Strategic Communication: MCOM Function Guide

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points: 2

This guide developed by the GCS Heads of Strategic Communication network identifies the core functions of a strategic communication team, key principles of structure and practice.

We updated the guide in April 2021.

Details

Contents:

- Definitions

- Introduction

- Strategic communication: core functions

- Building capability: guidance, tools and resources

- The core functions in action: case studies and article

Definitions

The role of strategic communicators

“Strategic communicators provide the campaign plan to successfully communicate a public policy or service. They shape the policy, generate ideas, commission research to gain insight, identify realistic goals and bring together the means necessary to implement the goals of the plan. They agree on the ways of delivery that will work and guide the implementation and assess impact to see whether the objectives or ends have been achieved.”

Strategy

A definition of strategy from the Royal College of Defence Studies:

“A course of action that integrates ends, ways and means to meet policy objectives.”

Strategic communication

The Government Communication Service (GCS) definition:

“Influencing audiences for public good by marshalling the necessary resources to achieve agreed goals. This is achieved through organisational unity; the co-ordinated use of all the communication tools available, underpinned by research and given coherence in a story and communication products. This is set out in a single plan, working to milestones and properly evaluated.”

Introduction

Government communicators help the public understand the government’s vision and priorities. They inform people about public services, explain policies, encourage people to lead safe and healthy lives, counter misinformation and disinformation, and promote UK interests internationally.

At the heart of this work is strategic communication. Without it, activity becomes tactical, delivers short-term outputs and leads to duplication. Communicating strategically brings coherence. It looks beyond the day-today and seeks to influence target audiences to create long-term change.

Strategic communicators have a specific role in setting direction, guiding the implementation of activity (alongside other disciplines), ensuring measurable outcomes are achieved and telling the government’s long-term narrative.

Practitioners must do three things

First, understand audiences and their behaviours to effectively diagnose problems and advise on the most appropriate course of action. They must be close to the data and insight, understand the context that the GCS is operating in and spot long-term trends, risks and opportunities.

Second, when communication strategies are produced, practitioners will consider the range of interventions and communication levers at their disposal, ensuring the most effective combinations are chosen. They must make deliberate choices about how to focus efforts to achieve outcomes.

Third, they must understand complex government policies and be able to define the role of audience communication in delivering them. They will evaluate activity to demonstrate impact and adopt a test and learn approach so that government communication continuously improves.

Strategic communication is a valuable tool that supports the government in communicating the complexities, uncertainties and challenges of the modern world. It brings coherence to communication activity, sets direction, puts audience understanding at the heart of policy and service design and ensures the most appropriate combination of government levers are brought to bear on an issue.

Strategic communication: core functions

Strategic communication teams provide leadership to colleagues by setting direction and making key decisions about what, when and how to communicate. Their value and skill lie in understanding complex data, devising strategies and evaluating outcomes.

Listed below are the core functions that strategic communication teams and practitioners must be able to undertake with confidence and appropriate expertise. They are structured around the four stages of the strategic communication planning process – insight, ideas, implementation and impact.

Effective strategic communication must bring together ends (goals), ways (tactics) and means (resources) to achieve measurable changes in behaviour or perception.

Strategic communication teams should have the requisite capability in these areas to deliver effective day-to-day operations. They should also enable appropriate professional development to optimise team capability.

Insight – develop a deep understanding of audiences, channels and context

Understand the evidence base and context

Practitioners will develop a deep understanding of audiences through a wide range of sources including user research, stakeholder intelligence, social listening and behavioural science. They will interrogate big data and navigate an increasingly fragmented media landscape. They will use this knowledge, along with a rich understanding of the operating context, to develop strategies, inform communication objectives, craft messages and evaluate outcomes.

This involves:

- understanding audience segments – their attitudes and beliefs, awareness and knowledge, motivations and barriers to behaviour change, and their media consumption

- understanding the principles of behaviour change and the COM-B framework

- keeping abreast of new media developments and trends

- understanding the operating context – political, economic, sociological, technological, legal and environmental

- analysing developments, insights, stakeholder feedback and commentary from the external environment to understand perceptions of the government and its policies

- regularly bringing together existing quantitative and qualitative research to inform communication plans

- sharing learning from previous communication activity and applying industry best practice to shape future activity

Undertake short, medium and long-term planning

Practitioners will undertake strategic planning to inform decisions about what is communicated and when. They will mitigate risks and act upon opportunities to maximise impact and ensure communication is effectively executed.

This involves:

- owning and maintaining a list of communication activity and announcements in the short, medium and long-term

- sharing intelligence with other communication teams to align and alter plans so that government communication is effectively joined up

- working with policy and operations colleagues to anticipate what messaging audiences will need in the short, medium and long-term

- identifying and acting upon emerging threats and opportunities

- managing risks, issues and dependencies

- effectively triaging incoming requests for communication support on new or emerging priorities

Ideas – develop strategy and provide strategic advice

Develop communication strategies

Practitioners will develop insight-based, audience-focused strategies to set direction. These will be co-designed with colleagues from other communication disciplines, policy and operations (as appropriate). These strategies could be an annual communication plan, setting out the key programmes of work for the year ahead, or plans for major campaigns and projects.

Developing and drafting a strategy involves the following steps:

- agreeing the strategic priorities with senior leaders and translating them into communication objectives and success measures

- conducting audience segmentation using insight and data

- assessing strategic choices/tradeoffs, drawing on theory of change and principles of behaviour change

- demonstrating the synergy between communication and other interventions

- aligning the strategy with UK government priorities and wider government communication initiatives

- crafting tailored messaging for target audiences, identifying powerful proof points and opportunities to tell the government’s story in an engaging way

- identifying and allocating budget for activities and managing budgetary approvals

- agreeing the roles and responsibilities of each communication discipline to successfully deliver the strategy

- gaining sign-off and promoting the strategy to ministers, senior officials and colleagues

Provide strategic communication advice to policy and operations colleagues

Practitioners will work with policy and operations colleagues to jointly diagnose issues at the very start of policy development and service design (see the Engagement Framework). This might be during business planning to create an annual communication plan or for a specific project or issue that emerges during the year. When communication, policy and operations colleagues work together it leads to improved problem solving, ensuring the most appropriate combination of government levers are selected.

This involves:

- using insight and evidence to act as the voice of the audience during policy development and service design

- advising policy and operations colleagues on the role communication can play in developing and implementing the policy or service

- taking a united course of action and devising strategic communication objectives and evaluation metrics that contribute towards joint goals

- knowing when to bring in other specialists such as digital experts, user researchers, behavioural scientists, commercial colleagues as well as drawing on specialist knowledge from across GCS

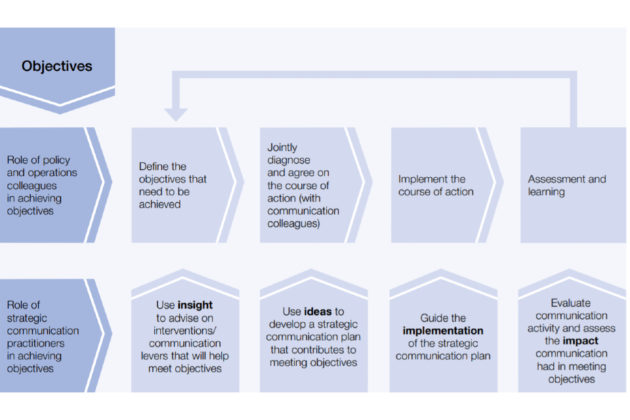

The Engagement Framework

Click on the image for a larger format.

The Engagement Framework (above) outlines how policy, operations and strategic communication colleagues should work together, from the very start of policy development and service design, right through to implementation and evaluation.

Implementation – steer the delivery of strategies and plans

Guide the implementation of communication strategies and plans

Practitioners will lead their colleagues by steering the implementation of communication activity and monitoring progress.

This involves:

- providing strategic oversight to guide the delivery of strategies and plans

- regularly reviewing progress (monthly and quarterly), adopting a test and learn approach and offering interventions if progress is not being made

- co-ordinating big set pieces, such as major announcements, that require delivery from all communication disciplines

- motivating every government communicator to understand and use the government’s overarching narrative to help tell the long-term story

Impact – evaluate activity and ensure demonstrable outcomes

Measure and evaluate communication outcomes

Practitioners will ensure there is an appropriate and robust approach to evaluating strategies and plans. They will measure what matters to assess the effectiveness of communication activity in the short, medium and long-term.

This involves:

- monitoring communication activities throughout the implementation phase by collecting, analysing and evaluating output and outcome measures

- aligning communication and policy evaluation (where appropriate) to identify the contribution communication has made to the overall mix of interventions

- circulating evaluation highlight reports to senior officials and ministers

- sharing lessons learnt to inform and improve future communication plans

Building capability: guidance, tools and resources

Building capability

Strategic communication practitioners must be able to:

- develop SMART communication objectives

- understand the principles and application of behavioural theory

- carry out basic desk research and analysis using a range of insight tools and resources

- develop and deliver OASIS plans and apply GCS insight and evaluation frameworks

- have personal impact and leadership skills to persuade and influence

To develop and strengthen strategic communication capability, practitioners can draw on the following guidance, tools and resources:

GCS guidance, tools and resources

The GCS Academy is an online resource listing training opportunities, events and resources by communication discipline.

The GCS Professional Competency Framework is designed for all professional communicators in government up to, and including, Grade 6. The framework helps practitioners broaden their range of skills under the four competency headings: insight, ideas, implementation and impact.

The OASIS Campaign Guide is for all government communicators, regardless of discipline or organisation. It helps plan communication and structure thinking to ensure activity is effective, efficient and evaluated.

The principles of behaviour change communications sets out how government communicators can use a behavioural approach to design and implement effective campaigns.

The GCS Evaluation Framework standardises the measures that should be adopted to evaluate each type of communication activity. The use of consistent data and reporting means that government communicators can draw more meaningful conclusions about their work. It also assists with benchmarking and target setting.

GCS professional development

The GCS Career Framework provides guidance on how to develop your career within the GCS.

Courses and events available to government communicators are listed on the GCS website.

These include:

- Introduction to Strategic Communication

- Using Behavioural Science to Communicate Strategically

- Advanced Strategic Communication

The core functions in action: case studies and article

The following case studies and article illustrate how practitioners apply the four core functions (insight, ideas, implementation and impact). They provide a useful resource for strategic communication teams across GCS and for all public service communication professionals.

Case Study 1 – Keeping citizens safe during the COVID-19 pandemic

Challenge

COVID-19 remains the biggest peacetime crisis the British people have faced in living memory. To effectively mitigate the spread of the virus, citizens in the UK needed to adopt new behaviours.

To drive this behaviour change, the government’s National Resilience Hub was formed in March 2020. It developed an integrated cross-government communication campaign to deliver this change. Ultimately protecting the public from illness, infection and death, while safeguarding livelihoods.

Approach

To generate the right behaviour change and set the strategic direction, the hub’s strategic communication team developed a framework to meet the following objectives:

- explain the government’s COVID-19 strategy, both nationally and locally, in order to build confidence and trust

- build understanding of and compliance with the behaviours every individual needs to take to contain the spread of the virus

- reassure the public of the government’s action through clear messaging delivered via trusted voices

SALT Framework

The overall approach was to simplify, amplify, localise and target (SALT Framework) all messaging. We needed to engage all members of society, particularly those who are harder to reach, with vital public health messages and bring clarity to a complex communication picture. SALT was developed utilising the expertise of researchers, behavioural scientists, marketing experts and other communication functions.

- Simplify – overall compliance was highest when rules were simple, tangible and easy to follow: Hands, Face, Space.

- Amplify – messages were amplified across channels by identifying and activating trusted voices and influencers. This included direct partnerships with over 300 press publications. We also worked with in-house media, PR and advertising agencies, utilising their expertise to ensure we could maximise amplification of messaging across the nation.

- Local – locally led, trusted voices have a far better chance of reaching and speaking to people directly. We worked with the communication teams of 343 local authorities on a daily basis, as well as the devolved administrations, to upskill their communication teams. We supported them to develop their own local and regional campaigns that championed local voices.

- Target – communication must not treat the general public as a homogeneous group. We conducted research to understand each area of society through daily focus groups and localised feedback. We used this knowledge to adapt and tailor all communication accordingly, particularly to engage the harder to reach and those that had been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Our multichannel communication strategy had a particular focus on targeted community engagement, addressing language, cultural, and accessibility barriers.

Impact

Our COVID-19 campaign reached 95% of adults, the NHS COVID-19 app has been downloaded more than 21 million times, and seven in eight people are aware of vital preventative behaviours of Hands, Face, Space.

Our communication has generated significant changes to behaviour among the general public, reducing the spread of COVID-19 and ultimately saving lives.

Case Study 2 – Preparing citizens and businesses for the Brexit Transition Period

Challenge

Brexit Transition Period changes were set to impact up to 16 million people and 5.9 million businesses. Our audiences were disengaged and overwhelmed by COVID-19 and we needed to prepare them for the changes ahead.

To do this we:

- developed audience-first communication plans to support citizens and businesses in preparing for the changes

- developed and embedded a consistent narrative for the Brexit Transition Period

- supported the government’s goal of minimising disruption (in Northern Ireland, this meant proactively managing issues that could lead to a worsening of relations)

The result was the government’s public information campaign, ‘Check, Change, Go’.

Approach

We worked with policy colleagues to identify 120 actions that audiences may need to take to prepare for the changes. These were prioritised – using insight – by population size, impact of inaction (e.g. direct impact to the audience or to the economy) and ability for paid marketing to make an impact.

We broke the mould of government communication to meet the challenge by:

- bringing 15 government departments together to run activity under one government campaign brand

- forming a central campaign team to deliver paid media support and co-ordinate activity such as PR and partnerships, amplifying department-led communication, and delivery of content via third parties

- creating OASIS plans for five target audience groups: citizens, businesses, borders (hauliers and traders), organisations funded by the EU, and Northern Ireland (citizens and businesses); and segmenting further, for example, businesses into sectors to develop hyper-relevant messaging

- driving audiences to GOV.UK pages through a bespoke Brexit Transition Period Checker Tool, providing a personalised user experience and bespoke list of actions to take

- building a specific campaign arm for Northern Ireland, providing a mix of communication advice and delivery of bespoke paid marketing

Impact

The campaign generated 63 million visits to GOV.UK Brexit Transition Period content and more than five million uses of the dedicated Checker Tool. The government’s reasonable worst-case scenario was avoided, protecting £250 million of cross channel trade per day, and compliance with the new rules was much higher than expected.

We also established a new way of delivering cross-government campaigns in Northern Ireland. This resulted in a more joined-up and bespoke approach to a politically sensitive, yet highly engaged, part of the UK.

The challenges of creating a strategy

“Can we just tweet something?”

By Lucy Denton, Head of Communication at the Office of the Public Guardian.

Communication can be an undervalued profession. Don’t believe me? Talk to any communication practitioner who has been asked to “just tweet something”.

With so many people blogging and tweeting from personal accounts, it is easy to think that delivering communication is a piece of cake. On top of that, our work is often seen as a series of individual outputs – posters, events, blog posts, press releases etc. – and I am sure that is why the misunderstanding arises. The truth is that good strategic communication does not focus on the output. It has a plan and focuses on the outcome first.

The value of the strategy

Communication without a plan is just noise. For example, @KFC does not follow the Spice Girls and six guys called Herb just because it is funny! It is a simple strategic approach, perpetuated for decades, around their secret blend of 11 herbs and spices in the Colonel Sanders’ fried chicken recipe.

In government communication, we are unable to act on every request and need a way of managing and prioritising demands that come through. In this case, a communication strategy is our greatest ally.

With clear aims and objectives, we can show our return on investment, not simply to ministers and senior officials but also to our colleagues across the organisation.

The strategy for a strategy

Strategies do not have to be complicated. Focussing on outcomes is key. It means taking the time to stop and ask why we are doing something and why we want to put out specific messages.

Here are three tips you can use to make this process simple:

- Never talk assets: your colleague comes into the meeting, sits down and says, “I want a video”. This is not a good start. As soon as people start to talk tactics or design assets, I step back and explain that we need to talk about the big picture first.

- Focus on the goal: the most important thing for me when developing a communication strategy is knowing what needs to be achieved and what good looks like. You may not realise it, but as you start to form your communication objectives, you will also be developing the ways to measure the success of the strategy.

- Remember the value communication brings as a lever of government, it can:

- influence attitudes and behaviours

- support government services

- inform, support and reassure during times of crisis

- enhance the government’s reputation at home and abroad

- help meet statutory or legal requirements

Think about these tips when considering your options and the combination of levers you use to shape your strategy. There is value in taking a step back and reflecting on the approach before rushing into implementation.

Plan the delivery

When you have done the thinking, established objectives and used insight to target audiences effectively, you can bring your strategy into play. What activity will you do in the first week or month or year? What are the milestones you can use as anchors? You can be flexible within your timescales but it is good to have an idea about how the campaign should look and start bringing all the different elements together.

The pitch

I like to think communication teams work best when they operate as an in-house agency. By using an agency-style approach, we give ourselves more credibility. We get held to account on our deliverables and we are seen as experts and specialists.

The more we get out and show the value that audience-led, outcomes-driven communication can deliver, the more we promote the value of government communication.

And in time who knows?! People might stop saying, “just tweet something” and ask us what approach we recommend as communication professionals