The Principles of Behaviour Change Communications

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points: 2

This guide, written by the behavioural science team at Cabinet Office, lays out how government communicators can use a behavioural approach to design and implement effective communications campaigns.

Contents:

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Objective setting

- Understanding your audience

- Capability

- Strategy

- Implementation

- Evaluation

- Acknowledgements

- References

Foreword

If there’s anything that 2020 has taught us, it’s that behaviour change is often the ultimate measure of campaign success. At the start of 2018, one of the eight challenges I set for communicators was for the profession to adopt behavioural science techniques to enhance the effectiveness of our campaigns. Coronavirus has made this challenge all the more urgent, and has demonstrated how communications is a powerful and flexible lever to create and sustain behaviour change.

The formation of the GCS Behavioural Science team has accelerated progress towards this goal of embedding behavioural science expertise across the Government Communication profession. Behavioural tools and techniques are now being used by communicators across government. This guide is the next step in that journey.

The guide brings together rigorous academic research and existing best practice to give communicators practical ways to apply behavioural science to their own campaigns. The accessible approach will help communicators learn how to systematically identify barriers to behaviour change, and use behaviourally-informed communications to overcome these barriers.

There is a lot more we can do, and this guide is just the start. The GCS Professional Development Team provides further training and resources to support you in applying the content of this guide to your work – look out for details on the GCS website or through your own professional development team.

I am very grateful to everyone involved in producing this guide and improving our practice in this area of our work.

I look forward to seeing the techniques set out here applied across government – and to building on our efforts so far in bringing behavioural science to the heart of campaign planning and implementation, to demonstrably improve our public service.

Alex Aiken

Executive Director, Government Communication Service

Introduction

This guide is intended for all government communicators and lays out how you can use a behavioural approach to design and implement effective communications campaigns.

All government campaigns should aim to make a difference. In this guide, you will find out how to apply a behavioural approach to campaign design and implementation to maximise the effectiveness of your campaign.

Behavioural science gives us the tools to analyse the context, empathise with target audiences, and ensure that the campaign helps enable behaviours. This guide will showcase the principles of behavioural change communications, providing theories and techniques to embed throughout a campaign in order to optimise its outcomes.

Following the success of the previous GCS guidance titled “Strategic Communications: a behavioural approach” and the demand for a more in-depth look into behavioural science for communicators, this guide expands on the previous content and provides practical tools and case studies to further support the application of behavioural science to communication activities.

How to use this guide

Throughout this guide, we will illustrate theory with case studies from the UK and international governments. We will also work through a fictional example campaign aimed at closing the gender gap in the Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) field.

For particularly complex campaigns, we recommend seeking advice from behavioural scientists during the campaign development process. Contact details are provided at the end of this guide.

Objective setting

Understanding the policy aims

One of the first steps in planning a campaign is setting campaign objectives. The communications objectives will need to be derived from a policy objective. The policy objective will always drive the campaign but, in order to achieve it, a combination of policy and communications objectives will need to be met along the way.

Example

Your objective could be “to increase engagement in sustainable behaviours”. The starting point is specifying what is meant by ‘sustainable behaviours’ and ‘engagement’. It could be that the focus of the policy is mainly on behaviours associated with energy use and that the definition of engagement will depend on the specific behaviour, for example installing solar panels or improving home insulation.

Here are some questions you may want to ask policy colleagues to understand the predetermined objective first:

- How was the policy objective selected?

- What is the wider intent and strategic context of the objective?

- Are there any other objectives or goals that might conflict with it? If so, what are the trade-offs?

- Is the stated objective based on what the decision-maker wants to see achieved, or an assumption about what the means to achieve it are (for example, a campaign)?

- What relevant evidence is available?

- Is there an existing user journey?

Defining the problem and key actors in the system

The next step in designing a campaign involves examining the current situation (meaning what is currently happening, what behaviours are we seeing) and defining what about it needs to change or happen as a result of the campaign.

Defining the problem also includes identifying the relevant ‘actors’ who are involved in behaviours relevant to the problem, which should help to identify the correct audience for your campaign.

For example, a campaign that aims to encourage children to eat more fruit may appear to address the problem that “children do not choose to eat fruit at school.” However, the actual problem may be that schools do not offer an affordable selection of fruit. In this case, schools may be a more suitable target for a campaign, as schools are the actor with the most influence on the outcome of interest.

In many cases, the “problem” may be obvious and require little further examination.

For example, a campaign that aims to reduce the use of single-use plastics addresses the obvious problem that too much non-biodegradable plastic waste is produced.

In other cases the problem may be less straightforward and could require exploring existing research or commissioning of new research in order to ensure that the problem is well understood, and that the relevant actors are identified.

For example, a campaign that aims to encourage people to apply to a university could aim to address the problem that there is a low number of applicants or the problem that certain demographic groups are overrepresented among applicants. Each problem would require a different communications approach.

Example 1: Problem diagnosis – identifying when the gender STEM gap first emerges

It is well documented that more men than women are in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) profession than women. Any campaign, needs to therefore reduce the gap between the number of men and the number of women in STEM fields. To fully understand this problem and identify where the campaign will be most effective, we need to understand when this gap first appears.

If we chose a point that is too late, the decision-making points for careers or necessary courses for pursuing STEM careers might have already passed. If we chose a point too early, the effects of the campaign might have ‘worn off’ by the time someone makes decisions that steer them towards STEM careers.

To ensure we chose the right age group, we can examine relevant literature to find out when the STEM gap starts to appear. Using desk research, we explored findings from a systematic review of the STEM gap in Europe conducted by Microsoft (see reference 1). The review shows that girls in Europe tend to lose interest in STEM around age 15. Therefore, a campaign that encourages uptake of STEM for children aged 5, or 25, is unlikely to have the desired effect.

School age children in the UK choose their A-level subjects around the age of 15. An analysis of A-level subject uptake split by gender conducted by Cambridge Assessment (see reference 2) (an exam board in the UK) shows that there is a gap in the choices of STEM subjects. Boys are approximately three times more likely to take physics and twice as likely to take maths and computing. This suggests that A-level choice is a key decision-making point in the closure of the STEM gap.

We can use this data (amongst others) to diagnose our problem; that girls tend to lose interest in STEM around the age of 15, and that A-level choices is a key point that widens the STEM gap in the UK. We can conclude that any campaign should focus on increasing the number of girls taking STEM subjects at A-level.

Given the context of the problem and the fact children cannot choose what they are taught, we can conclude that relevant actors in solving this problem are likely to be the child’s parents and teachers.

Mapping out behaviours with user journeys

Mapping out behaviours involves firstly identifying the key actions that the intended campaign audience needs to take in order to meet the policy objective. These actions can then be organised in the right order, recognising any interdependencies and connections between them, to create a user journey.

It is also a good idea to consider any actions required from others and incorporate them into the journey. This helps to see the full journey from the audience’s point of view and enables defining the target behaviours the campaign should focus on.

Thinking about how the audience interacts with their environment, and thus a campaign, could uncover potentially incorrect assumptions about how the audience will respond to communications.

User journeys serve as a necessary basis for creating a Theory of Change which will be covered later in the guide.

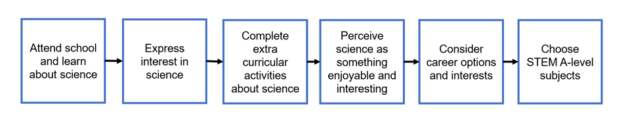

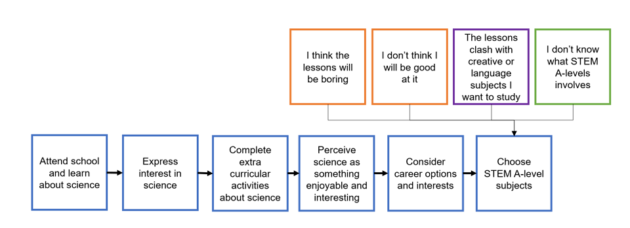

Example 2: Campaign to encourage STEM A-level subject uptake in girls

The first diagram depicts the user journey a school girl might go through when choosing STEM A-level subjects. It is likely that they will choose STEM subjects if they perceive science as for them, and find science lessons enjoyable and engaging. They may also complete extracurricular activities that further fuel their interest in science, such as reading books or watching documentaries. Each of these behaviours might have barriers attached to it, that we can overcome with different strands of our campaign.

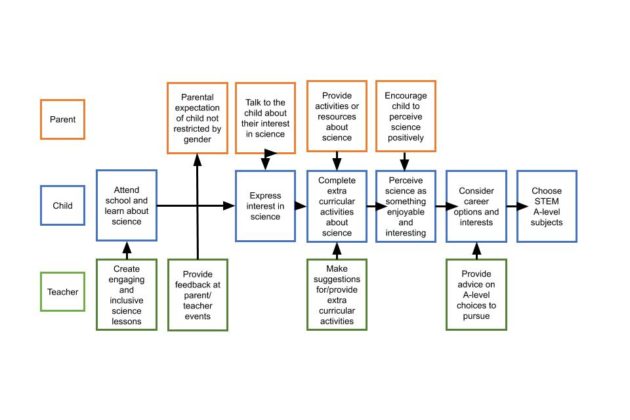

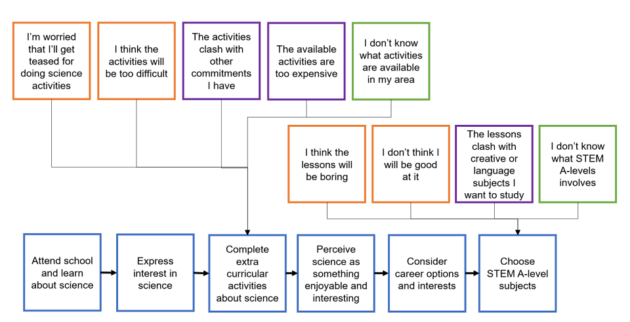

However, targeting the child might not be enough. When diagnosing the problem, we identified that because the child doesn’t have much decision-making power about what they are taught, other people surrounding the child may have to perform some behaviours for the campaign to be successful. We can then expand on the current user journey and create a map that shows the interactions required by the different actors in this scenario to help the child perform the behaviours in their user journey. An example of the behaviours required by the teachers and parents of the child are provided in the diagram 2 below.

As shown in the diagram 2 above, in order for children to learn about science, teachers need to create engaging and inclusive science lessons, which means they need to ask questions and demonstrate that science is a subject suited to both boys and girls.

If the campaign exclusively focuses on girls as an audience, then it is likely to be less effective if one of the desired behaviours relies on the actions of the teacher or parents.

Case Study 1: Hauliers drivers and border communications

After the UK’s departure from the EU, haulage vans coming to and from the EU will be subject to the same checks and paperwork requirements of the rest of the world. The behaviour change in the original campaign was a new requirement for hauliers of collecting and checking essential documentation from the supplier of goods they were transporting.

To understand what this behaviour change meant, we mapped the user journeys of hauliers, traders and managers under these new checks. This exercise unearthed a new interaction, whereby hauliers would have to decide about whether the paperwork they were given was correct. If it wasn’t correct they would have to refuse to drive with the goods. Interviews with drivers revealed that for a lot of them this interaction was complicated, difficult and intimidating due to language disparities and the drivers’ lack of decision-making power. Many said they would no longer drive to the UK if this interaction was required or, if pressured, drive knowing their paperwork was incorrect and risk being stuck at the border.

In addition, hauliers were attracted to the driving role because it required little interaction with others and minimal decision-making. This new interaction would require changes to their deeply embedded behaviours and identity in a short period of time if new checks were introduced. Based on this insight, we changed the campaign’s target audience to the haulier manager, whose role already involves dealing with paperwork, taking responsibility for others and making decisions. As a result, leaflets targeting drivers prompted them to call their manager when collecting goods, in order to transfer responsibility for this complex interaction to the haulier manager.

Setting campaign objectives

A good communications objective clearly sets out what the communications activity is intending to achieve and is informed by the relevant policy’s aims or organisational objectives. It should also focus on changing a specific behaviour or encouraging an action (an exception to this would be reputation building campaigns).

The SMART criteria are often used to guide the development of objectives and provide a good starting point.

Example 3: Developing objectives for the “Close the STEM gender gap” vision

- an example of a poor objective: ‘Get girls interested in science’

- an example of a better objective ‘Encourage girls to take up science subjects in further education (A-levels or equivalent)’

The first option makes for a poor objective because it’s not specific enough. ‘Interested in science’ could mean different things, for example going to a science exhibition, watching others engage in science, watching documentaries on the television, telling someone they like it. Some of these behaviours will help to meet the policy aim, but do not give defined, measurable outcomes to be tested against the objective.

The second option is better as it includes a discrete observable action that one can measure, for example number of girls choosing science subjects for A-level, and one that contributes to the likelihood of closing the gender STEM gap.

Understanding your audience

As all communicators know, clear instructions are not always enough to drive behaviour change. Audiences may face considerable other barriers to enacting the desired behaviour.

This section will introduce you to the COM-B model. The COM-B model explains what conditions are required for behaviour change to occur, and provides a framework for understanding and exploring the barriers to behaviour change that audiences might face.

Understanding barriers to behaviour change using the COM-B model

According to the COM-B model, in order to do a behaviour an individual must have the Capability to do it, the Motivation to do it, and external factors must provide the individual with an Opportunity to do it (see reference 3).

Capability

Capability is defined as an individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned (see reference 3). In communications, it typically refers to the audience having the awareness, knowledge, and skills to enact the intended behaviour.

A “capability barrier” occurs when a person cannot enact a behaviour due to not possessing the necessary awareness, knowledge, or skills. Campaigns that intend to encourage behaviour change by promoting awareness or providing educational information will typically be aiming to address capability barriers.

Generally, capability barriers may be the easiest to address using communications – it feels like the natural job of communications to inform and educate audiences.

To find capability barriers to the desired behaviour, these questions may be helpful:

- Is the audience aware of the issue or the need to change behaviour?

- Does the audience have the right knowledge to do it?

- Does the audience have the right skills to do it?

- Is the audience physically and mentally able to do it?

Motivation

Motivation is defined as “all those brain processes that energize and direct behaviour, not just goals and conscious decision-making…[including] habitual processes, emotional responding, as well as analytical decision-making” (see reference 3). It is helpful to think of motivation as the beliefs and attitudes that drive enthusiasm, or lack of it, to enact a behaviour.

A “motivation barrier” occurs when a person does not enact a behaviour due to not wanting to do it, or not believing that they should do it. Campaigns that intend to encourage behaviour change by evoking emotion, highlighting risks of inaction, or changing opinion about the importance of a behaviour will typically be aiming to address motivation barriers.

Habit is also a determinant of motivation, in the sense that if someone habitually enacts a behaviour, they are unlikely to require much further motivation to continue to do so. So if habits are firmly in place among the target audience in line with the target behaviour, they are unlikely to face motivation barriers to that behaviour. If the audience has other habits that might make it more difficult to enact the desired behaviour, then this may negatively impact motivation.

Motivation barriers can be addressed using communications, to encourage people to change their beliefs or attitudes towards a behaviour.

To find motivation barriers to a desired behaviour, these questions may be helpful:

- Does the audience believe they should do it?

- Does the audience want to do it?

- Does the audience have habits in place to support it?

Opportunity

Opportunity is defined as “all the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it” (see reference 3). In practice, this will refer to things like having the time, resources, tools, money, and access to enact the desired behaviour.

An “opportunity barrier” occurs when a person does not enact a behaviour due to something outside their control – for example, lacking the money to pay a fee for a service, or lacking access to a computer to use an online tool.

Typically, communications alone cannot easily address opportunity barriers, as these sit outside the control of the audience. This is why it is particularly important to explore opportunity barriers, as a campaign alone will not be sufficient to remove these barriers and drive behaviour change.

To find opportunity barriers to the desired behaviour, these questions may be helpful:

- Does the audience have the resources to do it?

- Will the system or environment allow the audience to do it?

- Will the audience’s social and physical environment help or hinder them in doing it?

Removing opportunity barriers: options for communicators

While communications cannot easily address opportunity barriers, there are two ways that communicators may be able to adapt campaigns to remove these barriers in other ways.

Shifting the target behaviour

It may be possible to remove opportunity barriers by changing the target behaviour of the campaign. For example, if a campaign aims to encourage park users to throw their litter away correctly, the audience may face the opportunity barrier that there is no nearby bin. A campaign could instead aim to encourage park users to take their litter home with them, removing this opportunity barrier.

Shifting the target audience

Some opportunity barriers may be caused to capability or motivation barriers faced by people outside the target audience, which communications could then target.

For example, if a campaign intended to encourage children to eat more fruit at school, the children may face an opportunity barrier of there being no fruit available – which cannot be addressed by a campaign. However, this opportunity barrier (lack of fruit) may be caused by lack of motivation from a headteacher to provide fruit.

Motivation barriers can be addressed by communications, therefore the campaign could instead aim to motivate headteachers to provide fruit at school.

Applying COM-B in practice

Once the objective of a campaign is defined, the next step is to identify which barriers the audience might face. The COM-B model can be used to provide useful structure and prompting for this exercise.

This task requires communicators to put themselves firmly in the shoes of the target audience, and try to view the world from the audience’s perspective. What might stop the audience acting? What difficulties and pressures might they face?

Make sure that you consider barriers across all three COM-B categories – Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation.

Questions to prompt “Capability” barriers

- Is the audience aware of the issue or the need to change behaviour?

- Does the audience have the right knowledge to do it?

- Does the audience have the right skills to do it?

- Is the audience physically and mentally able to do it?

Questions to prompt “Motivation” barriers

- Does the audience believe they should do it?

- Does the audience want to do it?

- Does the audience have habits in place to support it?

- Are there any consequences if my audience doesn’t do it?

Questions to prompt “Opportunity” barriers

- Does the audience have the resources (time, money, access, tools) to do it?

- Will the system or environment allow the audience to do it?

- Will the audience’s social and physical environment help or hinder them in doing it?

These questions should help communicators produce a long list of barriers that might prevent a person changing their behaviour in the way that the campaign intends.

At this stage, the list can be long, and you can make some guesses and assumptions.

Further barriers can be identified using:

- Existing research

- New research, particularly if it is an unusual subject or a hard-to-reach audience

- Third-party research or other published findings

- User research with members of the target audience

- Gathering views from colleagues and stakeholders

Example 4: Campaign to encourage girls to take up STEM subjects at school

As a girl choosing my A-level subjects, I might not choose STEM subjects because…

Capability (awareness and knowledge)

- I don’t know what STEM careers are available

- I don’t know what it involves

Opportunity (resources and processes)

- The lessons clash with creative or language subjects that I want to study

- The lessons move too fast for me as many classmates have prior knowledge

Motivation (beliefs and attitudes)

- None of my friends are doing it and I don’t want to be on my own

- I think the lessons will be boring

- I don’t think I would be good at it

The next step is to use research and evidence to validate the hypothesised barriers, and to work out which barriers are likely to be the most significant and widespread.

This can be achieved using a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods, including polling of the target audience, structured interviews, and focus groups.

The outcome of this step should be a refined list of barriers categorised under the COM-B categories, and communicators should have a clear idea of which of the identified barriers are likely to pose the most significant obstacles to behaviour change.

In our worked example 5 below, imagine that we have conducted interviews and polling with girls choosing their A-level subjects, and have identified the barriers marked with an asterisk as the most significant.

Example 5: Campaign to encourage girls to take up STEM subjects at school

As a girl choosing my A-level subjects, I might not choose STEM subjects because…

Capability (awareness and knowledge)

- I don’t know what STEM careers are available

- *I don’t know what it involves

Opportunity (resources and processes)

- The lessons clash with creative or language subjects that I want to study

- *The lessons move too fast for me as many classmates have prior knowledge

Motivation (beliefs and attitudes)

- None of my friends are doing it and I don’t want to be on my own

- *I think the lessons will be boring

- *I don’t think I would be good at it

The final step is to determine which barriers can be influenced by a communications campaign, and which will require other policy interventions.

As a general rule, communications can typically only influence capability and motivation barriers. Opportunity barriers (resources and processes) are unlikely to be influenced by a communications campaign. In other words, a campaign can address knowledge and understanding (capability) and beliefs and attitudes (motivation) but cannot typically address a lack of resources, tools, or money, or access.

If the analysis has identified significant opportunity barriers to behaviour change, then it is possible that a campaign may not be effective in changing behaviour. If the audience will face significant opportunity barriers, then it may be useful to explore what interventions or changes could remove these barriers.

The final product should be a list of confirmed barriers to behaviour change that can be effectively addressed by a campaign.

Case Study 2: Modern Slavery

There are approximately 10-13,000 potential victims of modern slavery in the UK. In 2019, following an audit of existing communications, the National Security Communications Team (NSCT) within the Cabinet Office identified a need for communications activity to prevent and protect individuals at risk of modern slavery.

Initial campaign objectives were:

- Reduce the number of people who are forced into modern slavery in the UK by informing them and the community of modern slavery risks and signposting them to the Modern Slavery Helpline.

- Increase reporting of suspected modern slavery among frontline staff.

- Increase understanding of the issue of modern slavery among the UK public.

Problem diagnosis revealed that that frontline professionals provided key touchpoints for victims of modern slavery, and were more likely to come into contact with victims on a regular basis. Three priority sectors identified were banking, healthcare, and recruitment. The campaign focused on the ‘empowered bystanders’ as the primary audience. Individuals working in these roles were interviewed to identify what barriers they felt were present in preventing them reporting a case of modern slavery. Details of the barriers are provided below.

Capability (awareness and knowledge)

- Able to spot signs but not necessarily making the connection to modern slavery

- Not in the front of their minds to spot

- Feels distant and not something they have considered

- Reporting mechanisms unclear

Opportunity (resources and processes)

- Time pressured jobs

- Some professionals are not allowed to use their phones whilst on duty

Motivation (beliefs and attitudes)

- Fear of getting it wrong, feel like they need comprehensive evidence

- Don’t want to look like they are stereotyping

- Don’t always feel like it is their place to be involved in other’s business

Communications cannot overcome the identified opportunity barriers as they cannot give people more time in their day to day work, or overcome company policy which does not allow phones to be used. However, the campaign can address capability and motivational barriers by creating transparency around reporting mechanisms, and reassuring people that they are doing the right thing when they are reporting.

As a result of this COM-B analysis, a key behaviour change was identified. Most professionals were aware of the signs, but did not feel empowered enough to act on said suspicions by phoning the help line. The campaign therefore aimed to get these frontline professionals to look out for, and feel comfortable reporting, incidents of modern slavery by phoning the Modern Slavery Helpline.

A key channel used to reach frontline professionals was out-of-home billboards in high footfall areas across transport hubs. A digital-on approach was taken with advertising on Facebook and Instagram, as well as a bespoke Spotify advert for three music genres. This helped reach audiences at multiple stages throughout their commute and during their usual working day.

Sector-specific campaign materials were made for each profession of the signs to look for, allowing them to identify themselves in the campaign and therefore recognise their role in the prevention of modern slavery. The language used informed frontline professionals what they should look out for and reassured participants that it would be doing the right thing to do.

As a result, frontline professionals said they felt better equipped to identify modern slavery in day-to-day work, and recognised that the campaign was helping them to spot a difficult type of vulnerability to categorise. The campaign evaluation additionally found that the behavioural change objective was achieved. Evidence from the Prime Minister’s Implementation Unit revealed that a significant and meaningful change in the volume of referrals to the helpline was directly attributable to the campaign. Evaluation of the London-specific phase showed that 234 referrals can be directly attributed to the campaign, totalling 507 potential victims lifted out of exploitation since the launch.

Articulating your assumptions about behaviour

Assumptions are thoughts about other people or things accepted without having the evidence to know they are true. They are formed by individual beliefs and values, professional experience, organisational values, and influenced by particular intellectual traditions and analytical perspectives. Assumptions range from ideas around the context, the drivers of change, the cause-effect relationships between interventions, outcomes and context, as well as individual and organisational values.

For example, when developing a campaign tackling smoking cigarettes, it might be an assumption that smokers are not aware of the poor health outcomes associated with smoking, and design a campaign to address the assumed knowledge gap. But what if this assumption is not true? The target audience may smoke in order to break up their working day or socialise with their friends while out, despite being aware of the negative effects on their health.

Despite the risk associated with making assumptions, articulating them is often a necessary first step to finding out what is truly driving or preventing a behaviour. Identifying your assumptions early on in the campaign development process means they can be explored to make sure the campaign is not based on assumptions that are not supported or not fully supported.

Assumptions can be tested either through primary research (for example, commissioning a survey, conducting focus groups or interviews) or by appraising academic evidence in a literature review. Evidence can be used to check and challenge specific assumptions, unearth new ideas and concepts, broaden the range of strategic options that may be relevant for the context, and strengthen their quality to provide a confident basis for action.

Example 6: Assumptions about gender and STEM

The list below shows examples of potential assumptions that could be made about gender and STEM. It also shows selected pieces of evidence, which either support or don’t support the assumption.

Please note the evidence examples used below were selected for illustrative purposes only and do not substitute for a review of available evidence.

Assumption: Most women are not interested in STEM.

- Evidence example: 42% of girls surveyed by Microsoft would consider a STEM-related career (see reference 1) – assumption supported

Assumption: Having great math skills makes girls more likely to obtain a science degree.

- Evidence example: Girls with high math skills but little interest in a STEM career are less likely to pursue a science degree than those with average math skills and high interest in science (see reference 4) – assumption not fully supported

Assumption: Females with successful STEM careers can act as influential messengers

- Evidence example: Research has shown that female role models can positively influence women’s attitudes toward STEM careers (see references 5 and 6) – assumption supported

Assumption: Parents have a role in encouraging STEM uptake in women and girls.

- Evidence example: Parents who believe that boys find math more useful and important than girls were found to rate their sons’ math ability higher than daughters’ math ability. These beliefs were positively associated with children’s own perceptions of their ability (see references 7 and 8) – assumption supported

Assumption: Studying STEM subjects is desirable because it increases employment prospects compared to HSS (arts, humanities and social science).

- Evidence example: The 2017 Labour Force Survey shows that 88% of HSS graduates and 89% of STEM graduates were employed in that year (see reference 9) – assumption not supported

Conclusion:

Whilst some of the above assumptions are supported by evidence, the assumption that taking STEM subjects increases employment prospects is not. We should therefore be careful not to use this assumption to inform our campaign, as it will not increase the likelihood of behaviour change.

Strategy

Strategy is a plan of action designed to achieve an overarching goal. When creating a good communication strategy it is important not only to consider how the planned communication activities will help overcome barriers to behaviour change but also whether there may be any unintended consequences that should be considered as part of the strategy.

Unintended consequences

What are unintended consequences?

Unintended consequences can be described as outcomes of a campaign that are not intended or foreseen. Sometimes these consequences can be positive, such as campaigns that aim to increase physical health having a positive spillover effect on mental health. However, unintended consequences can lead to adverse impacts which may undermine the overall success of the campaign. Unintended consequences can present themselves in many different ways, and this section will take you through a few examples.

Target Audience Behaviours

This occurs when the target audience adopts a behaviour that the campaign did not promote. For example, you may run a campaign to reduce the number of fizzy drinks young people consume to improve their dental health. Campaign evaluation shows a reduction in the number of fizzy drinks purchased by young people. However, there is an increase in drinks that have a high fat content, such as milkshakes. This may improve dental health but have an adverse effect on other health outcomes, leading to a mixed and unpredictable impact on overall health.

Other audience behaviours

This occurs when a campaign leads to unintended behaviours from actors outside the target audience. For example, a campaign designed to stop young people from binge drinking might show a group of people at a house party drinking copiously, with a warning about the health risks. However, such a campaign may unwittingly make such a scenario look appealing or exciting, leading some of the target audience to view binge drinking in a positive light and undermining the success of the campaign (see reference 10).

Unintended outcomes

This occurs when the target audience performs the behaviour you ask them to, but in doing so falls victim to adverse outcomes. For example, you may run a campaign to reduce air pollution in a city by encouraging people to cycle to work. However, if safety measures (such as road safety training or protective equipment) are not in place, an unintended outcome might be more road traffic accidents involving cyclists.

Operational consequences

This occurs when a campaign creates additional or unexpected demand on an organisation or support services, leading to knock-on effects on operational delivery. For example, a campaign may launch to alert people to a new travel pass. If the instructions to obtain this pass are unclear or difficult to understand, audiences may choose to telephone a service centre for help, which may not be equipped or resourced sufficiently to cope with the additional demand.

Case study 3: ban the box campaign

‘Ban the Box’ was an initiative in the US aimed to reduce the influence of criminal records on hiring practices, and increase the employment prospects of those that had just left prison to prevent re-offending. However, the absence of this information led hiring managers to make assumptions based on the characteristics of the applicant and who they expected to have a criminal record. The campaign did not consider the perspective of employers on hiring ex-offenders. As an unintended consequence, this campaign led to a reduction in the employment prospects of Black and Hispanic men (see reference 11).

Example 7: Gender and STEM – gender and reading?

Imagine that as a result of the time we dedicated to overcoming barriers and designing behaviourally relevant solutions to them, we have increased the number of females taking STEM subjects to A-Level. However, let’s say we revisit this age cohort in a few years to see if the campaign has lasting effects. We find that there are still far more men than women in STEM related careers. What could have happened? Was our campaign a failure?

Examining potential unintended consequences might help to find out. It has been documented that in more gender equal societies, girls and boys perform about the same in maths, but girls are much better at reading than boys (see reference 12). This means that in such societies, girls have the option of going into both STEM-related fields, such as engineering, and reading-related fields, such as law (see reference 13). Boys however, can only pursue STEM related subjects, so the gap will likely persist. Therefore, we didn’t acknowledge that the STEM gap was partially accounted for by a reading gap, leading to a reduction in choice for one gender but not another.

If we were to re-do the campaign, we might therefore add a strand that explores gender and reading, and then removes barriers for boys pursuing more arts-based careers alongside gender and STEM.

How can I reduce unintended consequences?

Given the complexity of many government policies and, by extension, campaigns it is difficult to predict and identify all possible consequences. However, the following tools can help you uncover and mitigate some potential consequences.

- User journey mapping can uncover hidden steps that your audience may have to go through in order to achieve the required behaviour change, this helps to design communications to address each behavioural change so your audience does not fill in the gaps themselves.

- Identifying barriers using COM-B allows you to understand what will contribute to your audience(s) making decisions or enacting behaviours. Having a full understanding of this means you can systematically remove barriers to behaviour rather than have some remaining and contributing to unintended consequences.

- Carrying out research and ethnography means you can directly engage with the audience of your campaign, understand what their lives are like, and how they make meaning from different behaviours in the world. Speaking to a diverse group of your target population will give you an understanding of how they would act in response to your campaigns to avoid unintended behaviours.

- Articulating your assumptions using theory of change is a powerful tool for mitigating unintended consequences and being explicit about how your campaign will work. You can articulate potential risks and how you will monitor them, and mitigate their impact.

Theory of change

One of the most effective things you can do to avoid unintended consequences is to map all of the planned communications activity and assumptions using a theory of change.

A theory of change is a method used to illustrate how and why behaviour change is expected to happen in a particular context. It maps out all of the factors that will influence an individual’s or organisation’s likelihood of undertaking a particular behaviour.

This technique allows you to articulate the parameters of your campaign, by distinguishing the role of opportunity barriers in preventing behaviour change. It also allows you to understand the context in which your campaign is operating in, to set realistic expectations about how people will behave.

We can construct a theory of change using COM-B and a user journey, as outlined in the template diagram below. In this map, all of the behaviours our audiences are expected to do, and their respective barriers, are made explicit. This allows our assumptions about how the campaign will work to be transparent, and be tested with stakeholders and the audience.

Mapping the interactions between barriers to each behaviour additionally means that evaluation questions can be assigned to each barrier, thus enabling the communicator to track which barriers are most prominent, and which are being overcome by the campaign. The campaign’s strategy can therefore be adapted to the changing needs of the audience, increasing the likelihood of behaviour change.

Example 8: Women in STEM

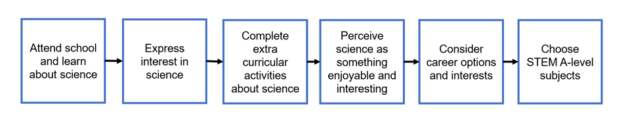

Now that we have constructed our user journey and identified COM-B barriers, we can combine these into a theory of change, assigning each barrier to a behaviour on our journey and mapping how barriers influence each step in the journey.

We start with the journey for the child constructed earlier in this guide:

We then add the barriers we have identified for the behaviour of ‘Choose STEM subjects at A-Level’. Capability is shown in green, opportunity in purple, and motivation in orange.

This process can be repeated for the other behaviours in the user journey to understand how barriers earlier in the process can lead to a reduction in behaviours change later in the user journey.

We can do this for all the audiences and behaviours identified in our campaign to create an overall theory of how we think the campaign will work. We can use this framework as a basis for multi-stranded strategies and making sure different audiences targeted in the campaign complement each other. We can also use this framework to design evaluation questions to see which parts of our campaign are working, and which need adapting.

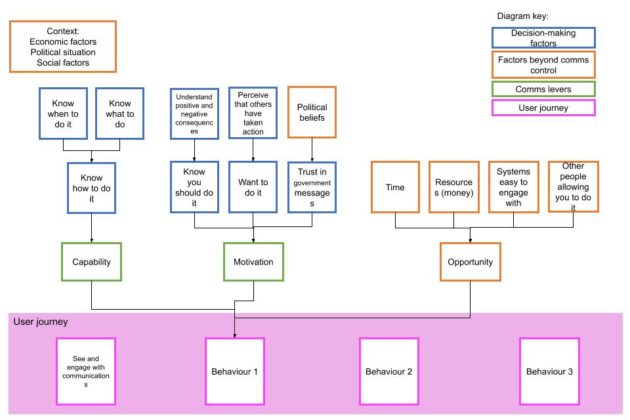

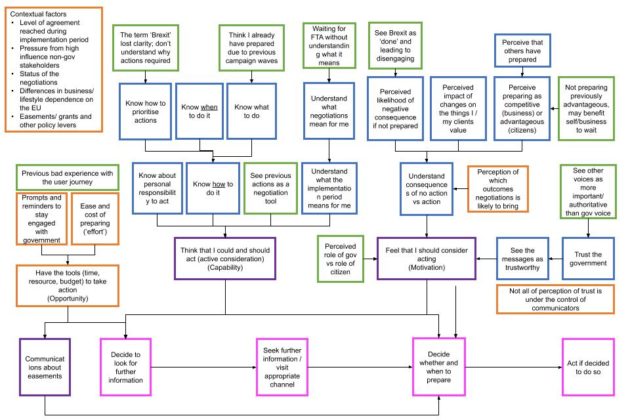

Case study 4: EU Exit transition campaign

This example is a particularly complex Theory of Change, to illustrate how this approach can successfully be applied to large-scale campaigns.

Businesses were an important audience for the EU transition campaign, as their preparation and state of readiness were essential in a smooth departure from the EU on 31 December 2020.

To ensure we understood the cognitive challenge faced by businesses before the campaign launched, we developed the EU Transition Theory of Change. As the campaign consists of many actions required of a vast and varied audience, the theory of change had to match the complexity of the campaign. This theory of change consists of a map of the decision-making journey an individual must take between seeing a “Get ready for Brexit” message and taking action (pink boxes at the bottom of the diagram). According to the COM-B framework, each decision in this journey is influenced by capability, motivation, and opportunity barriers. Capability and motivation barriers can be influenced by communications (blue). The theory of change also maps out the risks of the campaign (green), and which factors are outside of the campaign’s control (orange).

Campaign generated inequalities

What are campaign generated inequalities?

Campaign-generated inequalities occur when a campaign disproportionately benefits those who are already advantaged in society. A campaign may be successful at achieving the desired behaviour change across the population as a whole, while still increasing inequality due to having different impacts on different groups.

For example, a campaign to reduce smoking may have overall success, with a 20% reduction in the number of smokers across the population. However, a closer look at the data may reveal that the campaign had inequitable impacts. For example, a 40% reduction in smoking in the wealthiest areas but only a 5% reduction in smoking in the most disadvantaged areas. As a result, the campaign may not have had much of an impact on the audience that would benefit most from behaviour change. Inequalities like this can occur if part of the target audience are less able to access a campaign, understand it, and subsequently engage with it (see reference 14).

Campaign generated inequalities typically fall into three categories:

- Inequality in access occurs when the intervention is delivered through channels that are primarily used by only part of the audience. For example, if a campaign is delivered exclusively through digital channels such as Facebook and Spotify, those that lack reliable internet access or a smartphone will be unlikely to see your campaign.

- Inequality in uptake occurs when there are significant opportunity barriers to enacting the behaviour encouraged by the campaign, which may be unequally felt by different audiences. For example, if the behaviour takes significant time, those who are time-poor may not be able to enact the behaviour change required. Some inequality in uptake can be relieved if audiences are provided with sources of support and help. Barriers that produce this inequality are likely to be found around access to resources, cognitive load, and competing priorities. Campaigns that focus on individual behaviours without considering the role of someone’s environment or decision-making capacity are therefore unlikely to be effective in more disadvantaged populations.

What should I do about campaign generated Inequalities?

There are always going to be groups that are harder to reach and find behaviour change more challenging, no matter how good a campaign is. To expect a campaign to tailor to complete success for all audience segments is a huge challenge, and although something to aim for, may be unrealistic in a lot of circumstances. However, as communicators with access to research and behavioural tools set out in this guide, we are able to spend time working out what the potential inequalities our campaign may generate, and then minimising such inequalities as much as possible within your campaign budget and a robust assessment of what you can achieve.

To improve equality in access:

- Use a combination of digital and non-digital channels.

- Partner with community leaders and other free public-facing services such as libraries or places of worship.

- Use language that is accessible for those with lower levels of literacy or English language skills.

- In creative assets, use images of people that reflect the diversity of the campaign’s audience.

To improve equality in uptake:

- Ensure any research conducted to either diagnose a problem or evaluate your campaign contains a diverse representation of your target population.

- Consider how barriers to behaviour change vary across different audience segments, particularly for the most disadvantaged, and take this into account when designing the campaign and user journey.

- Provide an effective offline user journey as an alternative for those who lack digital access.

- Provide materials to help people navigate the required behaviour change, such as a physical pack or online chat box.

Implementation

Message design

This section sets out some strategies to design effective campaign messages and top lines.

These strategies are intended for campaigns that aim to change behaviour and drive action, rather than campaigns that intend to raise awareness or change opinion. However, some of the strategies may be applicable across all types of campaigns.

Principles of message design

In order to effectively spur action, a message must:

- Get the target audience’s attention

- Tell the target audience what they have to do

- Motivate the target audience to act

Or to phrase it differently, the message must remove capability barriers (awareness of the message, and knowledge about the action required) and motivation barriers (why the audience should act).

Get the target audience’s attention

In order to be successful, the message must get the attention of the target audience. They must understand that the message is meant for them, and they must not feel able to easily ignore the message.

Messaging should mirror the words and language used by the target audience to make sure they can recognise themselves in the message. For example, in a message about trading goods internationally, messaging could address the audience as “Anyone who buys or sells goods from abroad”, rather than “Traders,” which some people may not use to describe themselves.

Prompting questions to consider include:

- Will the audience recognise themselves in the message?

- What else might be competing for their attention?

- Does the message use their familiar language and words?

- How likely are they to trust the source of the message?

- Is the message easy for them to ignore?

For campaigns that try to encourage audiences to stop or reduce harmful behaviours, it might be more difficult to capture the audience’s attention. All people tend to disregard messages that warn about dangers, particularly where they already know that a behaviour is harmful but do not wish to stop (see section on Protection Motivation Theory).

Tell the target audience what they have to do

When encouraging an audience to take action, the message should be as specific as possible about exactly what they must do. The audience should be able to picture themselves carrying out the action, and the message should give them the information they need to make a plan.

For example, a message stating “Eat more vegetables” is clear, but the action is not very specific and it may be difficult for the audience to translate the instruction into a plan. “Add an extra serving of vegetables to every meal” is more specific, and helps the audience to form a concrete and achievable plan.

Prompting questions to consider include:

- Is the required behaviour clearly set out?

- Is the message in plain English?

- Does the message help people form a plan of action?

- Are the next steps clearly signposted?

- Does the message convey appropriate urgency and timelines?

- Is it clear in the message who is responsible for carrying out the behaviour?

Motivate the target audience to act

Finally, the message must motivate the target audience to act. The phrases chosen should be informed by analysis of the motivation barriers to action faced by the audience.

Audiences can be motivated by positive messages (“Keep the park nice for everyone”) or negative messages (“Don’t turn the park into a rubbish dump”). Insight about your audience should reveal which kind of messages will resonate the most. When a campaign involves a series of communications, communicators may wish to start with more positive messages, shifting to a more negative tone later to drive up urgency for those who have not yet taken action.

Prompting questions to consider include:

- Why would anyone want to follow the instructions?

- Are the consequences of not doing anything clearly set out?

- Does the message make people feel empowered to act?

- Does the action sound fun, interesting, or intriguing?

Communicating about threats and risks

Protection Motivation Theory describes how people typically behave in response to a threat or a risk.

This theory shows that individuals typically go through a two-stage decision making process in response to a threat: firstly, they appraise the risk, and secondly, they appraise how able they are to avert the risk through their behaviour.

According to this theory, if people don’t feel that they are able to avert the risk through their behaviour, they will attempt to cope with their fear by engaging in undesirable behaviours, such as denial, disengagement, or panic.

If people do feel that they are able to avert the risk through their behaviour, they will attempt to cope with the danger by engaging in suitable protective behaviours.

So, when planning a campaign to encourage people to enact protective behaviours in response to risk, campaign messaging should both:

- Help the audience understand how much risk they face

- Give the audience the confidence that they can reduce this risk through protective action, with clear instructions about what they should do.

Habits

What is a habit?

Habit is an automatic behaviour or pattern of behaviour established through repetition of an experience and imprinted in neural pathways so that it doesn’t require conscious planning.

Habits are often prompted by specific triggers, which are cues providing reminders of the previous action or routine, and helping us to perform it again. Triggers might be objects, actions, people, sounds, smells, or other elements of the external environment.

Build habits

There are a few principles communicators can draw on when a behaviour needs to be repeated for a successful behaviour change to take place:

- Help audiences create their own environmental cues to encourage habit formation. For example, if a campaign is trying to encourage people to take reusable bags to the supermarket, communications could suggest keeping reusable bags by the front door as a physical reminder to take them along. If a campaign is promoting the benefits of regularly switching energy suppliers, communications could encourage audiences to enter a calendar appointment each year to regularly review their current tariff and explore alternatives.

- Make use of natural opportunities to change routines and habitual behaviours. Significant life changes (such as moving house or becoming a parent) offer an ideal opportunity to establish new habits, due to the disruption of existing routines and the development of new ones. For example, if a campaign is encouraging individuals to stop smoking, targeting this towards people who are undergoing other life changes (such as starting a new job, or retiring) may increase the effectiveness of the campaign by allowing people to adopt new habits in line with new daily structures.

- Encouraging new behaviour as an addition to an existing behaviour or routine is likely to boost new habit adoption. For example, some breast cancer charities routinely provide shower stickers that show how to perform a breast check. Instead of asking people to take time out of their day to specifically perform this breast check, this campaign instead encouraged audiences to perform the check while showering, an existing daily routine that can be adjusted to incorporate this new habit.

Evaluation

Evaluation is about measuring whether the campaign has achieved its objectives. To evaluate effectively, the vision needs to be translated into a set of measurable campaign objectives with corresponding measures before the campaign is launched. If the evaluation method is not planned in advance, there is a risk that data to determine campaign effectiveness may not be available, or may be difficult to access.

To be able to identify whether and why the campaign was or was not effective, two things will be measured: the behaviour to influence (for example the proportion of girls choosing STEM subjects at A-level, or reporting rates of modern slavery) and the barriers to that behaviour (identified in the COM-B analysis).

This is because the campaign may only be designed to overcome one or two barriers, so its success at influencing the behaviour in question will partly depend on the strength of the other barriers at the time the campaign is running.

For example, a campaign designed to overcome the motivational barriers to frontline staff reporting modern slavery might have been very effective at overcoming motivational barriers, with staff highly engaged and motivated to make reports. However, if opportunity barriers (barriers outside the control of the audience) were present during the campaign, reporting rates might have remained stubbornly low – for example, if the telephone line to report such concerns had been unavailable. To avoid drawing incorrect conclusions about the campaign’s success, the behavioural outcome in question as well as the relevant barriers would ideally be monitored.

Another way of understanding this is to think back to the theory of change, which charts out all of the conditions that would need to be met in order for a particular behavioural outcome to take place. If any one of these conditions were not met, for example, because the campaign was unable or not designed to influence it, then the behaviour would not change. Measuring whether and to what extent these conditions are satisfied is therefore important where possible. This section provides guidance on how to do this.

Measuring the behaviour your campaign intends to influence

To illustrate, we will use the case study 2 of Modern Slavery provided earlier which had three campaign objectives:

- Reduce the number of people who are forced into modern slavery in the UK by informing them and the community of modern slavery risks and signposting them to the Modern Slavery Helpline.

- Increase reporting of suspected modern slavery among frontline staff.

- Increase understanding of the issue of modern slavery among the UK public.

For each of these objectives, communicators should decide how they can be measured. Below we set out examples of what could be measured against these objectives.

Objective 1: Reduce the number of people who are forced into modern slavery in the UK by informing them and the community of modern slavery risks and signposting them to the Modern Slavery Helpline.

What can be measured and how?

- Number of modern slavery offences recorded by police (ONS)

- Number of potential victims referred through UK National Referral Mechanism (ONS)

- Number of suspects of modern slavery flagged to Crown Prosecution Service for a charging decision (ONS)

- Number of prosecutions and convictions for modern slavery by Crown Prosecution Service (ONS)

- Calls to Modern Slavery Helpline (ONS)

- Awareness of modern slavery risks amongst UK public (polling, focus groups)

- Awareness of Modern Slavery Helpline amongst UK public (polling, qualitative research)

Objective 2: Increase reporting of suspected modern slavery among frontline staff

What can be measured and how?

- Calls to Modern Slavery Helpline (ONS)

- Self-reported usage of Modern Slavery Helpline by frontline staff (polling)

Objective 3: Increase understanding of the issue of modern slavery among the UK public

What can be measured and how?

- Proportion of UK public who are able to correctly identify what modern slavery is and how to report it (polling)

- Understanding of modern slavery by UK public (qualitative research)

Measuring the barriers to behaviour change

Monitoring whether the campaign did indeed overcome the barrier it intended to overcome will help understand whether the campaign changed behaviour via the intended route.

For example, the COM-B analysis of the barriers to reporting of modern slavery by frontline staff identified that whilst most professionals were aware of the signs, they did not feel empowered enough to act on their suspicions by phoning the helpline. The campaign was designed to overcome this barrier by making staff feel more comfortable to make reports.

Assuming that reporting rates increased throughout the campaign, how is it possible to know this was due to the campaign and not just due to an increase in the incidence in modern slavery?

One way of finding out is to see whether the campaign addressed the selected barrier, in this case, improving staff confidence in reporting. If evaluation shows that this barrier has been removed or reduced, then the campaign has been successful at tackling this barrier.

The tables below set out some of the key barriers to behaviour change for this case study, and methods that could be used to measure them.

Motivation and capability barriers that impact confidence

| Barrier | What can be measured and how? |

|---|---|

| Modern slavery is not something that the audience typically thinks about | Unprompted recall of need to look out for signs of modern slavery (focus groups) Unprompted discussion of modern slavery (focus groups) |

| The audience are unaware of the correct way to report | Ability to correctly identify reporting mechanism (staff survey) |

| The audience are afraid of getting it wrong and feel like they need comprehensive evidence | Expressions of confidence by staff in knowing that they can report without fear of getting it wrong (focus groups, staff survey) |

| The audience are afraid of being accused of stereotyping or making assumptions | Fewer expressions of this view (focus groups) |

| The audience don’t feel that it’s appropriate to intervene in others’ affairs | Fewer expressions of this view (focus groups) |

Opportunity barriers that could prevent behaviour change regardless of how effective the campaign is

| Barrier | What can be measured and how? |

|---|---|

| The audience has time-pressured jobs that makes reporting difficult during working hours | Staff perceptions of workload and time available to consider and report modern slavery (focus groups) Organisational changes that could impact time pressure of roles, e.g., staff cuts, restructures |

| Some professionals are not allowed to use their phones whilst on duty | Local Authorities’ (LAs) rules regarding staff use of phones (desk research, contacting LAs) Staff self-reports of ability to use phones (focus groups, staff surveys) |

While every effort should be taken to identify and remove opportunity barriers prior to the start of a campaign, by evaluating the campaign’s impact on individual barriers we can obtain a more granular understanding of how exactly the campaign performed and which barriers remained in place.

About the GCS behavioural science team

This guide was developed by the GCS Behavioural Science Team based in the Cabinet Office. The team provides expert support to central government campaigns, and additionally offers behavioural science consultancy services across government, covering communications, policy and operations.

Our approach involves breaking problems down into their constituent parts to understand the desired behaviours and how barriers to their completion manifest themselves to different groups of people. Most behaviours can be explained by individuals responding to their situation and environment in a way that makes sense to them. We believe that most people endeavour to do the best they can, given their circumstances. Detailed exploration often reveals that behaviour that may look “irrational” is often a perfectly logical response to complexity, stress, ambiguity, or uncertainty.

We see our role as designing communications that help people make decisions and take actions. To achieve this we go further than merely applying solutions from the behavioural science literature – we instead analyse the problem using behavioural science frameworks, and develop bespoke, contextual solutions. The team then develops recommendations designed to systematically overcome those barriers in psychologically relevant ways.

Contact the behavioural science team: behavioural-science@cabinetoffice.gov.uk

Acknowledgements

This guide was written by (in alphabetical order): Dr Laura de Molière, Abigail Emery, Dr Paulina Lang, Dr Moira Nicolson, and Eleanor Prince.

It draws on the work of Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West of University College London.

The authors thank colleagues across government for providing their comments and suggestions.

References

- Microsoft Corporation (2017) Why Europe’s Girls Aren’t Studying STEM

- Cambridge Assessment AS and A Level Choice Factsheet 2 – Gender makes a difference

- Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M. & West, R. (2011) The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42.

- Tai et al (2006) Career choice. Planning early for careers in science. Science

- Cheryan, S., Siy, J.O., Vichayapai, M., Drury, B.J., & Kim, S. (2011) Do female and male role models who embody STEM stereotypes hinder women’s anticipated success in STEM? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(6), 656-664.

- Stout, J.G., Dasgupta, N., Hunsinger, M., McManus, M.A. (2011) STEMing the tide: using ingroup experts to inoculate women’s self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), pp. 255-270.

- Jacobs. J., & Eccles, J.S. (1992) The impact of mothers’ gender-role stereotypic beliefs on mothers’ and children’s ability perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), pp. 932-944.

- Tiedemann, J. (2000) Gender-related beliefs of teachers in elementary school mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 41(2), pp.191-207.

- Qualified for the Future: Quantifying demand for arts humanities social science skills

- Stibe, A., & Cugelman, B. (2016) Persuasive backfiring: When behavior change interventions trigger unintended negative outcomes. International conference on persuasive technology, pp. 65-77. Springer, Cham.

- Doleac, J. L., & Hansen, B. (2020) The unintended consequences of “ban the box”: Statistical discrimination and employment outcomes when criminal histories are hidden.’ Journal of Labor Economics, 38(2), 321-374.

- Guiso, L., Monte, F., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2008) Culture, gender, and math. Science, 320(5880), 1164.

- Breda, T., & Napp, C. (2019) Girls’ comparative advantage in reading can largely explain the gender gap in math-related fields. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(31), pp. 15435-15440.

- Veinot, T.C., Mitchell, H., & Ancker, J.S. (2018) Good intentions are not enough: how informatics interventions can worsen inequality, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(8), pp. 1080–1088.