societal resilience to hostile state narratives by making real the individual and societal benefits of democracy, increasing positive engagement with democratic behaviours and highlighting individual responsibility to safeguard them. The campaign is co-developed, co-owned and co-implemented by 14 partner governments.

Over the past two years, Shared Values has now expanded to include a mixture of government and international non-governmental organisations, who share and promote a collective message on democracy and our shared values to audiences around the world. In total, the campaign has now reached over 85 million people organically across 165 countries, primarily through partner networks and channels.

Identifying the influencers

A mapping exercise can be a useful tool to understand the stakeholder landscape and identify the most appropriate influencers for your campaign. Typically, they can be split into sectors covering politics, business, community and culture. We should not be limited by traditional understanding of who is influential. As the Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023 shows, a modern source of societal influence looks very different. Societies have moved from being generally differential to seeking reference points to understand arguments.

Then, consider how to best prioritise your identified influencers. Which individuals or groups are most likely to be able to reach the target audience (based on their prominence in the media or the volume and quality of content and followers on digital channels)? What is their relevance to and level of interest in the campaign subject matter? Remember, authenticity is key to be able to effectively convey campaign messages.

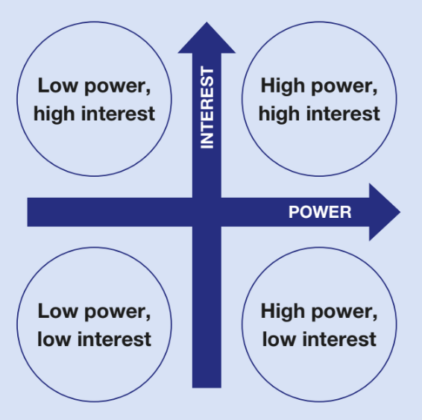

The Boston Matrix

The Boston Matrix is an analysis tool which can help you to identify and prioritise stakeholders.

As with any government communication, it is paramount that the content produced is trustworthy, accessible and represents value for money for the taxpayer. If used in a transparent way, influencers can create personalised and engaging content for your campaign. However, if done incorrectly, public confidence in government communications may be eroded.

Case study: GREAT Love campaign

The GREAT Love campaign was relaunched at Sydney World Pride in 2023 to showcase the UK’s warm welcome, celebrate our values of inclusivity, diversity and freedom, and encourage the world to visit, study and invest in the UK.

Recognising the importance of speaking authentically, the campaign centred on LGBTQIA+ storytellers and gave a platform to a breadth of people from the community. These influencers were encouraged to share their stories, focusing on the objects that they felt represented a pivotal moment in their lives, when they felt included and when they recognised that being part of the community was, in fact, a superpower.

The campaign reached over 5 million people in Australia, driving significant positive perception shifts and successfully encouraging audiences to consider visiting, studying and investing in the UK. Influencer content promoted from their own channels delivered particularly strong engagement, demonstrating the power of influencers in reaching audiences and creating content that resonates. GREAT Love is now being rolled out across the globe and has since featured at Pride events in New York, Miami, São Paulo, Rome, Paris, Beijing, Washington DC, and many others.

Key takeaways

-Any credible campaign will need third-party supporters who are prepared to advocate for our position, based on a transparent understanding of what we are trying to achieve.

-Consider which credible third parties could help you to (more) effectively land your key messages. The choice of a trusted voice will depend on the goals, subject matter and target audience of the campaign.

-Set out your approach to key stakeholders at briefing events. In an era where everyone is a potential producer of content through social media platforms, briefing and explaining is an important communication skill to shape the environment and help generate understanding.

Compelling content

“Content is King.”

Bill Gates

‘Content is King’ is the title of a 1996 essay by Microsoft founder Bill Gates, in which he describes the future of the internet as “a marketplace for content”. That has been proved largely correct.

Content continues to be fundamental to successful modern communication, and producing valuable, relevant content that audiences will respond to should be the bedrock of any campaign. Telling a credible and inspiring story about what we are trying to achieve is particularly important in counteracting disinformation.

Firstly, we need a coherent narrative or messaging matrix that can drive consistency across communication products and ensure alignment with the campaign’s objectives. This narrative must be developed using audience insight, so it has the right voice, tone and vocabulary.

Emotions play a critical role in decision-making and behaviour, so messaging that strikes an emotional chord can be effective. Clarity and brevity are also key. In ‘Brutal Simplicity of Thought’, Maurice Saatchi argues that effective communication requires a “deep distaste for waffle vagueness platitudes and flim flam” and the “painful necessity of thought” to create the simplicity and directness which “clarifies and strengthens a cause that is strong”.

But we also need to consider the power of visual storytelling. Humans respond to and process visual data incredibly quickly. According to Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientists, the human brain can process an image in just 13 milliseconds. Any narrative should be capable of being boiled down to three words, a picture or image, a tweet and a paragraph.

“A campaign is a planned sequence of communication that makes use of all appropriate channels to achieve defined outcomes in a specific time frame by influencing the decision makers who will allow success.”

Alan Barnard, ‘Campaign It!’

Content must then be placed in the right channels to be effective. In today’s highly competitive information sphere, we need to inspire our audiences with compelling, engaging content across multiple channels to ensure our communications have the cut-through required. We should be alert to a greater preference among the general public towards online and peer-to-peer video-led channels.

For example, the Foreign Secretary’s visit to Japan in April 2023 ahead of the G7 Summit was immortalised with a manga animation. This creative, digital approach delivered excellent reach, being seen more than 100,000 times across social media and receiving coverage in domestic and international press. Most importantly, it also enabled the effective delivery of the Foreign Secretary’s key message of the importance of “a free and open Indo-Pacific”.

Similarly, during the deployment of the Carrier Strike Group 21, most news coverage was driven by imagery, with relatively few traditional press notices. By far the most important capability was the presence of three of three Royal Navy photographers within the Carrier Strike Group, supported by a video editor and graphic artist back in the UK. This enabled rapid spread of pictures and videos via social media to a worldwide audience.

Case study: Cricket diplomacy

2022 was a standout year for UK-Pakistan sporting and cultural ties, coinciding with the 75-year anniversary of UK-Pakistan relations, the Birmingham Commonwealth Games, the England T20 Pakistan cricket tour and the World Cup T20 England-Pakistan final.

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s UK Pakistan Network made full use of this opportunity by creating compelling video content, as part of their wider EkSaath4Cricket (Together4Cricket) campaign. Led by the High Commissioner, the video series included an interview with the English cricket team captain, Jos Buttler. Content was delivered in Urdu and carried clear messages on the UK and Pakistan’s partnership as the nation marked 75 years of independence. Most importantly, it was relevant to local audiences by tapping into a love and passion for cricket.

The video series reached more than 1.5 million social media users in 24 countries, earning over 500,000 views. The #UKsePK hashtag made it into the top five social media trends throughout the tour in Pakistan and this video content was then picked up by politicians (Foreign Minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari), senior TV sports journalists (Aalia Rasheed and Zainab Abbas), as well as influencers (former international players Shoaib Akhtar and Sana Mir).

The content was carried at prime TV slots and led to eight interviews across TV and print channels, amplifying the reach of core messages, including the UK’s commitment to Pakistan. Oxford Professor of Global History and author of ‘The Silk Roads: A New History of the World’, Peter Frankopan, described it as “not just exemplary 21st century #Diplomacy – outstanding full stop”.

When designing content as part of an international strategic communications plan, consider the 3 Vs – visual, volume and value-driven.

- Visual

- Prioritise visual, easy to digest information and content. The key takeaway needs to be legible, without policy jargon, and immediately demand attention.

- Develop a variety of content that will appeal to your target audiences and is suitable for different platforms and contexts – but be consistent on specific messages and branding (typography, colour and layouts) to help build reputation and recall.

- For digital channels, don’t just fall back on static graphics. Consider disruptive executions that can ‘stop the scroll’. For further guidance on creating and delivering digital content, review the Digital Discipline Operating Model.

- Volume

- Consider the timing and frequency of communication needed in the specific context. The relevance and timeliness of messaging is key to creating influence and working as a motivator.

- Consider relevant wider cultural moments that can be used as ‘hooks’ for core messages.

- In fluid situations that are prone to exploitation of ambiguity, maintaining a high pace of ‘always on’ communications can help to establish trusted voices, maintain engagement, and counter adversaries’ attempts to manipulate narratives.

- Value-driven

- Our values are our best asset in many cases; promoting what the UK stands for, along with the best aspects of our society, is a powerful proposition in attracting, persuading and influencing international audiences. From culture, education and sport, to the UK’s thought leadership and core democratic values, a communicator’s job is to find ways to translate these assets into greater influence for the UK on the international stage. Ukraine’s president, government and people have shown us the benefits of building a united purpose based on values.

- As highlighted in the Integrated Review Refresh, it is also important to recognise that not everyone’s values or interests consistently align with our own. We must understand our audiences and the areas where our values and interests align in order to make the most compelling case. Show the mutual benefit of working with the UK and the impact that we can have together on the issues that our audiences care about. Wider geo-political statements can lose their impact at the regional and local level, so anchor in local programmes and development where possible.

Case study: Foreign Secretary visit to the Philippines

An insight-led, hyper-targeted video helped to make real the UK Government’s commitment to a free and open Indo-Pacific, as part of the Foreign Secretary’s visit to the Philippines in August 2023.

Aligning with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office’s Indo-Pacific communications strategy to use tactical activity in key markets, the team developed a short, engaging video to effectively communicate the UK’s long-term partnership with the Philippines and support for the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Featuring the Foreign Secretary and the Philippines Coast Guard, the video was posted on British Embassy Manila’s Facebook page amidst news coverage of the Foreign Secretary’s China visit and China’s release of a ‘standard map’ depicting contested waters in the South China Sea as part of their domain.

The video reached 1.8 million people in the region and gained 15,000 likes. This strong engagement and positive sentiment shows the power of effectively matching our message (maritime security) to our market, where the South China Sea is a major concern and UK intervention on the issue was welcomed.

Innovation

Technological innovations provide huge opportunities for government communications. The recent explosive growth in generative AI shows just how fast-paced and transformative technological change can be.

AI technologies can unlock a new era of hyper-personalisation, providing communicators with the ability to rapidly generate individualised messaging, tailored recommendations, and dynamic synthetic content. Such innovations could enable communicators to speak across different cultures and languages at a scale which would have previously been cost prohibitive. However, it could also lead to increasing volume of content and messaging towards individuals, further fuelling the fight for audiences’ attention, and elevating the importance of new approaches towards measuring and optimising creative content and advert placements using attention metrics.

What is AI?

Artificial intelligence (AI) is best understood as a family of technologies which includes the application of large language models, natural language processing, other foundation models and machine learning techniques, to produce tools for specific tasks. Some refer to this as ‘narrow’ AI, which is distinct from ‘general’ AI which has not yet been developed.

More immediately, generative AI can significantly speed up content creation. Within the next 18 months, it is realistic that marketing and communications professionals will increasingly collaborate with generative AI to do tasks such as creating drafts of press releases and generating content to support communications campaigns.

As technology continues to evolve and new innovations emerge, it is crucial to consider how to take advantage of these changes in an ethical and responsible way.

All communicators should maintain a broad awareness of the latest technological advances and communications trends, an understanding of the implications for government, and active consideration of emerging opportunities for innovation. As well as the opportunities presented by radical innovation, it’s important to also consider incremental innovation – this could be exploring new channels, partners and influencers, or conducting an A/B test on social media to identify the most compelling messaging for your audience.

By April 2024, GCS will publish guidance under the Innovation and Data Strategy on the ethical use of new technology, including a new ethical decision-making framework for members to guide adoption. This will be designed to work in concert with the latest guidance from the Central Digital and Data Office on use of generative AI, which should always be compliant with data protection law.

ChatGPT4’s view

When asked how to approach the subject of information statecraft, this is what ChatGPT offered:

“Information statecraft refers to the strategic use of information, misinformation, and disinformation by nation-states to advance their national interests, shape global narratives, influence public opinion, and achieve geopolitical objectives. It encompasses a wide range of tools and tactics, from conventional public diplomacy and strategic communication to covert operations and cyber warfare.

Here’s how it can be successfully used by nation-states:

1. Define clear objectives: The state should first determine its foreign policy and national security objectives. Information operations should align with these objectives.

2. Integrate across platforms: It’s crucial to deliver consistent messages across multiple platforms, from traditional media outlets to social media.

3. Localise messages: Content should be tailored for specific audiences. This might involve translating content into local languages or framing messages in ways that resonate with a particular culture.

4. Use credible sources: Information campaigns are more effective when they come from or are endorsed by credible sources. This could be respected individuals, institutions, or media platforms.

5. Counter disinformation: States need to anticipate and rapidly counter false narratives spread by adversaries. This requires monitoring, fact-checking, and rapid-response capabilities.

6. Protect information infrastructure: A nation should safeguard its information sources and platforms against cyber-attacks and infiltration. This involves strong cyber defences and regular audits.

7. Engage with allies: Collaborating with allies can amplify messages and create a more cohesive narrative on the international stage.

8. Transparency and authenticity: While there’s a place for covert operations in information statecraft, it’s essential to build trust with the global audience. Being caught in blatant lies or manipulations can severely damage a nation’s credibility.

9. Long-term perspective: Information statecraft is not just about immediate results. It’s about shaping perceptions, building relationships, and influencing attitudes over the long term.

10. Adaptability: The information landscape is continuously evolving, with new technologies, platforms, and tactics emerging. States must be flexible and adapt to these changes to remain effective.

In conclusion, while information statecraft can be a powerful tool for nations, it requires a nuanced approach, a clear strategy, and continuous monitoring and adjustment to be effective.”

Considering the GCS professional knowledge that would have informed ChatGPT’s output, its response and the PITCH doctrine are reasonably closely aligned. Our focus on partners is reflected in engage with allies (7) and setting objectives (1). Our insight point is not reflected in the AI answer, while our focus on trusted voices is matched by point (4) on credible sources. Our content argument is reflected in the argument to integrate (2), adaptability (10), counter disinformation (5) and localised messages (3), while honesty is replicated in the chatbot’s views on transparency (8). ChatGPT’s advice on a longer term perspective (9) and protecting information infrastructure (6) are not explicit parts of the PITCH doctrine but do add a helpful perspective to information statecraft. All of this demonstrates the power of emerging technology to help us do our work.

Key takeaways

-Use striking visuals, especially in video form where possible.

Consider the full range of channels available to deliver your messaging – from traditional diplomatic means and media relations, to new digital platforms.

-Ensure your communications are based on strong proof points, anchoring in local programmes and development where possible.

-Test and trial AI and see how it can inform your communication. Use this according to the Civil —Service and GCS guidance and only in areas where it will not suggest changes to government policy or cover sensitive matters.

Honesty and integrity

“If I lose mine honour, I lose myself.”

William Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra

The UK first established a Department for Information in 1917 in order to produce and present more factual and accurate communication about the First World War. We have learned over our history about the importance of explaining, justifying and presenting government information accurately.

As Kenneth Grubb, Controller of the Ministry of Information from 1941 to 1946, wrote: “Information services …are a recognition of a certain maturity in a democracy. They testify to a society where facts are essential to the formation of views, where prejudice is to be combatted by reason and where policies should be explained if they are to be understood”. This belief remains the guiding purpose for UK government communications.

Strategic communications are therefore conducted in a legal and ethical manner, in line with domestic and international law and our democratic values. In the UK, the Civil Service Code and the GCS propriety guidance are the starting point for all government communication activity. The guidance states that government communication should:

- be relevant to government responsibilities

- be objective and explanatory, not biased or polemical

- not be – or liable to be – misrepresented as being party political

- be conducted in an economic and appropriate way

- be able to justify the costs as expenditure of public funds

Above all, democracies should prioritise truthfulness in their communication strategies as we seek to provide accurate and reliable information to the public. Given the rising sophistication of AI-powered deepfakes and the proliferation of misinformation and disinformation, our responsibility to communicate authentically and build trust with our audiences has never been more crucial.

Background briefings and declassification are valuable tools in this endeavour, as the sharing of timely information to back up our assertions can significantly strengthen our hand in the fight against misinformation and disinformation. Thinking on communication and intelligence continues to be influenced and guided by the findings of the Iraq Inquiry, which found: “The widespread perception that the September 2002 dossier overstated the firmness of the evidence about Iraq’s capabilities and intentions in order to influence opinion…has produced a damaging legacy, including undermining trust and confidence in government statements”. The Iraq Inquiry led to fundamental changes, and serves as an important reminder of the need for transparency and an ethical use of secret information, which should inform our approach to communications.

Committing to ethical principles in using information demonstrates a respect for the values that underpin democratic societies. Ideally, this maintains the moral high ground and distinguishes democracies from authoritarian regimes that spread false information and engage in unbridled political warfare without regard for the consequences. George Orwell recognised this and the sanctity of truthful information is central to ‘1984’: “Freedom is the freedom to say that two plus two make four. If that is granted, all else follows.”

Ethical conduct in information statecraft is, therefore, critical to cultivating trust among audiences. This in turn fosters resilience. When governments and their institutions are transparent and accountable they foster trust and credibility, which are essential in maintaining a cohesive society. In times of crisis, this can be the difference between successful navigation of challenges and societal unrest.

Moreover, abiding by ethical standards in information statecraft helps to ensure that actions are more effective and sustainable. We can build and maintain alliances based on shared values and interests. These alliances are invaluable for developing and executing effective strategies to counter our adversaries. By acting on ethical principles, the UK Government can strengthen their moral standing, foster trust, and forge lasting alliances, ultimately ensuring the effectiveness and sustainability of their information operations. The guiding principle for our approach is ‘the truth well told’.

TRUST principles

The following principles, which have been summarised by this toolkit, have been used by national security communicators to guide their work:

Transparency: Information statecraft will be conducted in a legal and ethical manner, in line with domestic and international law and our national values. Democracies must strive to be transparent in their actions.

Respect: Democracies should respect the dignity of individuals and groups. They should avoid using information warfare tactics that manipulate or coerce people.

Usefulness: Democracies should ensure that their information tactics serve a specific purpose, such as promoting awareness of important issues or preventing harm.

Safeguards: Democracies should employ safeguards to prevent the misuse of information tactics. These include strict oversight, codes of conduct and authorisation.

Truthfulness: Above all, democracies should prioritise truthfulness in their information warfare tactics. They should avoid spreading false or misleading information and instead seek to provide accurate and reliable information to the public.

Key takeaways

– Read and understand the principles set out in the Civil Service Code and the GCS propriety guidance, and apply them to your communication strategy.

– Ethical conduct is a powerful weapon to build trust and must be adhered to. Trust is easily lost if it is seen to be compromised.

– Where activity is not stated, this must be a conscious decision based on operational security or because of the benefit it would give to our adversaries.

Final thoughts: The emerging challenge and solutions

The thinking and practice on information statecraft continues to develop. Recent publications have highlighted the contrasting approaches taken by different states.

In their seminal work ‘Beijing’s global megaphone on Chinese media operations’, Freedom House Group wrote of China’s “dramatic expansion in efforts to shape media content and narratives around the world”. They claimed that the government had created a “multifaceted adaptive and complex set of tactics that are used across varied environments. They combine widely accepted forms of public diplomacy with more covert, corrupt and coercive activities that undermine democratic norms, reduce national sovereignty, weaken the financial sustainability of independent media and violate the laws of some countries”.

In their view, the Chinese state has taken a conscious decision to expand state media, cultivate foreign media, deliver free content into the media outlets of global middle ground powers, purchase media organisations where they were able to and launch disinformation campaigns, and suppress media outlets that criticise the Chinese state.

A contrasting approach to this is set out by the Rand Corporation in their research report, ‘The role of information in U.S. concepts for strategic competition’. They outline a strategy for using information in an era of nation state competition. They argue that this requires a “whole-of-government response” and “a campaigning mindset”, strong international partnerships, a transparent approach, a plan that embraces creativity, placing resources in the right areas, and an “increased risk tolerance”. The paper also argues that empowering civil society is a critical tool, “bolstering civil society in terms of social cohesion, effective law enforcement, and independent and responsible media and legitimate transparent and effective governance”.

Many of these points are picked up in this information statecraft toolkit. However, as the thinking and practice of information statecraft develops, it remains important to continuously review and engage with the emerging material to refine our doctrine and approach.

Conclusion: Making our case – influence for good

This toolkit brings together the work of many government communicators. It builds on our history as a profession that has served through war and peace and particularly focuses on the lessons we have learned in the modern digital information age. It is designed to give you the tools to deliver proactive and credible communication to support the UK’s international objectives and help our allies to deliver a world where trade flows, people choose their governments and the international laws and the rights of Nations states are observed and protected. It requires brave, bold and confident communication using ministers but also ambassadors and other spokespeople, including credible third parties who can help us make our case. It requires the use of images and visual communication more generally alongside the traditional scripts and narratives.

Our allies are always impressed by the ability of the UK GCS to act in a way that is united, capable and campaigning. They respect our ability to cooperate across departments and agencies, and they admire our high levels of capability and professionalism. They adopt our campaigning model because they can see it is a way to bring coherence to communication in a crowded information environment. We should continually work to earn this respect and demonstrate our impact. UK Government communication is itself an element of soft power and an area we have comparative advantage in, which supports our allies and builds respect for our national reputation. That is why this toolkit is designed to bring together our best practice and spread that across our systems.

And it is also true that our adversaries prefer to live and act in the dark; to disassemble, to frighten and to divide. They do not want us to communicate because they know we are highly capable and that our stories, content and events inspire people in a way that buttresses the values we hold and gives hope to people around the world that democracy under law and legal rights will prevail. It should also serve a purpose to illustrate that communication is more science than art. There is a right way to communicate. It is a modern profession and there is both doctrine and evidence about what works and what does not work. This is the theory behind PITCH – that uniting partners, using insight, gathering trusted voices, delivering compelling content and doing that ethically will achieve our goals through the enabling power of information.

I’m very grateful to GCS colleagues, particularly Alice Preedy and Leonie Blakeway, who have worked hard in the production of this document. It has also been a truly collaborative cross-government effort with significant assistance from teams in the Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Defence and the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office.

Alex Aiken, Executive Director, Government Communication Service, December 2023

Annex A: PITCH checklist

Partners and allies

- Be clear about shared policy and operational goals which communications can inform, shape and help execute.

- Integrate your communications delivery with policy, diplomatic activity and operational activity, ensuring message discipline and consistency.

- Continuously monitor and reflect on the learnings and impact of your communications. Respond rapidly to any changes in the operational environment.

- Build networks of contacts in partner governments, sharing best practice and exploring how to co-deliver messages.

Insight

- Gather insight to build a rounded and clearly defined picture of your target audience and the local context.

- Use this insight to inform your campaign’s approach, including the channel strategy, messaging, timing and resourcing.

- Understand your audience’s vulnerability to misinformation and disinformation using the information vulnerability mapping approach.

- Use RESIST 2 to monitor, identify and respond to misinformation and disinformation appropriately, as part of your wider proactive communication strategy.

Trusted voices

- Identify groups or individuals that could help you to (more) effectively land your key messages. Consider the goals, subject matter and target audience of the campaign in order to select the most appropriate, relevant and credible third parties.

Compelling content

- Use striking visuals, especially in video form where possible.

- Consider the full range of channels available to deliver your messaging – from traditional diplomatic means and media relations, to new digital platforms.

- Ensure your communications are based on strong proof points, anchoring in local programmes/development where possible.

Honesty & integrity

- Read and understand the principles set out in the Civil Service Code and the GCS propriety guidance, and apply them to your communication strategy.

- Where activity is not stated, this must be a conscious decision based on operational security or because of the benefit it would give to our adversaries.

Annex B: Core communications tools

This guide should be used in conjunction with the following core tools created by the UK Government for communications best practice.

OASIS framework

All government communicators use ‘OASIS’ as a framework for planning communication activities and campaigns. PITCH should be leveraged as a supplementary model for developing an international communications strategy. It is best used at the ‘Strategy’ and ‘Implementation’ stages of OASIS to explore and inspire communication tactics, but aligns to each of the five stages, as outlined below.

- Objectives – setting objectives means understanding and quantifying the changes in public behaviour and/or building understanding of a policy goal or simply increasing awareness of an institution or policy. This stage of OASIS relates directly to the ‘Partners and allies’ element of PITCH, which focuses on understanding the policy goal and which partners within the organisation need to be part of the team to deliver the campaign.

- Audience – PITCH’s focus on insight relates directly to the ‘Audience’ stage of OASIS campaign planning. In both doctrines, there is an absolute requirement to understand the needs of the audience.

- Strategy – the GCS defines strategic communication as “influencing audiences for public good by marshalling the necessary resources to achieve agreed goals. This is achieved through organisational unity: the co-ordinated use of all the communication tools available, underpinned by research and given coherence in a story and communication products. This is set out in a single plan, working to milestones and properly evaluated.” Many communication plans fail because they do not co-ordinate or have coherence and lack organisational unity. The strategy underlying PITCH is to develop a unified approach with partners, deliberately focus on using trusted voices and stick to a truthful approach, which together provide a coherent impact.

- Implementation – the ‘Compelling content’ element of PITCH directly aligns with the implementation stage of the OASIS campaign doctrine.

- Scoring – traditionally, campaign evaluation has been conducted at the end of a campaign. This is why it is the fifth element of the OASIS doctrine. We have deliberately placed the continuous evaluation element of PITCH in the first phase, that of partnerships, in order to emphasise the link to objectives and the importance of working with internal partners to track and adjust the campaign as it is delivered.

RESIST 2 Counter Disinformation Toolkit

The RESIST 2 toolkit enables communicators to develop a response that can be used when dealing with all types of manipulated, false and misleading information. Its aim is to reduce the impact of false, misleading, and manipulated information on UK society and our national interests, in line with democratic values.

- Recognise: understand and spot false and misleading information

- Early warning: learn how to monitor the information environment

- Situational insight: transform monitoring data into action

- Impact analysis: assess the impact and threat of false and misleading information

- Strategic communications: discover how to implement communication strategies

- Tracking effectiveness: evaluate the impact of strategic communications

PITCH builds on the ‘Strategic communications’ element of the RESIST framework.

Evaluation Framework 2.0

Building on the principles for evaluation set out as part of the OASIS model, the Evaluation Framework 2.0 provides guidance on how we can measure the success of our communications work and appraise our activities, including by:

- setting baselines and measurable criteria to demonstrate change

- defining outtakes and outcomes

- factoring in causal links.

COM-B model for behaviour change

The COM-B model explains what conditions are required for behaviour change to occur, and provides a framework for understanding and exploring the barriers to behaviour change that audiences might face. According to the COM-B model, in order to do a behaviour an individual must have the capability to do it, the motivation to do it, and external factors must provide the individual with an opportunity to do it. This model helps to define the role for communications in achieving the desired behavioural outcome.

Modern Communications Operating Model (MCOM) 3.0

The MCOM 3.0 outlines the principles needed to set up, manage and develop a high-performing communication team. At its heart is a multi-disciplinary approach. Every communication team should have the core seven MCOM disciplines represented to differing degrees depending on organisational need, size and focus:

- External affairs

- Marketing

- Internal communication

- Media

- Strategic communication

- Data and insight

- Digital communication

This does not mean needing seven separate siloed teams. Instead, it means having those skills somewhere in the team and available to others.

GCS Horizon Review 2023

The GCS Horizon Review into responsible innovation is available for GCS members. It looks at emerging technologies and applications of data within marketing and communications.

Annex C: Further reading

Listed below are further external resources which you may find helpful on the subjects of information statecraft and strategic communications. You do not have to use the external resources we link to and this is not an exhaustive list.

The inclusion of a publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Government Communication Service or any other government department or agency.

- ‘The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict’, Mark Leonard

- OECD report on public communication: The Global Context and the Way Forward

- ‘Twenty-first-century diplomacy: Strengthening US diplomacy for the challenges of today and tomorrow’, Jeffrey Cimmino and Amanda J. Rothschild, Atlantic Council

- ‘Discursive statecraft: China’s information operations’, Hannah Bailey, Council on Geostrategy

- ‘The Geopolitics of information’, Eric Rosenbach and Katherine Mansted, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

- ‘How Ukraine used Russia’s digital playbook against the Kremlin’, Mark Scott, POLITICO

- ‘The power of information to build resilience in a volatile world’, Alex Aiken, NATO Review

- Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2023

- ‘The role of information in U.S. concepts for strategic competition’, Rand Corporation, research report 2022

- ‘Beijing’s global megaphone: The expansion of Chinese Communist Party media influence since 2017’, Freedom House