Strategic Communications: a behavioural approach

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points: 2

This guide sets out how to adopt a behavioural approach to ensure your communications are strategic.

Details

Contents

- Foreword

- About the approach

- Defining behaviour

- Policy context

- Objectives and audience insight

- Strategy and implementation

- Scoring and evaluation

- Further reading

- Acknowledgements

Foreword

Alex Aiken, Executive Director of Government Communications:

Behaviour change is fundamental to all government communications, regardless of discipline. Communications is not simply broadcasting the work of government after the fact. We are one of the vital levers government uses to realise its objectives and implement public policy. The success of that policy inevitably involves people starting, stopping or changing behaviours. That means our work must be focused on behaviour-based outcomes and insight.

This is why at the start of 2018 one of the eight challenges I set for government communications was for us to master the techniques of behavioural science. Effective use of behavioural science will allow us to deliver more effective communication activities at every stage of OASIS (Objective, Audience insight, Strategy, Implementation, Scoring/evaluation).

Based on rigorous academic research, we have taken some of the core principles of behavioural science and combined it with existing best practice across government into a simple and practical approach all government communicators can confidently apply to their work.

The GCS Professional Development Team provides further training and resources to support you in applying this content to your work – look out for details on the GCS website or through your own professional development team. These principles are not the beginning or the end of the commitment we must make to behavioural communications. They are the latest step of our collective journey to make our communications ever more outcome focused, insight driven and evidence based.

I’d like to thank all those GCS colleagues who have helped produce this guide and the wise counsel received from David Halpern and the Behavioural Insights team.

I look forward to seeing the approach set out here applied across government – and to more effective and audience-centred communication activities as a result.

About the approach

This document is for all government communicators and lays out how you can use a behavioural approach to ensure your communications is strategic.

Communications is one of the five levers government uses to achieve its aims and deliver public policy alongside legislation, regulation, taxation and public spending. Communicating strategically means using communications as such, directly aligning an organisation’s communications objectives with its policy objectives and HM Government’s priorities, and maximising the overall effectiveness of all the communications activities you run.

This is done through early collaboration with colleagues outside communications and involvement in the initial decision-making process. This ensures that as communicators:

- we contribute our expertise and audience insight to diagnosing policy problems;

- can advise on the most effective ways communications can help realise policy objectives; and,

- ensure when strategies are produced all available levers have been considered and the most effective combinations are chosen.

This document sets out an approach that allows you to do this in conjunction with the OASIS campaign model. It will show you how to:

- consider the policy context, identifying policy objectives in terms of behaviours;

- set objectives and use audience insight, using the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour) model to identify barriers to the desired behaviour and assess the best role for communicators so you can set communications objectives with clear links to the needs of the policy;

- use behavioural insight in your strategy and implementation through the EAST (Easy, Attractive, Social, Timely) framework; and,

- score and evaluate your communications activities in terms of behavioural outputs.

Most communication activities will have specific behaviours they are targeting but this approach is still useful where this is not the case. This is because it helps frame the question ‘why are the communications ultimately being done?’.

For example, all media and press teams frequently engage in reputation management activities. Reputation matters because it can become a barrier to the effective delivery of policy. If the public doesn’t have confidence in public health advice they will not respond to prompts for them to give up smoking, for instance. Good internal communications matters because it supports organisational effectiveness: for example, if employees don’t have confidence their views will be responded to, they won’t fill in staff surveys.

Even where you cannot identify clear behaviours to target, you can still examine what barriers you are proactively removing or reducing for colleagues.

Defining behaviour

A behaviour is an action that is observable – who does what, when and how?

A behaviour is not a change in attitude, being more aware of something, being engaged in something, a culture shift or a social norm. These are often important steps in getting people to the stage where they adopt the behaviour but are not your ultimate behaviour goal or outcome. They are a means but not an end.

Depending on the behaviour you want to see from your audience you will be trying to influence them to:

- Start or adopt a new behaviour such as joining the military or attending an internal training course;

- Stop a harmful behaviour such as drinking and driving or posting harmful content on social media;

- Continue or improve upon an existing positive behaviour such as paying your tax on time or remaining opted into your workplace pension;

- Change or modify an existing harmful behaviour such as drinking less alcohol or modifying abusive behaviours in a relationship; or,

- Refrain from taking up a harmful behaviour such as breaching new internal security regulations or becoming involved in knife crime.

Policy context

In order to set effective objectives for your communication activities you must make a clear distinction between policy objectives and communication objectives. Policy objectives set out the overall purpose of the policy. Communication objectives set out how you as a communicator will drive specific, identified behaviours that will help realise the wider policy objectives.

When considering the policy context, you must answer two questions:

- What policy objective will your activities support?

- How will people behave if those policy objectives are realised?

What policy objective will your activities support?

Begin by establishing the policy objective that your activities will support. Communication activities do not happen in a vacuum but are carried out to support the realisation of the government’s objectives. Policy objectives typically include:

- policy development;

- policy delivery; and,

- reputation management.

How will people behave if those policy objectives are realised? What behaviours need to be started stopped or changed?

You will then need to identify which specific behaviours are necessary to meet the wider policy objective. This needs to be done in collaboration with your policy and analytical teams as far as is possible so you understand the broader context you will be working in. Communications will have an important role in influencing those behaviours. But it will not necessarily be able to influence all of them, and it will work alongside other interventions for the behaviours it can help drive.

Example: Cutting childhood obesity

Policy objective

Halve the number of obese children by 2030

Policy objectives may be broad in scope with a long-term timeframe for implementation, as in this example.

Interventions to support delivery

There will usually be a number of interventions put in place to support the successful delivery of a policy. Each intervention will aim to change one or more specified behaviours and by doing so to contribute to the overall success of the policy objective. Communication activities will form part of the delivery plan for some or all of the interventions.

In this example, they might include:

- increased regulation of the food and drink industry;

- changes to advertising regulations to prevent harmful foods being advertised to children; and,

- getting children to exercise more.

Specify behaviours for each intervention

Taking each intervention, specific behaviours can be identified. For getting children to exercise more this could be:

Get primary school children to exercise for 20 minutes per day as part of their school day.

This behaviour is clear and specific and links to the intervention.

Objectives and audience insight

Having identified the necessary behaviours to meet the wider policy objective you can assess which of those behaviours communication activities can drive. This will form the basis of your communications objectives.

Do this by identifying barriers that might stop your target audience from engaging in those behaviours and then judging which ones communication activities will be able to help overcome. As some barriers can’t be directly overcome by communication activities alone this step helps you understand which of the behaviours you will seek to drive and set objectives on the basis of. It will also help you understand where communications will have to work in particular partnership with other teams to successfully overcome barriers.

The COM-B model helps you identify barriers in a systematic and effective way. It says that there are three conditions that need to be met before behaviour takes place. The barriers to overcome are anything that prevents those conditions being met.

Three conditions

Capability

Does your target audience:

- Have the right knowledge and skills?

- Have the physical and mental ability to carry out the behaviour?

- Know how to do it?

Opportunity

Does your target audience:

- Have the resources to undertake the behaviour?

- Have the right systems, processes and environment around them?

- Have people around them who will help or hinder them to carry it out?

Motivation

Does your target audience:

- Want to carry out the behaviour?

- Believe that they should?

- Have the right habits in place to do so?

For each condition, ask yourself and non-communications colleagues what prevents people from engaging in the behaviour and if there is any evidence already about the existence of these barriers. The questions will vary based on the behaviour you are working on.

We have provided examples of these questions on the next page. These are illustrated with answers for the previous example of getting primary school children to exercise more.

Capability

- Do they understand the issue?

- How barriers might be addressed: Tell them why it matters to them now and in the future in ways that resonate with them and those who influence them – teachers and parents

- Are they physically fit enough to do it?

- How barriers might be addressed: Ensure that different activities are available for different levels

- Are they able to understand what they should do?

- How barriers might be addressed: Provide clear directions on what they’re expected to do

Opportunity

- Do they have enough time to do it?

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Make it a compulsory part of the timetable so that head teachers put specific time into the day for exercise to happen

- Communicate benefits to teachers and head teachers so that they want to make time for the children to participate

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Do they have the right equipment to do it?

- How barriers might be addressed: Communicate benefits to teachers and head teachers so that they want to make time for the children to participate

- Is there space in the school for the activity to happen?

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Make exercise simple and ensure it can be done in uniform

- Create a programme that all schools can use

- How barriers might be addressed:

Motivation

- Do they want to do it enough?

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Create a system of rewards to encourage participation

- Make it fun

- Do they see the need to do it?

- How barriers might be addressed: Ensure that they’re reminded of why it’s important

- Can this be made into a habit?

- How barriers might be addressed: Ensure exercise takes place at the same time each day

- Do others around them encourage the behaviour?

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Encourage teachers and parents to support children to exercise

- Encourage children to motivate their peers

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Do they believe they can do it?

- How barriers might be addressed:

- Reassure them that exercise is for everyone

- Structure sessions so that everyone can participate at their own level and praise them for taking part

- How barriers might be addressed:

Once you have identified the ways communication activities can overcome barriers you can set your communication objectives. Summarise the roles that you’ve identified for communications in overcoming capability, opportunity and motivation barriers. In the example (cutting childhood obesity) the roles were:

Capability

Show children (and those who influence them – parents and teachers) why exercise is important and the benefits.

Opportunity

Make head teachers and teachers aware of the need to make time for exercise in the timetable (in this example, we’ll assume that there has been a change in policy).

Motivation

Encourage children to motivate their peers and parents and teachers to motivate children to exercise;

Reassure children that exercise is for everyone.

Before you finalise your communications objectives double-check that your proposed interventions will drive the desired behaviour and will be the most effective way to do so. For example, make sure you are confident that lack of exercise is not a minor contributor to childhood obesity compared to diets.

As always your objectives should be C-SMART: challenging, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant and timely. They should target the specific behaviour you have identified. For the opportunity barrier the communications objective would be X% of primary school head teachers agree to create 20-minute slots per school day in their school timetable for exercise.

Use insight on current awareness and understanding and knowledge gleaned from other campaigns to set meaningful targets. For more on how to set appropriate quantitative (or qualitative) targets for your communication activities, you can refer to the Evaluation Framework 2.0.

Before creating a communications strategy also state your overall audience. This should be as specific as possible. This will help you find the most relevant audience insight for your communication activities and ensure your strategy is as targeted as possible.

Ideas on how to ask the right questions and overcome the barriers

When you’re thinking about what questions to ask and how you might overcome barriers, draw on existing research and data that you or others hold. Ask your insight team, colleagues in policy or behaviour or data specialists in your organisation.

Communications and opportunity barriers

You will normally find the behaviour you are targeting faces barriers in all three conditions. Communications can only directly remove capability and motivation barriers, but if there are still significant opportunity barriers your communication activities are unlikely to drive behaviour change.

When identifying what barriers exist for your audience, any opportunity barriers you identify should always be fed back to your policy team. You can also examine whether communications can help indirectly remove opportunity barriers. Opportunity barriers for some might be related to capability or motivation barriers faced by others, which communications could then target. In the example, the school children’s lack of opportunity is not having the necessary time. This was addressed by motivating head teachers to change the school timetable so that children had the time they needed to exercise.

Strategy and implementation

A good communication strategy should contain:

- a clearly defined target audience (which you have already identified);

- a proposition;

- messages; and,

- a channel strategy

When creating a strategy you may need to segment your audience to maximise the effectiveness of your communication activities. This does not have to be done by demographics; it should be done by whatever distinctions within your audience make the biggest difference to how your communication activities are received. For example, when you are encouraging school children to exercise more the type of school they attend may matter more than their age.

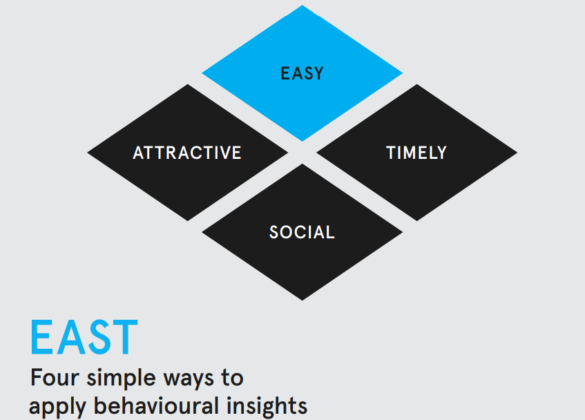

The EAST Framework

You can use the EAST framework to consider how your communication activities can overcome barriers and realise your communications objectives through your proposition, messages and channel strategy. Your communication activities should aim to make the desired behaviour:

- easy

- attractive

- social and

- timely where possible.

Of these, the most important is easy, and the one you should devote the most attention to.

When creating and implementing a communications strategy, you can ask yourself the following questions:

Easy

- Are you making the ask simple and straightforward, e.g. breaking bigger actions down into simple, concrete steps?

- Are you making the desired behaviour the default choice where possible?

- Are you requiring unnecessary additional effort to fulfil the ask, e.g. the number of click-throughs required on online adverts?

Attractive

- Does your communications attract attention from your target audience?

- Is it personalised?

Social

- Do a majority of people already engage in the desired behaviour? If so, can you demonstrate that to your target audience?

- Could people commit to the behaviour up front?

- Are you getting peers within your audience to advance your message?

Timely

- Are you communicating with your audience when they will be most receptive to your message?

- How immediate can you make the benefits of change?

- Can you get people to plan for future actions now?

When running communication activities that are in new areas or have large spends you should build pilots into your strategies. This will allow you to test your approach.

Your evaluation should begin as soon as you start implementing your strategy. This will improve your overall evaluation and give you the opportunity to iterate your campaign. Modern communications often allows for real time optimisation through a continuous process of adjustments in response to real time feedback and should be done where possible.

EAST: Four Simple Ways to Apply Behavioural Insights (Behavioural Insights Team website)

Scoring and evaluation

A full evaluation of any communication activities can only be completed once they are over but as already covered evaluation needs to be considered when you set your objectives and to begin as soon as implementation starts. Evaluation will ultimately tell you how successfully you have realised your original communications objectives; but you can test and evaluate various aspects of your campaign before or during their implementation.

It is important to establish a baseline for any numerical targets you set; this is where you would expect the metric to be with no interventions. In the example, the objective was X% of primary school head teachers agree to create 20-minute slots per school day in their school timetable for exercise. The baseline for this is the percentage of head teachers that would agree without any communication activities. A complete evaluation will be able to compare the outcomes with your objectives and with the baseline to establish what effect your communication activities had and how successful they were.

Good evaluation also serves as audience insight for future communication activities. It will provide evidence as to what behaviours people have and how they respond to your activities. This is particularly important if you regularly communicate with particular audiences.

The Evaluation Framework 2.0 provides more detail on evaluating communications activities, including recommended example metrics for inputs, outputs, outtakes and outcomes which we have reproduced here.

Further reading

- OASIS Campaign Guide

- Evaluation Framework 2.0

- The Behaviour Change Wheel – a Guide to Designing Interventions, by Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West (2014, Silverback Publishing)

- EAST Framework

Acknowledgements

This guide was written by Laura De Molière (DWP Behavioural Science Team) with Catherine Hunt (Cabinet Office), Lester Posner (HSE) and David Watson (DIT), with contributions from Nathan King (Cabinet Office) and Sarah Jennings and Pete Farrand (BEIS).

It draws on the work of Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West of University College London.

The authors thank colleagues across government for providing case studies and the rest of the DWP Behavioural Science Team, particularly Carla Groom, for their guidance.

- Image credit:

- The Behavioural Insight Team bi.team (1)