Crisis communication: A behavioural approach

This guide explores how to anticipate public behaviour in a crisis. The approach it sets out is relevant and applicable to all communicators working in a fast-paced environment.

This guide is for anybody who works in communications:

- for those who are new to crisis communications work, the guide aims to be accessible as an introduction

- for those who are more experienced, this guide introduces new techniques and insights that will build on existing expertise

The guide was developed with local and national government communicators in mind; however, the approaches it sets out will still be applicable to communicators in other sectors that need to communicate with audiences in fast-moving situations.

On this page:

- Foreword

- About this guide

- Introduction

- What will people do in a crisis?

- How can communications encourage the right behaviours in a crisis?

- How can communications discourage harmful behaviour in a crisis?

- Case study: COVID-19 pandemic

- References

- Acknowledgements

Foreword

In the last few years, the world has faced several major crisis events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and resulting global supply chain challenges. Crises pose many challenges for communicators – events can evolve rapidly, information and evidence are often in short supply, and people may respond in ways that can seem unpredictable.

By necessity, then, crisis communication has historically been informed by common assumptions about public behaviour – that people are prone to panic, that the public pose a danger to themselves and others, and that the role of authorities is to calm, control, and reassure. These assumptions might seem intuitive – but do they stand up to scrutiny?

Recent events have put the spotlight on existing and emerging behavioural science research about crisis responses, challenging many of these deeply-held assumptions, and giving us a more realistic and nuanced view of how people respond to crisis situations. I am pleased to introduce this new guide, which sets out this evidence, and explains how communicators can apply it to develop powerful and effective crisis communications plans.

I hope that this guide will bring these exciting insights and techniques to a wider audience, helping government communicators across the UK (and beyond) design communications that are based on the best available evidence about how people really behave when faced with a crisis.

Simon Baugh, Chief Executive of Government Communication Service

About this guide

The guide opens with a summary of key points, followed by an introduction and definition of terms.

The main guide is divided into three sections:

- firstly, it explores how to anticipate public behaviour in a crisis, challenging some common assumptions and introducing new evidence (what will people do in a crisis?)

- secondly, it sets out approaches to encouraging people to adopt appropriate protective behaviours (how can communications encourage the right behaviours in a crisis?)

- thirdly, it discusses how to mitigate harmful or dangerous behaviours (how can communications discourage harmful behaviour in a crisis?)

Finally, the guide concludes with a case study of the COVID-19 pandemic, to demonstrate how the concepts and behaviours discussed in the guide played out in a real-world crisis situation.

Introduction

During a crisis or emergency, communication is one of the most important levers that the Government can use to achieve its objectives and support the people of the UK. Public bodies must be the trusted source of accurate, relevant, and timely information during these situations, to coordinate response activities, maintain security, and direct people to help and support (Reference 10).

Poor or absent crisis communication can seriously hinder the response effort, and the growing threat of disinformation from hostile actors has further complicated the challenge.

By their nature, crisis and emergency situations are unstable and unpredictable, making it difficult to plan ahead and anticipate public behaviours. This is why crisis communication approaches are typically informed by several key assumptions about how the public will respond and the behaviours they will engage in.

However, there is a large, and growing, body of behavioural science literature about crisis communications (partly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic) that challenges common assumptions about public behaviour, and explores why some communications strategies backfire or have unintended consequences.

This guide aims to draw on this evidence to set out a behavioural science-informed approach to crisis communications. The guide will contain some theoretical background on key behavioural science principles of crisis communication, but will focus on actionable advice for communications professionals operating in a crisis context.

Definitions

- Crisis: an inherently abnormal, unstable and complex situation that represents a threat to the strategic objectives, reputation or existence of an organisation (Reference 8)

- Emergency: an event or situation which threatens serious damage to human welfare, the environment, or the security of the UK. Additionally, to constitute an emergency, an incident or situation must also pose a considerable test for an organisation‘s ability to perform its functions (Reference 8).

Throughout this guide, the term “crisis communications” will be used to refer to Government communications during a crisis or emergency.

What is behaviour, and why does it matter in a crisis?

Behaviour change is an essential outcome of crisis communications. Behaviours are observable actions and are distinct from attitude changes, norms, knowledge, desires, and beliefs. It is vital to focus on behaviours as, in a crisis situation, it is primarily behaviour that will determine outcomes. In other words, it is what people actually do that matters for their survival.

Beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and norms can all be significant influences on behaviour, but they are not behaviours themselves. Being aware of flood risk might make you more able to engage in protective behaviours, but awareness alone is not sufficient, and should not be the ultimate goal or outcome of crisis communications.

Crisis communications may also aim to stop people from engaging in harmful behaviours. The following sections will detail how communications can effectively enable effective protective behaviours, and discourage harmful ones.

What will people do in a crisis?

What common assumptions are made about crisis behaviour?

In a crisis or emergency, policymakers and communicators need to make some assumptions about how people will behave, to inform emergency management practices and the crisis response (Reference 6).

When it comes to assumptions, disaster films have a lot to answer for! Common scenes depict members of the public fleeing and screaming in apparent blind panic, harming themselves and others in the process, or inversely, staying put and ensuring their destruction through stubbornness or ignorance (Reference 19).

Depictions of a public who fail to pay attention to advice and reliably over- or under-react to danger have influenced media accounts of disasters. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, people were described as “panic buying” toilet rolls and paracetamol, and governments around the world adopted strategies to avoid “mass panic”.

However, careful study of public behaviour across numerous crisis situations including the 7/7 bombings in London (Reference 3), Hurricane Katrina (Reference 26) and COVID-19, paints a very different picture of how people behave in reality.

True panic is rarely observed

“Panic” is technically defined as an “excessive feeling of alarm or fear… leading to extravagant or injudicious efforts to secure safety” in the Oxford English Dictionary, although it is frequently used more generally to refer to any feeling of fear or instance of uncoordinated behaviour (Reference 11). If we understand “panic” to specifically mean excessive fear leading to extreme overreaction and irrational behaviour, then evidence shows that panic in disasters is extremely rare (Reference 12). What may look at first glance like “panic” is often a logical response to a real perceived threat to meet a given need.

In research studies looking at more than 500 disaster and crisis events, the Disaster Research Centre at the University of Delaware found that panic “was of very little practical or operational importance”, as it was not found to be a significant influence on outcomes during such events (Reference 11). Studies find that responses that may appear like “mass panic” to an observer can later be understood as extremely reasonable reactions once details are known (Reference 5).

For example, running away is the recommended and sensible response to a potential firearms attack, but to an observer watching news footage of crowds pouring out of a train station, this behaviour may look like “mass panic” and appear highly chaotic. While these people may be experiencing intense fear, their actions (running away) are rational and in line with emergency advice. People may report observing or experiencing “panic” during a crisis situation, but what they are usually reporting are entirely reasonable feelings of fear. Even when people feel seriously afraid, this very rarely leads to chaotic and uncontrolled behaviour that puts others at risk (Reference 2). Rather, people tend to act to secure their safety and needs more generally.

In cases where public responses have unfortunately increased injuries or fatalities in the aftermath of an incident, this is often ultimately attributable to external factors, such as exits being locked or blocked and therefore is better understood as the outcome of design and organisational failures than of public panic (Reference 6).

Assuming that the public will panic and using this as the foundation of crisis planning can lead to flawed recommendations, and a misplaced focus on mitigating panic over more meaningful objectives (such as better organisational design during an emergency response).

People cooperate and support each other, even in a crisis

In contrast to the common perception of the public as prone to panic and self-interest, research shows that cooperation, altruism, and mutual support are defining features of public response to disasters. People go out of their way to help others rather than push them aside and flee, with normal manners for interpersonal conduct often being maintained even at critical moments (Reference 12). People tend to be organised in these efforts, frequently forming orderly queues, making plans, and distributing resources in a coordinated manner.

Communities typically “rise to the occasion” in crisis situations, often taking great efforts to support each other and provide assistance to the vulnerable, and authorities may be deluged with offers of assistance from volunteers, both trained experts and the general public (Reference 11).

“When the World Trade Center started to burn, the standards of civility that people carried around with them every day did not suddenly dissipate. The rules of behaviour in extreme situations are not much different from rules of ordinary life. People die the same way they live, with friends, loved ones and colleagues—in communities. When danger arises, the rule—as in normal situations—is for people to help those next to them before they help themselves.”

(Reference 2)

Stockpiling and excessive buying

Another common assumption in emergency situations, and one that is often propelled and exacerbated by the media, relates to excessive buying; often referred to as “panic buying” and “stockpiling”. Images of empty shelves and trolleys piled high with goods can be alarming, and can look from the outside like emotionally-charged and irrational behaviour. Often these images are also coupled with a narrative of ‘selfish’ individuals, fueling an (unhelpful) sense of ‘every person for themselves’ rather than fostering prosocial behaviours.

However, in most situations, excessive buying is not irrational or selfish at all and is driven by people responding to normal incentives. If an item is rumoured to be in short supply and is at risk of running out, then it is advantageous to buy extra. If shelves are frequently empty, people will have good reasons to go to the shop more often to secure supplies. If there are long queues to get fuel, then filling your tank and taking extra fuel home is a logical response to the situation.

For more information on reducing excessive buying, see the section ‘How can communications help maintain social order?‘.

How can we anticipate actual crisis behaviour?

If not panic, then what might we observe instead? Behavioural responses will vary depending on the specific type of crisis situation, but will normally be determined by a fundamental driver of behaviour – essential needs.

Regardless of the difficulty of the circumstances, the public will be highly motivated to meet their essential needs in a crisis. Since crises can sometimes inhibit authorities’ ability to respond immediately, individuals and local communities will typically need to take some actions for themselves to meet many (and in some cases perhaps all) of these needs.

By starting from these needs, and systematically thinking about how people will fulfil them and what obstacles they might face, it is possible to anticipate a range of likely public behaviours for any given crisis.

How to anticipate public behaviours in a crisis? A step-by-step approach:

1. Identify the public’s essential needs

Essential needs are relatively consistent across different situations. Essential needs that people will seek to meet during a crisis include, but are not limited to:

- Shelter: People need shelter to protect them from the elements.

- Security: People need to protect themselves and their possessions from harm.

- Hydration: People need a clean source of water.

- Food: People need access to edible food.

- Warmth: People will need to be able to stay warm to avoid health risks.

- Light: People need access to a light source once it is dark.

- Hygiene: People need to be able to wash themselves and dispose of waste.

- Health: People need to be able to access medical supplies and seek medical attention when needed.

- Safety from hazards: People need to be able to avoid hazards (for example, flood water).

- Information: People need to be able to access information, including information about the crisis and any instructions from authorities.

- Receiving assistance: People will need to be able to get help from others when needed, including the emergency services or neighbours.

- Money: People need access to their money to secure other essential needs.

- Contact: People need to be able to contact loved ones and authorities.

- Giving assistance: In many crisis circumstances, people display a strong desire to help others in perceived greater need.

- Entertainment: People need to keep themselves and children entertained to sustain morale and pass the time (particularly during protracted crises).

2. Identify the barriers to meeting those needs

The next step is to identify barriers to meeting those needs, and think about which barriers might be most likely in the given crisis situation. For example, in a pandemic situation, the public may not face significant barriers to obtaining water, while a flood poses more barriers to this need if water supplies are affected. The COM-B model (Reference 14) may help communicators identify different types of barriers.

3. Identify the behaviours the public might engage in to meet those needs

The third step is to identify the likely behaviours that the public will engage in to meet those needs, considering the barriers you identified. Behaviours may be similar to those observed in previous crisis situations, or unique to the current situation in hand. You can consider how people might try to overcome these barriers in a crisis situation, which may include behaviours that are normally considered unsafe or illegal.

For example, if water supplies are cut off in a flood situation, people might try to leave their homes to obtain water, potentially putting themselves at risk.

At this stage, you should have a clear understanding of the range of possible public behaviours in response to a given crisis.

4. Identify potential consequences of these behaviours, and plan how to mitigate negative consequences

The fourth step is to identify potential consequences of these need-seeking behaviours, particularly high-risk consequences (for example, if people may put themselves in danger or unwittingly expose others to harm).

You can identify what actions could be taken by the government, either in advance or during a crisis to mitigate the negative consequences and facilitate any positive ones.

Positive consequences may arise from the fact that, as noted above, many people will also want to help others they perceive as being in greater need than them.

Helping others may be considered an essential need in its own right, as a key way that people cope with a sense of fear or helplessness in a crisis situation.

Once this analysis has been completed for each need, you will be left with a detailed understanding of how the public may respond to the crisis. This can be used for crisis management and communications planning either during or in anticipation of a given crisis.

Example: An essential-needs-based analysis

The following table provides an example behavioural analysis of one need (food) in a specific crisis scenario (a national power outage).

| Actions to meet the need | Barriers to taking action | Resulting behaviours and consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Consume food supplies at home | * Consume food supplies at home * Perishable food is out of date * No electricity/gas to cook food * No refrigeration * Short supplies of non-perishable items | * Consume expired food; become unwell * Consume incorrectly-stored food; become unwell * Consume non-perishable items (if available); remain healthy |

| Purchase food from shops | * Cannot access shops safely * Electronic payment systems not functioning * Shops not fully stocked due to outage | * Abstain from food; become weak and unwell * Buy large volumes of non-perishable food from shops that are open * Leave home to obtain food from neighbours |

The table lists 2 examples of actions the public may take to meet the essential need of food: consume food supplies at home and purchase food from shops. It also lists the barriers to taking each action, and the behaviours and consequences that may arise as a result of taking those actions.

How does trust in government, or lack of it, influence crisis behaviour?

Trust in government and authorities has a significant impact on whether individuals will listen to government communications and follow advice. Where trust is low, people may not engage with government messages and may seek alternative sources of information, reducing the effectiveness of communication.

The determinants of trustworthiness have been widely explored, and researchers have determined that there are three core factors that influence how trustworthy governments (or other organisations) are perceived to be (Reference 13):

- competence: whether a government delivers results and follows through on its commitments.

- integrity: whether a government acts with integrity, tells the truth and acts consistently with its values and promises.

- benevolence: whether a government is concerned for the wellbeing of its citizens and aims to improve their conditions.

During a time of crisis, there is likely to be significant public uncertainty about what to do. As discussed previously, panic is an unlikely response – instead, most members of the public will be looking for clear and timely advice from an authority to help them decide what action to take.

If people do not trust governments to tell the truth and act in the best interest of the public, then they will be less likely to perceive government information about risks as credible. They might also lack confidence in government advice about protective behaviours. This might reduce audience willingness to act and respond appropriately in crises.

Also, if government information is not trusted, unwelcome messengers may fill the gap left behind. People will continue to look for direction and information and so alternative sources of advice may take precedence, reducing government ability to keep the public informed about risks and advise on protective behaviours. Disinformation flourishes in these circumstances.

How can communications encourage the right behaviours in a crisis?

Desired behaviours in a crisis situation will depend entirely on the nature of the crisis. They can range from the preventative (like keeping a supply of tinned food) to the reactive (like evacuating a disaster zone).

Some crisis behaviours will be brand new to people when they suddenly become necessary (like running from danger), while other behaviours might be more familiar (like washing hands).

As discussed in the introduction, it is important for communicators to focus on behaviour change as the primary objective in a crisis, rather than on attitudes and beliefs. While attitudes and beliefs can influence behaviours they are not sufficiently protective unless they translate into behaviour change.

For example, communications may set out to increase concern about flood risk in a particular region, reasoning that being concerned about flood risk might lead people to prepare emergency packs. While this may be true for some, there are likely other influences on whether a person prepares an emergency pack or not, and successfully increasing “concern” as the key metric does not guarantee the desired behaviour change.

How should we communicate in a crisis?

An effective approach to crisis communication (Reference 25) derives from the expertise of John Krebs, former chair of the Food Standards Agency with ample experience in crisis management. This framework provides a useful basis for crisis communication, setting out how and what the government should communicate to the public to reassure, inform, and promote desired behaviours.

How can we use the Krebs method to communicate in a crisis?

- How to communicate

- Communicate consistently and frequently

- Use trusted sources and messengers

- Set expectations that information may change quickly as more is known

- What to communicate

- Tell the public what is known.

- Tell the public what is not known, emphasising the uncertainty.

- Tell the public what actions the government is taking, and why (this may include actions to mitigate the crisis, and actions to reduce uncertainty).

- Tell the public what they should do, and why.

- Tell the public when to expect more information.

Example: Enhancing crisis communications through use of the Krebs method

A message about flooding without the Krebs method:

“There is currently serious flooding in the region, and we know that some households are without power. We don’t yet know the cause of the issue and can’t answer questions about how long power is likely to be out, so please wait for further information.”

A message about flooding that applies the Krebs method:

“There is currently serious flooding in the region, and we know that at least 1000 households do not currently have access to power. We don’t yet know when power will be returned, but it is expected to be more than 24 hours from now, and possibly up to 5 days.

Authorities are in the area now, working with energy companies to identify the issue and implement a plan to get the power back on as soon as possible. Until then, please stay indoors and do not attempt to cross flood water. Call the phone number below if you need urgent help.

This information will be updated at 8 PM as we find out more about the damage caused.”

How should we communicate about threats and risks?

In many crisis situations, communicators will need to explain to the public that they are facing a serious threat or risk. Messaging that seeks to shock people into action out of fear can fail to spur behaviour change and may cause other negative consequences. Messages about threats and risks must therefore be carefully designed to encourage audiences to act, rather than alarming or alienating them.

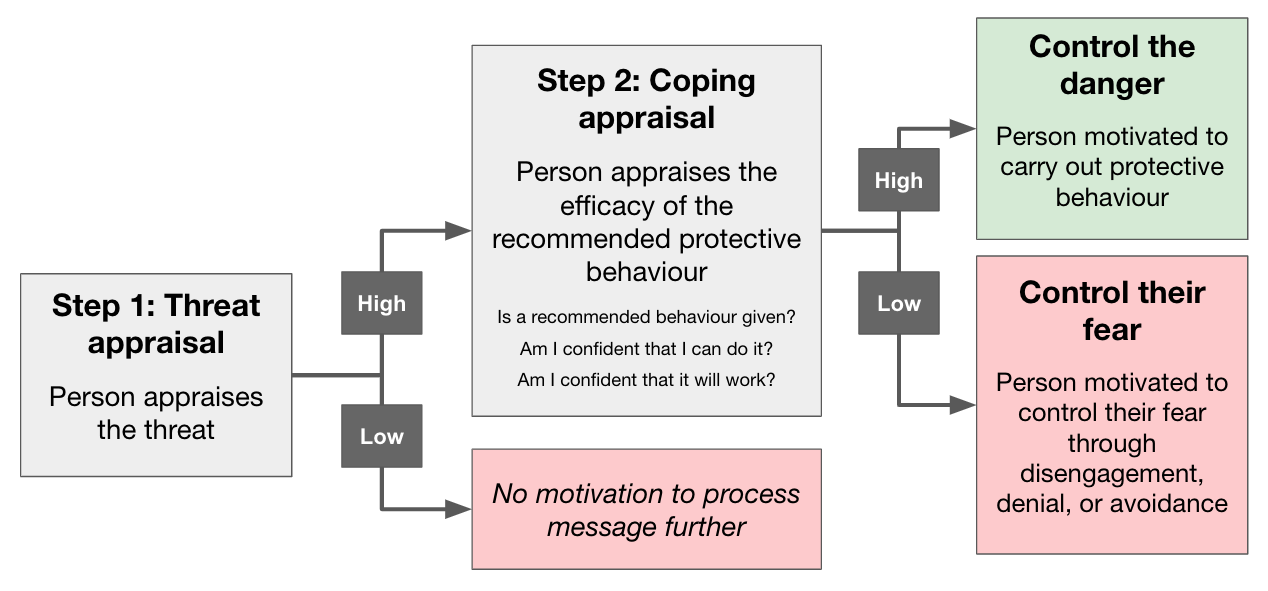

Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) explains how people make decisions in response to a perceived threat or risk (Reference 20). This theory shows us how to construct messages that will motivate people to take appropriate protective action.

How people respond to a threat

PMT sets out that people will only do the protective behaviour of interest (for example, giving up smoking, wearing a face covering, evacuating their home) if they both (1) judge the threat as relevant, and (2) believe that they can avert it successfully through their behaviour.

This is because people go through two steps after receiving a risk or threat-based message. This takes place even if the individual is not consciously aware of these thought processes.

Step 1: Threat appraisal

The person receives the message, and processes the information given about the risk or threat. They will appraise how likely it is, how severe it is, and how relevant it is to them.

If they perceive little threat (believing it is not likely, not severe, or not relevant to them) then they will not engage with the message further. However, if they perceive the threat as moderate or high, they will move to Stage 2.

What makes it likely that people will perceive a threat as high?

Specific research will provide the most accurate answer on how threatening audiences perceive certain events or risks to be, but there are some factors that make it particularly likely that people will perceive a threat as high.

Events that are hard to control, or that impact many people, or that have a particularly severe impact are sometimes known as “dread risks,” which people tend to view as highly threatening even if they are rare or unlikely. Examples include terrorist attacks, nuclear events, or plane crashes.

Other factors that influence people’s perception of threat include, amongst others:

- how physically close the event occurs to the person (with geographically closer events feeling more threatening than distant events)

- how immediate the negative impacts are (with immediate negative outcomes feeling more threatening than long-term outcomes)

- how established and well-understood the threat is (with newer and less-understood threats feeling more threatening than established threats).

If people appear to be underestimating the threat, it is worth highlighting some of these factors and what makes it potentially threatening to them personally, so that people act on the basis of correct knowledge.

Step 2: Coping appraisal

The person next appraises the efficacy of the recommended response. In other words, they appraise how able they feel to avert the threat through their own action. If they feel confident that they can carry out the recommended behaviour, and that the recommended behaviour will avert the threat, then they will be motivated to carry out that behaviour.

However, if they do not feel able to avert the threat through their behaviour (maybe no behavioural recommendation is given, or it sounds ineffective, or the person is not confident that they can do it), then that person will be motivated to reduce their fear, rather than carry out the protective behaviour. People may try to reduce their fear by disengaging, distracting themselves, or becoming avoidant.

Example: How people typically respond to threats

A Government campaign seeks to encourage the public to prepare for flooding with an emergency flood kit.

Step 1: Threat appraisal

People consider:

- what is the likelihood of flooding in my area?

- what are the potential consequences?

- how bad might the consequences be?

People who do not perceive flooding to be a significant threat will not process the message further, while those who do perceive a threat from flooding will move to the coping appraisal.

Step 2: Coping appraisal

People consider:

- how effective are flood kits in coping in a flood?

- am I able to prepare one?

- am I able to store it?

- will I be able to find it in the event of a flood?

People who are confident these behaviours will work and feel capable of doing them will carry out the protective behaviours.

People who are not confident that they will work, or do not feel capable of doing them, will attempt to control their fear instead, through avoidance or disengagement.

How can communications design effective messages about threats and risks, using Protection Motivation Theory?

The objective of applying PMT to communications about threats is to help translate awareness and assessment of risk into effective planning and preparation.

When planning communications to encourage people to engage in protective behaviours in response to risk, communications should:

- Help the audience recognise a threat and understand its severity, likelihood, and relevance to them.

- The message should be clear about what the risk or threat is and how likely it is, using language familiar and understandable to the audience. It should also help people understand their own level of risk, and how relevant the threat is to them.

- Help people feel capable of acting to reduce the risk.

- The message should clearly set out specific protective behaviours and explain how they will avert the threat. These behaviours should sound achievable, with specific instructions signposted if appropriate.

Example: How to enhance threat-based messages with insights from Protection Motivation Theory

This table gives some examples of threat-based messages. The left messages do not effectively apply insights from Protection Motivation Theory, while those on the right do.

| Weaker message | Stronger message |

|---|---|

| Flooding can be deadly. Stay vigilant and keep up to date with the latest advice. | There is a high risk of flooding in your area. Using this checklist makes preparing an emergency flood kit easy, and it can save your life. |

| Cycling without the right protective gear is dangerous. Responsible cyclists should wear a helmet at all times. | Urban cycling carries risks of head injury. A simple act of wearing a helmet cuts the risk of severe head injuries by half. |

| COVID-19 is a deadly disease, and the only way to completely avoid it is to stay at home. | Catching COVID-19 can have long-term health consequences. Wearing a face covering and letting fresh air in reduces the spread of the virus. |

About the table:

- Messages in the first column of the table are ‘weaker’ messages and do not effectively apply insights from Protection Motivation Theory.

- Messages in the second column of the table are ‘stronger’ messages and effectively apply insights from Protection Motivation Theory.

How can communications change public risk perception?

As communicators work on a developing crisis, there is a temptation to view the public mood with a ‘risk dial’ in mind, tailoring messages to either ‘hammer home the risk’ or ‘calm the public mood’ depending on current objectives.

However, the public doesn’t have a single ‘risk dial’. Risk is subjective, and responses to risk are influenced by individuals’ attributes and circumstances. Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) also tells us that making people perceive a higher level of risk will not necessarily translate into more action:

- if people feel like they are able to avert the threat through their behaviour (successful coping appraisal), a heightened perception of risk can lead to more action;

- however, if people feel unable to avert the threat, a heightened perception of risk can lead to disengagement or avoidance.

Given that different people have different risk perceptions and different perceptions of their capability to avert it, trying to universally ‘dial up’ the risk may well cause some to disengage. Furthermore, if the recommended response does not feel sufficient given the level of risk, some may result in engaging in their own (possibly maladaptive) ways of averting the threat or controlling their fears.

Conversely, trying to ‘dial down’ the risk might cause some of the affected audience to become complacent.

Making people feel confident that they can avert the threat through their behaviour can boost uptake of protective behaviours without necessarily changing audience risk perceptions. One way to do this is to make the behaviours clear and easy to carry out, for example by using clear instructions, checklists, or more extensive support.

That said, there are some cases in which it might be necessary to use communications to correct specific audiences’ risk perceptions, for example, if evidence suggests that certain groups are consistently under- or over-estimating their risk.

How can we help people develop a better understanding of the risks they face?

For groups that consistently under- or overestimate the levels of risk associated with a certain event or threat, communications can help people better assess their risk by telling them the likelihood and severity of the threat.

When designing communications about risk, it is useful to research the needs of the audience and their current understanding of risk, to ensure any communications can best meet those needs. Once communications are designed, ideally it should be tested with audiences.

General principles for communicating about risk

- Tell people the risk to the average person, alongside information about the risk to people within their specific audience group. For example, “For every 100 people who catch COVID-19, around 1 will die. For every 100 heavy smokers who catch COVID-19, around 6 will die.”

- Present information about risks in a clear and visual way that is easy for people to understand and process (Reference 23). For example, a statement like “Your risk of catching the virus within the next year is around 8%,” could be accompanied with a user-centred explanation, “In a crowd of 100 people with the same risk factors as you, it’s likely that around 8 will catch the virus in the next year”. This could be further enhanced with an ‘icon array’ graphic to illustrate what 8 people out of 100 looks like (Reference 24).

- If precise risk levels are not yet known, verbal probability estimates can aid public understanding. The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change defines verbal probabilities as follows:

- If the probability of occurrence is >99%, the verbal probability is defined as “virtually certain”

- If the probability of occurrence is >90%, the verbal probability is defined as “very likely”

- If the probability of occurrence is >66%, the verbal probability is defined as “likely”

- If the probability of occurrence is between 33%-66%, the verbal probability is defined as “about as likely as not”

- If the probability of occurrence is <33%, the verbal probability is defined as “unlikely”

- If the probability of occurrence is <10%, the verbal probability is defined as “very unlikely”

- If the probability of occurrence is <1%, the verbal probability is defined as “exceptionally unlikely”

- Communicators should use these terms consistently and carefully, appreciating that they may be interpreted differently depending on the context and audience.

- To bring risks to life for the target audience, case studies can be used to tell true stories of individuals that have been impacted by the relevant threat. Case studies of people facing similar risk factors can be more compelling and memorable than statistics.

However, the use of case studies can lead to disengagement, alarm, or psychological reactance if the case study is concerning or the audience feels they are being actively targeted. To reduce the chance of psychological reactance:

- case studies should always be accompanied by contextual information about general levels of risk and guidance on what people can do to reduce their own risk.

- case studies that focus on severe outcomes should be balanced with others that detail more moderate outcomes.

- use a range of messengers, including those that audiences perceive as part of their “in-group”.

Avoid ambiguity when communicating about evidence

It is common to hear scientists and leaders state that there is “no evidence” for a particular theory or claim, but phrases like this can be difficult for the public to interpret as its meaning is ambiguous:

- in some cases, “no evidence” that something is harmful is intended to reassure (for example, “there is no evidence that vaccines cause infertility.”)

- in other cases, “no evidence” that something is effective might be intended to simply remark on the absence of current data (for example, “we have no evidence that the vaccine is effective against COVID-19 transmission.”)

To avoid misunderstanding, communications should focus on promoting the right protective behaviour, rather than only describing the state of the evidence and leaving audiences to draw their own conclusions.

When encouraging behaviours, communicators should explain why that behaviour is recommended and demonstrate that the advice is trustworthy and based on the best available evidence.

If the scientific consensus has arrived at a particular behavioural recommendation (for example, that young women should get the COVID-19 vaccine), instead of saying “There is no evidence that the COVID-19 vaccine affects female fertility”, communications should instead clearly state the behavioural recommendation, and explain why scientists are confident that the advice is correct. (See, for example, the reassuring language used by Professor Jonathan Van-Tam in his public Q&A on 10 February 2021, in which he said he had never heard of any vaccine – let alone the COVID jabs – having an effect on fertility. The response is summarised in this BBC news article.)

A better message might read “Young women should get vaccinated against COVID-19 as soon as they are invited to. Leading scientists agree that the vaccine poses no risks to female fertility.”

How can we make the most of the public’s assistance?

The assumption that mass panic is a typical outcome of a crisis means that the public and their behaviour are typically framed as a liability in a crisis situation. Strategies may focus on how the public might be managed or controlled, and their behaviour restricted to prevent the so-called “mass panic”.

However, we know that a more accurate assumption is that the public are generally disposed to support and protect themselves and others. It is common for survivors to attempt to help each other in emergencies, and for the wider public to come forward to assist during crisis situations (Reference 6).

During the COVID-19 crisis 4,000 mutual aid groups formed representing 12 million volunteers who provided food, collected prescriptions and even walked dogs for those who were infected. Over 750,000 people signed up to be part of the NHS Volunteer Responders scheme in just 6 days, triple the scheme’s original target (Reference 21), and more than 540,000 people across the UK have volunteered in COVID-19 vaccine trials (Reference 16), representing an enormous mobilisation of public effort and time.

This tendency to help others and share resources makes the public a vital asset that can be harnessed to enhance disaster response, especially in crisis situations that hamper the centralised response, such as a cyber attack on vital infrastructure or a national power outage. This potential may be squandered if the public are prevented from helping one another, and central coordination can drastically increase the effectiveness of public efforts.

How can communications and policy makers facilitate an effective public response?

- Get communities, local authorities, and the public involved in crisis planning

- Draw on the expertise and experience of these groups when developing crisis management plans and guidance.

- Share crisis management plans where possible, making sure they are accessible

- Engaging the public in the government’s plans helps to build trust and establish clear expectations. Local groups and members of the public can identify potential gaps and contribute to problem-solving. It also enables advanced preparation.

- Provide central resources to support local coordination

- An effective public response relies on strong coordination and, ideally, motivated and experienced volunteers operating within established structures. While volunteering is often best coordinated locally, central tools, training, and resources may assist local areas in this effort.

- Identify any barriers to the public helping each other, and remove them

- Using the process set out in the section ‘What is behaviour, and why does it matter in a crisis?’, you can identify the barriers to the public helping each other. Use essential needs to anticipate where people may require support, and determine whether any barriers need removing.

- Use communications to promote community and national unity

- A shared social identity provides the basis from which people will feel motivated to help one another. Shared identities can be promoted by emphasising the shared experience of the crisis, and avoiding language that seeks to blame or divide.

- Provide clear direction on what the public should and should not do during the crisis.

- People will look to the government to provide direction on what to do to keep themselves and others safe. By providing clear guidance, the government can help people to respond in ways that contribute towards the overall response.

How can communications encourage compliance with guidance and regulations?

Public compliance with guidance and regulations is often essential for the success of a crisis response and for minimising negative outcomes. While it is often assumed that non-compliant behaviour will be widespread, prior crises show that the vast majority of the public will adhere to instructions and advice provided during a crisis.

That said, ongoing adherence is crucially dependent on the public’s perception of the legitimacy and fairness of the control measures in question, as well as their enforcement. Compliance is further enhanced when the government demonstrates respect and trust in the public.

How can we promote compliance with guidance and regulations?

- Provide clear communications on what action is required, and why (Reference 27).

- This reduces ambiguity and individual interpretation. Explaining why adds legitimacy to any instructions.

- Remind the public of their shared identity during the crisis to promote compliance.

- Research shows that when strangers become united against a common threat, they are likely to exhibit helping behaviours or altruism (Reference 28). Messages should therefore position the public as working together against the threat to promote compliance.

- Avoid excessively publicising that some are not complying to the rules, particularly if they are a small minority, as this may create the impression that non-compliance is widespread and viewed as normal, expected, or inevitable.

- Use ‘in-group’ leaders to deliver key messages.

- Research shows that adherence depends upon whether people see themselves and the authorities (or those delivering the message) as part of a common in-group. Using different messengers to reach different audience segments is normally an effective strategy. (Reference 30)

- Where possible, communicate ways in which people can overcome practical barriers to complying with rules (Reference 29).

- This might involve promoting support schemes that address financial barriers, or other initiatives that enable participation (for example, signposting people to vaccination centres with extended opening hours).

- When non-compliance is occurring, use available insight to determine the barriers to compliance and design communications accordingly.

- If people are facing legitimate practical barriers then increasingly stern communication may alienate and distress people rather than drive behaviour change.

- Ensure that advice and instructions are widely shared through different sources and messengers (Reference 27).

- Research on clean water has demonstrated that people are more likely to be compliant after viewing the same message from multiple sources. This may also reach audiences who do not consume mainstream news.

How can communications address non-compliance with guidance and regulations?

While the above can help promote compliance (or prevent non-compliance before it occurs) among the general public, what can communicators do to tackle non-compliance once it is occurring?

The ‘4 Es’ is a four-phase approach, developed by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) and the College of Policing (CoP) to address non-compliant behaviour. It is based on evidence that people are more likely to comply if they feel they have been treated fairly, have received an explanation, and have been given the opportunity to voice their point of view.

The first three “Es” (Engage, Explain, Encourage) are communication approaches, while the fourth (Enforce) is a last resort if communication fails to change behaviour. Authorities should foremost seek to encourage and persuade, to avoid psychological reactance (see the section ‘How can communications discourage harmful behaviour in a crisis?’) and loss of trust between authorities and the public.

How can communications discourage non-compliance with guidance and regulations?

1. Engage

Engage with the target group, take steps to understand their position, and demonstrate an appreciation of their opinions and perspectives. Showing sensitivity to the circumstances of non-compliant groups helps foster a sense of trust and constructive dialogue.

2. Explain

Gently highlight the rationale behind the guidance and regulations, to help people understand the logic behind rules and why their compliance matters (both for them personally and for broader society). Set out the risks posed by non-compliance, avoiding confrontational language that may alienate the target group.

3. Encourage

Encourage people to act in line with the rules, appealing to their social instincts, focusing on encouraging compliant behaviours, rather than challenging deeply-held beliefs. Be consistent and firm.

4. Enforce

If communications approaches fail, then the appropriate authorities will enforce rules using powers set out in the relevant guidance or regulations.

As a final note on compliance; while the above approach seeks to address non-compliance by promoting a dialogue of mutual respect, some instances of non-compliance and disorder may have deeper influences, with a crisis acting as a “flashpoint” for other negative sentiment and attitudes.

How can communications discourage harmful behaviour in a crisis?

Despite the tendency towards altruism in a crisis, difficult situations can have unpredictable effects on behaviour. People may react negatively to guidance and rules, and a small minority may engage in destructive or disorderly behaviour. Communication is one tool that governments can use to reduce harmful behaviour in a crisis.

How can we avoid negative backlash effects?

Hard-hitting messaging, rules, and mandates can sometimes backfire and lead people to actually do the opposite of the intended behaviour. When we feel that our choices are being restricted or our freedom is being threatened, we can respond by becoming defiant. The threatened option can become more appealing and enticing, and people may want to publicly display their opposition by visibly flouting instructions.

In other words, being told firmly not to do something can sometimes make us want to do it more.

This phenomenon is known as psychological reactance: people changing their thoughts, beliefs and behaviours to restore their sense of freedom in the face of externally-imposed restrictions.

Reactance can lead to:

- people taking action in an attempt to restore freedom (for example, by protesting against an instruction).

- defiance (for example, by publicly flouting an instruction).

- resistance to future persuasion.

What causes psychological reactance

Reactance can occur when people feel like an external force is limiting their options, threatening their personal freedom, control, or identity.

Generally, people feel most reactance when:

- the threatened freedom is perceived as important. We see more reactance toward vaccine mandates than mandated seat belt use.

- the threat feels significant and immediate. If a threat is immediate and has large consequences, you will likely see more reactance.

- they perceive the threat might escalate and limit further freedoms (slippery slope)

How can we design communications that minimise psychological reactance?

- Highlight choice.

- By highlighting options that people have, you avoid arousing perceptions that personal freedoms are being threatened.

- Provide people with information enabling them to make an informed choice.

- If your preferred policy option is beneficial to the individual or the public, stress this aspect in your messaging.

- Avoid language that might make people feel attacked or singled out

- Language that appears to demonise or shame people may induce a strong emotional reaction.

- Avoid using language that ties behaviour to moral or personal values

- Use expert and apolitical messengers.

- People tend to feel less reactance if they feel like the message comes from legitimate authorities with their best interests at heart.

Example: Messages that are more/less likely to cause psychological reactance

| More likely to cause reactance | Less likely to cause reactance |

|---|---|

| Strong threat to important freedoms: “If you don’t get vaccinated, you will be banned from some events.” | Enable informed choice: “It’s not too late to get vaccinated. Chat to GPs this weekend by ringing 191.” |

| Tying behaviour to moral or personal values: “If you care about others, wear your mask.” | Use neutral language: “Please wear a face covering in the building.” |

About the table:

- The table provides examples of messages in the first column that are more likely to cause psychological reactance.

- In the second column it provides examples of messages that are less likely to cause psychological reactance.

How can communications help maintain social order?

It is often assumed that a significant number of people will start behaving in a disorderly way as soon as a crisis hits, or that some will take advantage of it to commit criminal acts. However, studies simulating emergency scenarios (Reference 15) and studies of real emergencies (Reference 1) have found that the public will typically continue to follow social norms (such as queueing) and offer help to others (Reference 12). Understanding this, as well as what to do to both prevent and mitigate social disorder, is essential for communicators during a crisis.

How do you use communications to tackle looting and theft?

While looting and theft is frequently a concern of policymakers, studies of previous disasters have found that looting is rarely observed.

Media attention on minor incidents of looting and theft can make them appear widespread and increase public anxiety. Some incidents that are described or perceived as looting can sometimes have more innocent explanations, such as a victim’s family and friends salvaging possessions from their home (Reference 17).

In serious crisis situations, people may see no option other than to acquire food, water or other essentials without paying or seeking permission if they can’t meet these essential needs in other ways (Reference 7).

Overestimating the prevalence of looting has been shown to be highly consequential, and could even result in more deaths if people fail to promptly evacuate areas under threat, due to worry about the security of their belongings (Reference 22), or if inappropriate security at disaster sites prevents access by emergency responders (Reference 26).

How can we best communicate about looting?

- Communicate how people can meet their essential needs.

- For example, telling them where they can get free bottled water from.

- Explain the reasoning behind any observed “looting” to the public.

- If people are taking items or goods in a manner that may look like looting to the public, communications can explain what is really going on.

- Reassure the public that instances of violent or opportunistic looting are rare.

- Communicate that this type of looting is rare and only is only considered by a very small minority of people, despite media and public attention on these instances.

- Where looting is recognised as a risk due to difficulty in meeting essential needs, help businesses prepare (and/or assist).

- Examples include asking businesses to offer bottled water or other essential goods to people in an orderly manner, securing items of particular value, and providing simple mechanisms for people to “pay later” if card payment systems fail when they are trying to obtain goods.

How do you use communications to tackle excessive buying?

Excessive buying is observed in some crisis situations, as a way in which people try to secure access to goods in short supply, insulate themselves against future shortages, and gain a sense of control over challenging situations.

In most situations, excessive buying is quite rational and is driven by people responding to normal incentives. If an item is rumoured to be in short supply and is at risk of running out, then buying extra is a logical response to the situation from an individual’s perspective. It is rarely driven by extreme emotion or “panic” (Reference 31).

While incorrectly labelling this behaviour as “panic buying” and describing it as irrational may seem harmless, it can lead to inappropriate solutions. Policy makers may naturally focus their strategy on “calming people down,” and communicators may put out messages describing these buyers as “selfish,” leading to public frustration and sometimes exacerbating shortages.

How can we use communications to tackle excessive buying?

Don’t:

- Don’t tell people to “stop panic buying” or “calm down”

- Approaches that focus on “calming” people may fail to tackle the root causes of the issue. If people are rationally changing their buying behaviour to cope with unexpected situations, then trying to “calm” them will be ineffective (and messages exhorting people to “stop panicking” will likely create further impression of competition for goods).

- Don’t label buyers as selfish or immoral

- Addressing “selfish” buyers will unlikely cut through to audiences, as individuals will very rarely perceive their own buying behaviour as selfish. It is very easy to justify buying more than strictly necessary in order to feel more prepared and insulate against future shortages, and every person doing so will probably feel they have a good reason for their buying.

- Don’t single out certain groups as the cause of problems

- Blaming a “selfish minority” for excessive buying can create social tension and reduce people’s desire to help and support one another. If people feel that they are being singled out as selfish, this may lead to psychological reactance (defiance leading to a possible increase in undesirable behaviours, see the section ‘How can communications discourage harmful behaviour in a crisis?’).

Do:

- Set out what authorities are doing to resolve the situation and likely timescales, if known

- If shortages are expected to be temporary, communicate to help people form a realistic plan. If shortages are expected to last for a longer period, communicate to help people adapt their routines and habits accordingly.

- Tell people what they should do

- Give actionable advice, issuing clear guidance to the public about what behaviours they should stop, start, or change.

- Communicate often

- Update the public frequently, avoiding the appearance of an information vacuum, which might create opportunities for false information to spread.

- Reflect reality on the ground in communications

- Make sure that messages and information reflect the situation on the ground. Calming messages (“Don’t worry, supplies are normal”) that are subsequently disproven (for example, by social media posts of empty shelves) can exacerbate concern and prove damaging for trust.

How can communications maintain trust in a crisis?

During a crisis situation, it is particularly important to maintain trust between authorities and the public to ensure that people continue to trust official information sources and follow guidance and rules.

Trust is easily lost in a crisis, as information changes rapidly and government communication and activity will be under extra scrutiny.

Communications should aim to maintain public trust throughout crisis situations, and is central to rebuilding it when it is lost.

How can we maintain trust in a crisis?

In order to build and maintain trust, governments should act with competence, integrity, and benevolence, and should use communications to demonstrate to the public how it is doing so.

To demonstrate competence, governments should:

- show that decisions have been made on the basis of sound evidence and be transparent about uncertainties.

- set out a goal and a realistic plan to achieve it.

- show that citizen needs and perspectives have been considered.

To demonstrate integrity, governments should:

- show how decisions were made, and the reasons behind them.

- be open about failures and unknowns.

- show how they have acted consistently with their values and promises.

To demonstrate benevolence, governments should:

- show what it is doing to help and protect citizens.

- demonstrate that it acts fairly and compassionately.

Case study: COVID-19 pandemic

The assumption of panic

At the outset of the pandemic a number of assumptions were made about the public response to the pandemic. In the United States, politicians played down the risk of COVID-19 to “reduce panic”. Authorities in Denmark initially tried to make pandemic preparations outside public view to reduce the likelihood of “unnecessary fear.” (Reference 18) Similar assumptions about the risk of mass hysteria were held in many countries.

These assumptions turned out to be broadly false. In the UK, the public demonstrated a high level of adherence to restrictions, and chaotic scenes of mass panic did not generally materialise. By the end of March 2020, the movement of people in the UK dropped by an extraordinary 98%, far surpassing expectations. Analysis of compliance with COVID-19 regulations in the USA and Australia during the early stages of the pandemic revealed a “hitherto unprecedented level of adherence with public health emergency measures” (Reference 4), despite early concern that adherence would be low.

Stockpiling

In the UK, people with trolleys full of toilet paper and paracetamol were described as “panic buyers” in the media, implying that their actions were irrational and driven by excessive fear. This interpretation has been challenged by researchers who argue that in the circumstances – people concerned about being confined in their homes for an extended period, and empty shelves creating the perception that these essential goods were at risk of shortages – the behaviour can be understood as a relatively rational response, driven by a desire to be prepared rather than extreme fear (Reference 5).

Meeting essential needs

People faced a number of barriers to meeting their needs during COVID-19 restrictions in the UK. In particular, people who were self-isolating needed to find alternative ways of accessing essential supplies. Online grocery shopping and networks of formal and informal volunteers made it possible for people to get the supplies they needed without leaving their homes.

The majority of the workforce across countries were used to going into offices and other premises to work to earn a living. In the UK, businesses and employees in sectors that allowed for home working quickly adapted, with large sections of the workforce adopting remote working very rapidly at the start of the pandemic.

The UK Government offered self-isolation payments to people on low incomes who were asked to self-isolate but could not work from home, to limit the financial hardship caused by lost working days. In other industries that were not suited to home working, businesses rapidly adapted and put protective measures in place. It is also important to note that many people in essential industries and frontline roles, including transport, healthcare, and food supply, continued to work throughout the pandemic to ensure that the broader public could meet their essential needs.

People also had a strong desire to stay in touch with their friends and family despite not being able to do so in person. People met these needs by speaking over video calls, organising remote events and celebrating important occasions virtually. People developed other creative ways of substituting old social events for COVID-19 safe ones – some people spent more time outdoors, meeting people outside for walks whilst they could no longer meet in each others’ homes.

In the UK, the government made targeted exceptions to certain lockdown rules to help people obtain specific support from friends, family, or support services where they couldn’t meet their essential needs in other ways. For example, the support bubble system was created which allowed those living alone to join another household to form an extended household, meeting needs for emotional and practical support. People were also able to leave their household and join a new one to escape domestic violence or abuse, and those facing childcare difficulties were permitted to form “childcare bubbles” to meet their childcare needs.

It is important to note that the evolving nature of COVID-19 laws and guidance and the complexity of individual people’s circumstances meant that these exceptions, while very helpful for some, were not enough to fulfil all essential needs across the whole population. Some people were ineligible for “bubbles” or could not easily form them due to their circumstances, and many bravely persevered without targeted childcare or social support in unprecedented conditions.

Volunteering, co-operation, and altruism

The instruction to stay at home and high levels of COVID-19 infection created a major barrier to people meeting some of their basic needs, like accessing medicines and food. In March 2020, the NHS launched an initiative to sign up 250,000 people to its volunteer responders programme, and had to close the sign-up portal only 6 days later, after tripling this goal.

Many thousands more people participated in locally-organised voluntary groups, or volunteered informally to help neighbours access prescriptions, walk dogs, and deliver food. Despite minimal resources and the sudden onset of the crisis, these groups successfully coordinated effective support for the vulnerable and elderly in communities across the UK. In addition, more than half a million people volunteered to be part of vaccine trials.

Volunteers in many countries sewed face coverings at home, with some activity coordinated through groups like the “Big Community Sew” in the UK, and the “Army of Masks,” “The Masked Warriors,” and others in the USA and Canada.

Members of the public around the world played a vital role in the medical advancements required to tackle the pandemic, by signing up to participate in vaccine trials and then later in trials of therapeutics. Local pharmacies signed up to help deliver vaccines in the community and stewarding roles at vaccine centres were oversubscribed at many stages during the pandemic.

Use of Protection Motivation Theory to design effective messaging about threats

The most effective messages throughout the crisis made effective use of Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) by setting out the risk posed by COVID-19 and giving people a specific protective action to reduce this risk.

“Stay at home, protect the NHS, and save lives” was the key message in the UK’s first COVID-19 communications campaign, and set out a specific behaviour (“Stay at home”), and a clear purpose (“Protect the NHS, and save lives”) indicating that the virus posed a significant risk to the operation of health services. The message was initially presented by the Chief Medical Officer for England and the UK Government’s Chief Medical Adviser, but later assets showed this message being communicated by frontline staff in the NHS. Both messengers were highly trustworthy sources and adherence was correspondingly high.

The actions requested were also highly specific and were adapted over the course of the first lockdown in anticipation of potential triggers of drops in adherence, such as the bank holiday weekend (“Stay at home this bank holiday weekend”) and the heatwave that started around 6 weeks into the first lockdown when resolve to adhere may have started to wane (“Keep going at home”). All messages continued to outline the risk presented by COVID-19 and the action needed to reduce that risk (staying at home), in line with Protection Motivation Theory.

Threat appraisal: how do people experience risk?

Throughout the pandemic, polling conducted by the UK Government showed that belief that the risks of COVID were (or were not) exaggerated was a major determinant not only of how well someone understood the virus and how it spread, but also how likely they were to adopt the protective behaviours promoted in public health messaging.

It was clear from very early in the pandemic that those most at risk of serious illness and death from COVID-19 were elderly people and people with pre-existing health conditions that increased their susceptibility to respiratory illness. Later research also showed that people from all ethnic minority groups in the UK were at higher risk of mortality from COVID, with the highest risk faced by those from Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities, due to a combination of factors including health inequities, barriers to accessing healthcare, occupations, and household circumstances (Reference 9).

In the UK, those initially identified as being particularly vulnerable were issued letters before the first national lockdown informing them of their need to ‘shield’ (stay at home and avoid contact with others) to protect themselves. In general, these groups were much less likely to perceive that the risks of COVID were exaggerated. On the other hand, the group of the population who said that the risks were exaggerated tended to be younger on average, and statistically less likely to suffer severely from a COVID infection.

However, people’s risk perceptions were not only determined by their age, ethnic group, and other factors that affect susceptibility to COVID. It was well known that COVID affected individuals differently, and there were cases of young people and people with no known pre-existing conditions who had fallen seriously ill with COVID.

People therefore looked to their peers, as well as authorities, for cues about how concerned they should personally be. For example, when people observed other people in their social groups not wearing a face covering, they too were less likely to wear a face covering; people inferred, if my friend isn’t concerned enough to wear a face covering, why should I be?

Likewise, when lockdown rules were relaxed, this sent a strong signal to the public that the risks of COVID had decreased, and vice versa when rules were tightened. In the early days of the pandemic, prior to vaccination, COVID risk was linked to the level of community transmission which drove increased hospitalisation and death. Once vaccines reduced the link between COVID infection and these most adverse outcomes, and once mandatory COVID restrictions were removed in most countries around the world, the public lost this shorthand signal of COVID risk levels, making it more difficult for people to assess risk without doing their own research or relying on cues from their friends and family.

Avoiding psychological reactance

Millions of people around the world have been vaccinated against COVID-19. In countries where vaccine supply is plentiful, research shows that the decision to not be vaccinated was primarily driven by concerns around the efficacy and/or safety of the vaccine. Governments, charities, and health authorities have therefore exerted considerable effort to encourage vaccine hesitant groups to take it up through a mixture of public health messaging, expanding vaccine delivery options, and incentives. Some countries also implemented rules that made it more difficult to carry out normal activities while unvaccinated (for example, by requiring a negative test for unvaccinated people to enter certain venues, or banning unvaccinated people altogether).

Vaccination is commonly an emotive issue, and having the freedom to choose the healthcare interventions you accept is a highly important freedom. Hard-hitting and authoritative messages would therefore have run a serious risk of causing psychological reactance amongst the unvaccinated if people feel that these freedoms were at risk. Many of those who adopted anti-vaccine positions had genuine concerns around the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, and messaging that labelled these groups as foolish, selfish, or misinformed would have risked entrenching people in their position as they sought to defend themselves against attack.

Instead, UK messaging sought to create positive excitement around the vaccine and to direct people to sources of non-judgmental reassurance and advice if they had concerns. By making people feel that they had a choice and that their fears were being listened to and taken seriously, many of those who were initially sceptical eventually decided to take up the vaccine and anti-vaccine sentiment, while remaining present in some areas and groups, did not take off and pose a serious risk to the success of the programme at a nationwide level.

At a local level, some novel interventions were carefully targeted and delivered in a sensitive manner to further reduce the risk of triggering reactance. A GP practice in Leicester made targeted phone calls to people who had previously refused to be vaccinated, to offer to answer their questions and listen to their concerns, which were found to often be related to individual personal circumstances (for example, fear that the vaccine would negatively interact with a medication they were taking). Around 70% of those called proceeded to take up their first dose (Reference 32).

References

- Bowe, M., Wakefield, J. R., Kellezi, B., Stevenson, C., McNamara, N., Jones, B. A., … & Heym, N. (2021). The mental health benefits of community helping during crisis: Coordinated helping, community identification and sense of unity during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology.

- Clarke, L. (2002). Panic: Myth or reality?. Contexts, 1(3), 21-26.

- Cocking, C., Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2009). The psychology of crowd behaviour in emergency evacuations: Results from two interview studies and implications for the Fire and Rescue Services. The Irish Journal of Psychology, 30(1-2), 59-73.

- Czeisler, M. É., Howard, M. E., Robbins, R., Barger, L. K., Facer-Childs, E. R., Rajaratnam, S. M., & Czeisler, C. A. (2021). Early public adherence with and support for stay-at-home COVID-19 mitigation strategies despite adverse life impact: a transnational cross-sectional survey study in the United States and Australia. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-16.

- Drury, J., Carter, H., Ntontis, E., & Guven, S. T. (2021). Public behaviour in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: understanding the role of group processes. BJPsych open, 7(1).

- Drury, J., Novelli, D., & Stott, C. (2013). Representing crowd behaviour in emergency planning guidance: mass panic or collective resilience?. Resilience, 1(1), 18-37.

- Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2020). Crowds and collective behavior. In Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology.

- GOV.UK, (2010) Emergency Response and Recovery

- GOV.UK, (2021) COVID-19 Ethnicity subgroup: Interpreting differential health outcomes among minority ethnic groups in wave 1 and 2

- GOV.UK, (2021) Crisis communication, Government Communications Service

- Heide, E. A. (2004). Common misconceptions about disasters: Panic, the disaster syndrome, and looting. The first 72 hours: A community approach to disaster preparedness, 337.

- Mawson, A. R. (2005). Understanding mass panic and other collective responses to threat and disaster. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and biological processes, 68(2), 95-113.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of management review, 20(3), 709-734.

- Michie, S., Van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation science, 6(1), 1-12.

- Moussaïd, M., & Trauernicht, M. (2016). Patterns of cooperation during collective emergencies in the help-or-escape social dilemma. Scientific reports, 6(1), 1-9.

- NHS Digital, (2022) Coronavirus vaccine studies volunteers dashboard

- O’Leary, M., (2004). The first 72 hours: A community approach to disaster preparedness. IUniverse.

- Petersen, M. B. (2021). COVID lesson: Trust the public with hard truths. Nature, 598(7880), 237-237.

- Reicher, S., Drury, J. & Stott, C. (2020) The Truth About Panic. The British Psychological Society

- Rogers (1975) A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. The Journal of Psychology, 91(1), 92-114.

- Royal Voluntary Service, (2020) Findings from volunteers participating in the NHS volunteer responder programme during Covid-19

- Solnit, R. (2010). A paradise built in hell: The extraordinary communities that arise in disaster. Penguin.

- Spiegelhalter, D. (2019) The Art of Statistics. Pelican Books

- Spiegelhalter D. (2014) Using expected frequencies when teaching probability, Understanding Uncertainty

- Spiegelhalter, D. (2020 Communicating the coronavirus crisis, Plus Mathematics

- Tierney, K., Bevc, C., & Kuligowski, E. (2006). Metaphors matter: Disaster myths, media frames, and their consequences in Hurricane Katrina. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 604(1), 57-81.

- Vedachalam, S., Spotte-Smith, K. T., & Riha, S. J. (2016). A meta-analysis of public compliance to boil water advisories. Water research, 94, 136-145.

- Von Sivers, I., Templeton, A., Köster, G., Drury, J., & Philippides, A. (2014). Humans do not always act selfishly: Social identity and helping in emergency evacuation simulation. Transportation Research Procedia, 2, 585-593.

- Webster, R. K., Brooks, S. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). How to improve adherence with quarantine: rapid review of the evidence. Public health, 182, 163-169.

- Neville, F.G., Templeton, A., Smith, J.R. and Louis, W.R. (2021), Social norms, social identities and the COVID-19 pandemic: Theory and recommendations. Soc Personal Psychol Compass, 15: e12596.

- Ntontis E, Vestergren S, Saavedra P, Neville F, Jurstakova K, Cocking C, et al. (2022) Is it really “panic buying”? Public perceptions and experiences of extra buying at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0264618.

- Mohamoud, A. (2021). GPs convince 70% of patients who refused Covid vaccination to reconsider. Pulse Today

Acknowledgements

This guide was authored by Dr Laura de Molière, Abigail Emery, Sarah Jones, Dr Paulina Lang, Dr Moira Nicolson, Eleanor Prince, and Adrian Stymne.

This guide draws heavily from the work of academics in social psychology, statistics, and crisis communications, particularly the work of Professor John Drury, Professor Stephen Reicher, Dr Fergus Neville, Professor Sir David Spiegelhalter, Professor Clifford Stott, and other members of the Independent Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviours (SPI-B).

The authors would also like to thank colleagues who provided feedback on early drafts of this guide.