The Wall of Beliefs

A toolkit for understanding false beliefs and developing effective counter-disinformation strategies

This guide is aimed at policymakers and communicators whose work may be impacted by false narratives and misinformation.

The guide is generally applicable across all areas of misinformation from health to climate change to myths around violence against women and girls. It can help guide you to respond to incorrect press or social media coverage and general public misconceptions.

In some cases, practitioners will be dealing with more coordinated and dangerous state-sponsored threats. In these cases, our guide should be seen as a supplement to, not a replacement of, the advice available from expert counter-disinformation practitioners.

On this page:

- Video

- Foreword

- The role of governments in countering false beliefs

- Summary

- Introduction

- Section 1: The “Wall of Beliefs” – A new model for understanding beliefs

- Section 2: Strategy matrix – Four approaches to countering disinformation and false beliefs

- Section 3: Using the Wall of Beliefs to develop communications plans

- The boundaries of the Wall of Beliefs

- References

Video

Watch the 2 minutes video “Wall of belief: understanding false beliefs and developing effective counter-disinformation strategies”.

The Government Communication Service Behavioural Science team presents the Wall of Beliefs.

On screen there is a cartoon image of a man with a woolly hat and glasses, transitioning into a zoomed in image of the inside of his head.

You’re asked to imagine that our beliefs are like the bricks that make up a wall. A wall appears composed of lots of individual bricks, some of which are annotated. The notes read: I could run a marathon, the earth is round, I’m very decisive, vaccines contain dangerous ingredients, my family never lie, bad things sometimes happen for no reason, I am good at most sports, my parents are always right. Altogether these bricks make a sturdy wall.

The brick wall fades away and you are shown three bricks one by one. The first brick has basket balls bouncing on top of it and it reads I am good at most sports. This is an example of a belief that we might have about ourselves. The second brick appears and reads My FamiIy Never Lie, and shows three cartoon heads, one of an older woman and older man and another of a young girl, denoting a family with a mum, father and daughter. This is an example of a belief we have about others.

The final brick reads Bad things sometimes happen for no reason and this is accompanied by a cartoon man with a hat holding an icecream cone which is set on fire by a lightning bolt that flashes out from a dark storm cloud. This is an example of a belief we might have about the world around us.

Some bricks will be given by friends, family or other trusted sources. On screen there is a cartoon head of a young boy with a hat, representing a friend, the two parents from earlier, representing family, and a new face, a woman with gray curly hair and glasses representing another trusted source. Her face is accompanied by a new brick saying vaccines contain dangerous ingredients.

Bricks like these from trusted sources might be very important to people. A vaccine syringe appears on screen injecting that brick, along with a yellow skull and crossbones warning sign.

The woman disappears and on screen is a single column of bricks. We are told that trying to remove a single brick may be impossible. Or it may cause a collapse. This is represented by the column of bricks being knocked down by wrecking ball and a crane. Two bricks get carried off the screen by a bulldozer. These bricks read My family never lie and vaccines contain dangerous ingredients.

That’s why you might have to remove and replace several bricks to fit a new brick in. On screen is a brick wall made up of lots of bricks, with a gap at the centre Two bricks rise up out of the wall. They read bad things sometimes happen for no reason and vaccines contain dangerous ingredients. A new brick slides into the wall that reads vaccines have been thoroughly tested. However now the other two bricks can no longer slide back into place as they don’t fit.

Other bricks might be very stuck in place. The animation shows another brick that reads I have a strong immune system. It is rattling around in its spot but can’t escape because it is surrounded by so many other bricks.

Other bricks are looser and easier to remove. A brick that reads I could run a marathon is right at the edge of the wall and moves off screen, leaving the rest of the wall intact.

However, rearranging and rebuilding is tiring and takes effort that people don’t always have. To remind us of this, the solid wall appears again with a crane and a bulldozer on either side.

When trying to adjust a brick, consider the surrounding and supporting bricks. The animation zooms in on a brick in the middle of the wall, the brick from earlier in the animation that reads vaccines contain dangerous ingredients. You are asked: what bricks does it depend on, what other bricks depend on it? One by one you are shown what bricks it depends on. There are two foundational bricks that read I don’t trust the government and chemicals can be harmful for you. Adjacent to the brick is one that reads I’m afraid of becoming unwell and I know someone who got ill after being vaccinated. You are also shown a brick that depends on it. A brick that reads Covid is a hoax.

We are told that if you’re trying to replace or remove a brick, then we should help people rebuild the right part of their wall easily. On screen appears the cartoon face of two doctors, one of whom is a young woman wearing a stethoscope and headscarf with a speech bubble saying vaccines are safe and effective. The other face is an older man with gray hair saying the vaccines have been tested extensively. This leads to a transformation of two foundational bricks in the wall. The brick that reads vaccines contain dangerous chemicals is replaced with a new brick reading my doctor trusts vaccines. The brick that reads I don’t trust the government changes to a new brick that reads I trust my doctor.

You can also challenge harmful behaviours without removing any bricks. An image appears of a young girl tucked up in bed with a thermometer in her mouth because she is sick. A new brick appears on screen and lands on the top of the wall that reads staying at home when I’m ill is a good thing to do.

The Cabinet Office Behavioural Science team wants to help people build strong and stable walls that can be rebuilt easily when we learn new things. A collage of faces fill the screen and transform into blank rooms that denote the inside of their minds and which are then filled with brick walls, denoting the beliefs they hold.

The video ends with a call to action to search the .gov.uk website for wall of beliefs to find out more.

Foreword

Words and stories are increasingly exploited by hostile actors seeking to sow mistrust, and the rise of disinformation and misinformation poses a growing threat to our democracy and the trust between citizens and governments across the world.

Government communications is often the front line in this volatile information war, and it is essential that government communicators have a deep understanding of disinformation and false beliefs – why they are adopted, how they spread, and why they can be so difficult to challenge.

Historically, counter-disinformation approaches have focused on debunking falsehoods and busting myths, based on the assumption that false beliefs arise because people simply don’t have access to correct information. The Wall of Beliefs is a toolkit to help communicators take a broader perspective, understanding the role of identity, relationships, and worldview in the development of beliefs and susceptibility to false stories.

With this understanding, we can unearth new insights about our audiences, and develop more sophisticated strategies to respond to false information.

The Government Communications Service (GCS) is working with countries across the world to expose the threat of disinformation and take effective action to counter it. We must not surrender to those who spread falsehoods, and the Wall of Beliefs toolkit will play a vital role in helping communicators worldwide understand the psychology of false beliefs, and use this knowledge to communicate the truth effectively.

Simon Baugh, Chief Executive of Government Communication Service

The role of governments in countering false beliefs

In a democracy, it is essential that the public can access full and accurate information to make free and informed decisions, and governments have a duty to facilitate this access. When information landscapes are crowded with false information, it becomes increasingly difficult for the public to discern truth from falsehood, and to make important decisions with accurate information to hand.

While it is not the role of governments to restrict free expression or dictate which beliefs are acceptable, it is the role of governments to give the public an environment in which they can make informed choices based on truthful information without interference. The public have a right to freedom from false information, freedom from interference by hostile actors, and freedom from dangerous advice that may cause them harm.

In some cases, mis- and disinformation can cause people to adopt false beliefs that lead to harmful behaviours. By fostering a healthy information landscape and taking the steps outlined in this pack, governments can fulfil their duty to protect people from harm caused by false beliefs and misleading narratives.

To take action effectively, governments should design strategies that are based on high-quality insight about why people hold and sustain certain beliefs. The actions that government takes to counter mis- and disinformation using the strategies outlined in this pack should at all times be guided by the values of Integrity, Honesty, Objectivity and Impartiality and the standards of behaviour outlined in the Civil Service Code as well as in line with the law. If any Civil Servant becomes aware of actions that conflict with the Civil Service Code they should follow the reporting procedure outlined in the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010.

Summary

- Overturning false beliefs is not as straightforward as simply supplying true information, or debunking falsehoods. This teaching pack sets out the many influences on our beliefs, and why they can be resistant to change.

- When tackling disinformation and false beliefs, it is essential to understand the relevant audience, their worldview, and the wider influences on their beliefs and behaviours. The information in this pack offers credible routes to overcoming false beliefs based on audience insight.

- There are at least four overarching strategies that can be used to manage false beliefs, using a range of communication and policy tools. This pack explains how to choose an appropriate strategy depending on the characteristics of the belief in question.

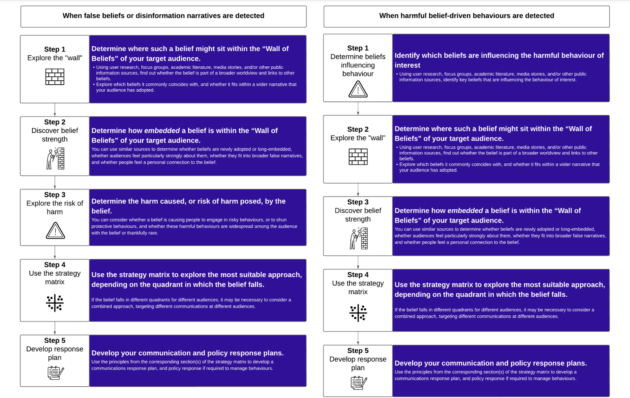

- There is a simple insight-gathering process that communicators and policy makers can follow when they identify false beliefs circulating, or when they recognise harmful belief-driven behaviours. This pack sets out this five-step process, to give structure to efforts to manage false beliefs and harmful behaviours.

Introduction

Disinformation, and how to counter it, is an increasingly important phenomenon for communicators to understand.

In a crowded and often confusing information landscape, it is more important than ever that democratic governments, media organisations, and civil society groups work together to counter the increasing threat posed by disinformation, spread to sow mistrust, and to divide and damage societies.

Governments have a responsibility to the public to provide them with reliable information, to promote the truth, and to help people navigate their way through the increasingly complex information environment.

There are several pieces to this puzzle.

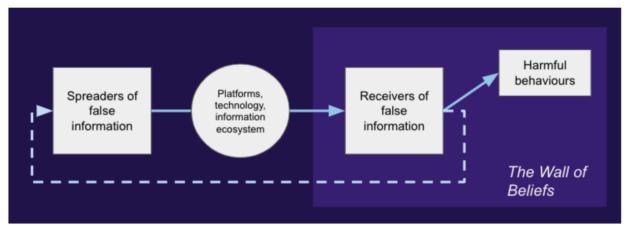

It is important to understand the behaviours and motives of hostile actors who seek to spread falsehoods, and to take steps to neutralise them to prevent false stories from entering the information ecosystem in the first place.

It is also necessary to consider how technology and platforms contribute to the spread of disinformation, working together to implement interventions and adjustments that reduce the reach and influence of false stories.

For communicators, however, a key challenge is how to respond once falsehoods have entered public discourse and have become adopted as beliefs among members of the public. This part of the puzzle is the focus of the Wall of Beliefs – how to use communications to disrupt and dismantle false narratives that lead to polarisation, conflict, and harmful behaviours.

Directly confronting myths and misconceptions can intuitively seem like the right thing to do. Many common counter-disinformation strategies – such as mythbusting and rebuttals – are based on this intuition. But these strategies are only appropriate in certain circumstances: they often fail to make a significant impact, and sometimes backfire.

To better combat disinformation, communicators and other government professionals need a strong understanding of how beliefs, false or true, are adopted, sustained, and given up.

The first part of this pack explains beliefs using a simple model, the “Wall of Beliefs”, which illustrates how beliefs take hold and why they are not always easy to change.

The second part of this pack introduces a Strategy Matrix that is designed to help communicators choose the most appropriate strategy to counter a specific false belief among an audience. It builds on the basic “Wall of Beliefs” model, turning the resulting insights into actionable strategy advice.

Section 1: The “Wall of Beliefs” – A new model for understanding beliefs

Our intuition can lead us astray: why mythbusting and rebuttals often fail

Mythbusting, debunking and rebuttal approaches are based on the assumption that lack of true information is the primary cause of false beliefs. From this intuitive assumption stems an intuitive solution: supplying correct information should be enough to overturn misconceptions. In academic literature, this is known as an “information-deficit model” of belief.

The “Wall of Beliefs” shows us that beliefs aren’t that straightforward, and that lack of information is not a sufficient explanation for why false beliefs take hold.

Apart from having varied effectiveness, fact-supplying approaches can sometimes backfire.

Publicly challenging false information can unwittingly amplify it, bringing it to a wider audience. This can make the information more memorable and familiar, increasing its presumed credibility, especially if addressed directly on official channels. Directly confronting myths can also imply that there are two legitimate sides to a debate, increasing the perception that there is a genuine controversy.

And when people feel that their deeply-held beliefs are being directly challenged, they may experience psychological reactance – an emotional state that makes them feel more determined to hold to their beliefs, viewing the challenger as an adversary.

The “Wall of Beliefs”

The “Wall of Beliefs” aims to give communicators an introduction to the psychology of disinformation. The model strives to be simple, memorable, and intuitive rather than granular and academic. It uses the metaphor of a brick wall to emphasise the interdependency of beliefs.

The tool is not intended to impart a sophisticated understanding of the cognitive mechanisms behind belief formation. Rather, the model provides an accessible introduction to belief systems, moving communicators beyond an intuitive (but simplistic) information-deficit model of belief.

Table 1: The “Wall of Beliefs” script

| Metaphor | Literal meaning |

|---|---|

| Beliefs are like the bricks that make up a wall. All together, these bricks make a sturdy wall. | Our beliefs are linked and interdependent. Each individual brick rests on others. A person’s worldview and beliefs therefore often remain stable over time. |

| Some bricks will be given by friends, family, or other trusted sources. These bricks might be very important to people. | Beliefs that are strongly linked to personal relationships and identity may be particularly embedded and resistant to change. |

| Trying to remove a single brick may be impossible, or it may cause a collapse. | Trying to correct a single false belief might be difficult if it’s integral to an individual’s mental model or gives rise to many other beliefs. Tackling these deeply embedded beliefs can have unpredictable consequences for someone’s worldview. |

| You might have to remove and replace several bricks to fit a new brick in. | Correcting beliefs that are part of a mental model, or which give rise to multiple other beliefs, might require quite significant changes in understanding and new mental models to be built, with new information. |

| Some bricks might be very stuck in place, while others are looser and easy to remove. | New or uncertain beliefs might be easy to change, while others might be harder to change. |

| Rebuilding a wall is tiring, and takes effort that people don’t always have. | Changing your beliefs takes effort and consideration, and people may not wish to disturb a stable belief system. |

| When trying to adjust a brick, consider the surrounding and supporting bricks. What bricks does it depend on? What other bricks depend on it? | When trying to change a person’s beliefs, you need to consider linked beliefs, and how beliefs fit into existing mental models. |

| If you are trying to replace or remove a brick, help people rebuild the right part of their wall easily. | When disrupting existing mental models, help people rebuild their understanding with clear, accessible, and satisfying explanations. |

| You can also challenge harmful behaviours without moving any bricks. | In some cases, challenging harmful behaviours without immediately tackling beliefs and attitudes might be the best course of action. |

Why is supplying true information not enough to change beliefs?

There are many reasons why people may adopt and sustain beliefs despite challenges, or why they may continue to believe or share false information despite corrections and counter-disinformation communications.

Beliefs are intensely personal, and can fulfil many needs for people beyond simply aiming to discover the truth:

- Community and belonging: People may hold the same beliefs as others in their community or social group, to secure a sense of belonging and a shared understanding.

- Relationships with others: People may hold beliefs that come from trusted friends or family members, to nurture those relationships, or avoid conflict.

- Explanations for complexity: People may hold beliefs that purport to provide a simple explanation for complicated events, in an attempt to avoid feelings of helplessness or anxiety.

- Self-esteem: People may hold beliefs that preserve their own self-esteem or that of a group they are in (for example, believing in conspiracies that pin the blame for negative events on a certain individual, group, or institution)

- Justify behaviours: People may hold beliefs that excuse or justify behaviours that they wish to engage in or avoid (for example, adopting climate-sceptic beliefs out of reactance to being instructed to adopt green behaviour changes they do not want or cannot afford to adopt).

- Save face: People may maintain beliefs that they have publicly proclaimed a strong and sincere commitment to at some point in the past, to avoid the embarrassment or perceived social indignity associated with changing their mind (“saving face”).

- Preserve sacred values: People may hold onto beliefs because they form a foundational part of their identity and worldview, the maintenance of which is essential for their self-esteem and ability to interpret and understand the world (for example, many communities will hold shared ideals, known as “sacred values”, such as justice, the sanctity of human life or belief in a higher power which will be non-negotiable).

- Fear of reprisal: People may hold onto beliefs because they fear reprisals for adopting alternative ones (for example, citizens living in oppressed nations can be sent to prison or even killed for expressing views that are in opposition to state-sanctioned narratives).

In some cases, people may actively avoid information that challenges their beliefs, or may steadfastly ignore their own doubts or concerns in order to sustain beliefs that serve them in some way. In these circumstances, simply providing true information is unlikely to successfully overturn false beliefs.

Section 2: Strategy matrix – Four approaches to countering disinformation and false beliefs

With a better model of belief formation in hand, we can now turn to the best ways to combat the false beliefs that mis- and disinformation might cause.

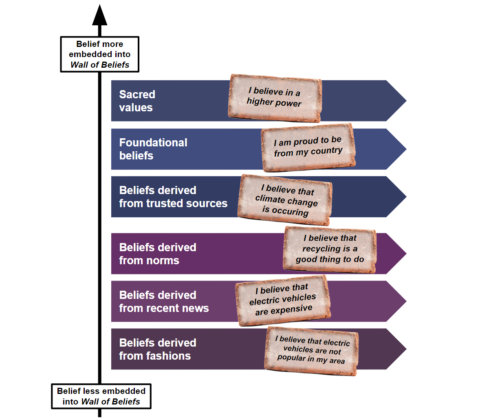

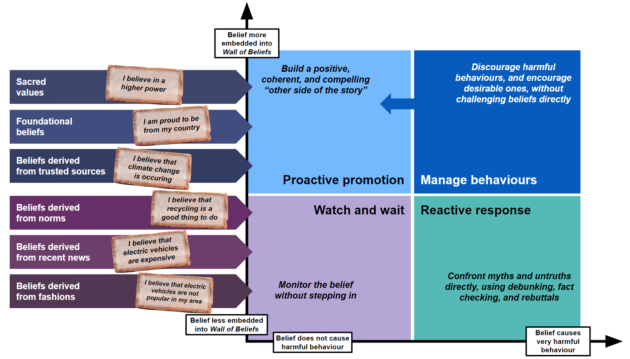

Some false beliefs are easy to change – particularly those that might be new or uncertain – while other false beliefs may be more embedded as they form part of someone’s identity or worldview. As illustrated in the diagram below, the most deeply embedded beliefs are likely to be foundational beliefs that stem from sacred values. The least embedded beliefs might be those derived from recent news or rumours.

Beliefs can cause harmful behaviours (or discourage desirable behaviours) by leading people to believe those safe behaviours are actually harmful (for example, that the MMR, Measles, Mumps and Rubella, vaccine causes autism) or that harmful behaviours are actually safe (for example, that unproven cures are effective against Coronavirus [COVID-19]). While some false beliefs lead to harmful behaviours, other false beliefs might not cause any behaviour change at all, at least in the short term.

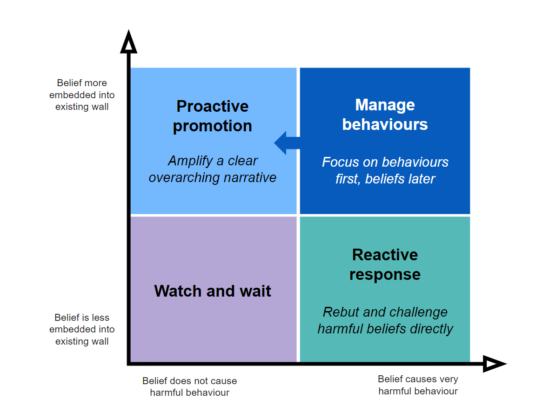

The best choice of strategy to counter false beliefs depends on both these factors – how embedded the belief is in the “Wall of Beliefs”, and the extent to which it directly causes harmful behaviours.

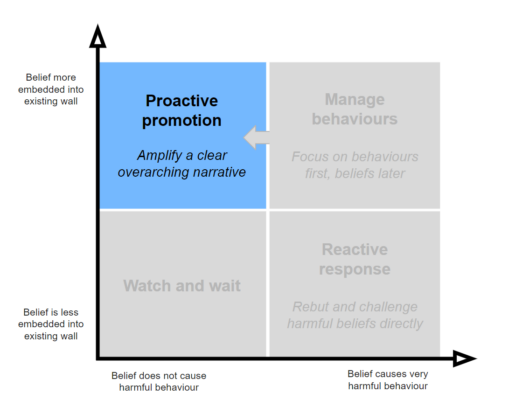

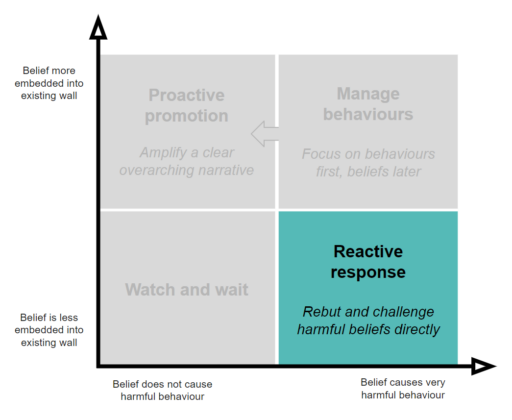

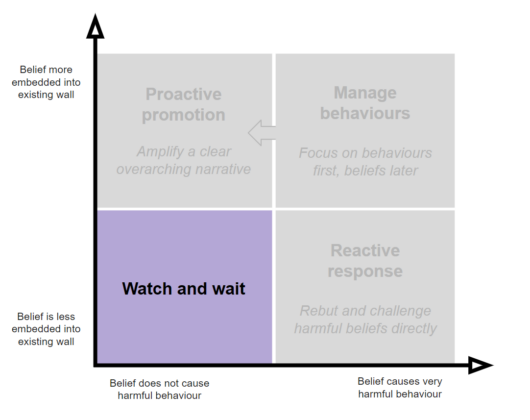

The second diagram sets out four broad strategic approaches, and the conditions under which they should be deployed:

- Manage behaviours

- Proactive promotion

- Reactive response

- Watch and wait

It is worth noting that for some false beliefs, different audiences will fall into different quadrants (for example, a belief may be held strongly in some groups, but not others), and thus it may be necessary to use multiple strategies at once, targeted towards different audiences.

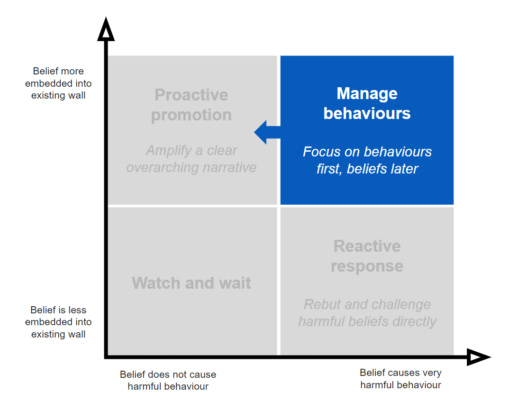

Manage behaviours

When beliefs are highly embedded and also cause harmful behaviours in the short term, the best strategy may be to challenge these harmful behaviours directly without initially challenging the false beliefs that led to them.

Once harmful behaviours are managed, communicators can shift to a proactive promotion strategy to tackle deeply-embedded beliefs as indicated by the arrow in the diagram above (proactive promotion is covered in the next section).

What is managing behaviours?

Beliefs influence behaviours, but they are not the only influence. Sometimes people do things that are inconsistent with their beliefs. Communications (and other interventions) can be used effectively to encourage behaviour change without tackling the underlying beliefs that lead to the harmful behaviour.

Methods of challenging behaviours without challenging beliefs include:

- Making a desired behaviour as easy as possible

- Making a harmful behaviour more difficult

- Using a different messenger to deliver instructions and advice

- Communicating the desired behaviour using arguments that are unrelated to contentious beliefs or specific worldviews.

Why is managing behaviours recommended in this situation?

When highly embedded beliefs are causing harmful behaviours, there may not be enough time to use communications to influence a change in these beliefs. Therefore, it may be most appropriate in the short-term to prioritise behaviour change and mitigation of the most harmful behaviours.

Over time, behaviour change can eventually lead to changes in belief. Self-perception theory suggests that our actions influence our self-image, which can in turn influence our behaviour. By promoting behaviour change we can thus eventually create changes in beliefs and norms.

While challenging behaviours should be a priority where there is risk of immediate harm, this strategy can be implemented alongside a long-term proactive promotion strategy to address deeply-held beliefs over a longer time period.

How to design an effective strategy to manage behaviours

Incentives and barriers

Work with policymakers to put incentives and barriers in place to make harmful behaviours more difficult, and desired behaviours easier.

Introduce barriers to people carrying out harmful behaviours

Some particularly harmful behaviours can be reduced by making them harder to undertake, such as by introducing bans, fines, regulations or practical hurdles. While communications alone can’t introduce these barriers, communications can publicise the existence of barriers.

For example, in 2012, the UK Government banned the sale of incandescent light bulbs so that only energy-efficient bulbs were sold in UK shops, meaning that when people need to replace their incandescent bulbs they can only buy new energy-efficient versions, irrespective of their beliefs about climate change.

Remove practical hurdles to people carrying out the desired behaviour

If people’s beliefs are preventing them from doing a desirable behaviour (for example, getting vaccinated), identify whether there are any practical factors that are also hindering people’s ability to carry out the behaviour, and work with policymakers to remove them. If a behaviour is complex, time-consuming or costly, policymakers should find ways to make it quicker, simpler and cheaper, and communications can be used to inform people about changes that make the desired behaviour easier.

For example, a key feature of the vaccine rollout in the UK is that people have been able to get vaccinated in their local pharmacies and GP surgeries, as well as large vaccination sites without making appointments (walk-ins). This means that for people who were hesitant about getting vaccinated, money and time do not pose additional barriers, and because vaccinations are available on an ongoing basis people have had plenty of time to change their minds for e.g. as evidence continues to demonstrate their efficacy and safety.

Make desired behaviours attractive or rewarding

If people’s beliefs are preventing them from doing a desirable behaviour, making the desired behaviour attractive or rewarding may increase the likelihood that people will do it anyway.

For example, although air travel is the preferred mode of transport between countries, between 1994-2020, an estimated 20 million people chose to travel between the UK and France on the Eurostar. The Eurostar does not brand itself as green and people often react strongly against calls to reduce air travel for the sake of the environment; rather, the associated carbon savings of these journeys are a positive unintended consequence of the Eurostar’s reputation as a comfortable and convenient way to travel.

What to communicate

Showcase other people undertaking the desired behaviour

In some cases, people will take their cues about how to behave from what they see other people around them doing, especially people with whom they share a social identity. Showcase examples of people undertaking the desired behavioural action, but without linking their behaviour to a change in underlying belief. For example, a poster showing pregnant women getting vaccinated could serve as a social cue to other pregnant women to get vaccinated.

How to communicate

Be specific about what you want people to do

When promoting a behaviour, people are much more likely to do it if you clearly spell out what you want them to do (the call to action) and how. The action should also feel achievable. For example, a standard message issued by the UK Government at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic – “Wash your hands more frequently and for at least 20 seconds” – on a graphic of someone with soapy hands is extremely clear, very specific and feels achievable.

Make calls to action easy to understand

Another important factor is making sure that calls to action are easy for your target audience to understand, taking into account the varying comprehension needs and challenges. In addition to making the call to action specific, messages aimed at a broad audience may also need to be translated into multiple languages and should be written free of jargon or technical terms.

Frame desirable actions as if they are the default behaviour

A good way to motivate people to adopt the behaviour promoted in communications is to signal that the desirable behaviour is the standard course of action. For example, when inviting people to book a vaccine appointment, messages like “It’s time to book your appointment” carry a stronger suggestion of a default action than messages like “It’s time to decide if you want to get vaccinated.”

Avoid linking desired behaviour to beliefs, values or worldviews

When promoting a behaviour, avoid linking it to specific beliefs, values or worldviews, to reduce the likelihood that people will experience psychological reactance or cognitive dissonance.

For example, do not promote vaccination by saying “Responsible citizens get vaccinated” as people with vaccine-hesitant beliefs may perceive this as an attack on their values and identity.

Avoid accusing people who change their beliefs of inconsistency or hypocrisy

Do not accuse people of being inconsistent or hypocritical if they undertake desirable behaviours that appear to be inconsistent with their values or worldviews, as this might be perceived as an attack, increasing psychological reactance or cognitive dissonance.

Broader considerations

Design policies and processes to enable people to change behaviour whilst saving face

Ensure policies and processes allow people to easily change their behaviour without requiring them to publicly acknowledge inconsistency with their underlying beliefs or to confront a recent change in their beliefs. By helping people to save face, behaviour change will be more likely.

Managing behaviours: Examples

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some groups strongly rejected wearing face masks, often accompanied by negative attitudes towards other rules and guidance to reduce the spread of the virus. These anti-mask views often coincided with belief that the risk of COVID-19 was being exaggerated by authorities and the health service, and doubt in the trustworthiness of government advice. These attitudes were deeply embedded among a small but significant audience segment and led to people refusing to follow guidance putting themselves and others at risk.

Challenging people’s deeply-held beliefs about the government and health service is a significant undertaking, and would not have been effective quickly enough to prevent immediate harmful behaviours.

So rather than targeting this group with adversarial debunking messages, a simpler technique was to make the target behaviours as easy as possible. Providing free masks at the entrance to hospitals, and making social distancing a “default” in public spaces (with signage and floor markings) reduced the need for sceptical individuals to make a conscious decision to follow the guidance against their own beliefs.

Voting behaviour

In many countries, voting is more common in some groups than others. Decisions about whether to vote have a range of influences, which include whether people feel like their vote will have a meaningful impact on the outcome and whether they feel a civic duty to vote. Deep distrust in politics and a belief that “nothing will change” are difficult attitudes to challenge in the short term.

A more effective strategy, then, might be to make voting as easy and straightforward as possible. If voting requires very little time and energy, people may be tempted to do it anyway, even if they do not have strong motivation to do so.

If unenthusiastic voters start to vote regularly, due to the ease of voting, then this may also eventually lead to a change in self-perception, with people perceiving themselves as more politically engaged than before. This may lead to other attitude and behaviour changes in the longer term.

Sharing false beliefs online

Some false beliefs (such as anti-vaccination sentiment) give people a sense of belonging within a particular community or social status for holding and expressing those views. People who hold these beliefs may be inclined to share these views regularly with other people in their community, especially on online platforms, where these views can reach large numbers quickly.

Rather than change the underlying beliefs, social media platforms have implemented several measures to make people less likely to share misinformation. Articles flagged as “disputed” are shown less prominently on Facebook, meaning that fewer people have the opportunity to see them and share them. These articles are also flagged with a “disputed” or “misleading” marker, making them less socially acceptable to spread. WhatsApp similarly flags virally shared content to help people discern between viral content and messages written by their immediate network.

Proactive promotion

For beliefs that are embedded, but don’t cause harmful behaviour in the short term, a proactive promotion (sometimes known as a counter-brand) approach is recommended.

What is proactive promotion?

Proactive promotion is a strategy that centres around communicating the truth – but without directly engaging with false stories or myths.

A proactive promotion strategy requires communicating true information in a compelling way, using a range of channels, with particular focus on presenting information in a way that is easy to understand and recall.

The goal of proactive promotion is not to directly counter myths, but to consistently communicate an accurate and coherent “other side of the story” that deepens public understanding of the truth and builds resilience to false information.

It requires storytelling and the development of a narrative. In other words, it is not enough to communicate facts and figures alone – they need to be contextualised in communication that explains why, how, and so what?

To execute a proactive promotion strategy, communicators must:

- Establish true information, and build it into a compelling and coherent story that gets across the key facts

- Use this narrative to design memorable and accessible communication and campaign materials (for example, articles, blogs, speeches, and social media posts) that repeat and reinforce this true information

- Share these materials consistently over time, using a range of channels, to build public understanding and knowledge about the issue at hand.

Why is proactive promotion recommended in this situation?

When beliefs are embedded and resistant to change, this is typically because they form part of a person’s “worldview” – a set of beliefs that link together and influence how the person interprets the world around them.

When people feel that their worldview is being challenged directly, they may feel defiant and even more determined to hold on to their beliefs, viewing the challenger as an adversary. Proactive promotion approaches aim to help people construct a new and more informed worldview over the longer term, rather than tackling individual false beliefs head-on.

Research shows that people are more inclined to believe information that is straightforward and easily comes to mind. But in many situations, myths and false stories are appealingly simple, while the truth is more complicated and nuanced. Proactive promotion approaches aim to make the truth as straightforward, memorable, and coherent as possible so that people don’t fall victim to false information while seeking clear answers about complicated topics.

Proactive promotion is typically a medium to long-term strategy and is, therefore, most appropriate when the false belief is not causing immediate harmful behaviours.

How to design an effective proactive promotion strategy

Plan and prepare

Determine whether beliefs are fulfilling a need for the audience

People may adopt false beliefs for many reasons, such as needing to feel a sense of belonging in a group, or needing a simple explanation for complex and disconnected events. Consider whether there are other ways to fulfil the audience’s needs, and use communication and campaign materials to advance these efforts where possible.

What to communicate

Develop a story that gets across the key facts, based on truthful information

Establish the facts of the situation, and develop them into a coherent and consistent narrative that “tells the story” of the truth. Use this information to develop interesting and engaging communications and campaigns that reinforce this truth.

Amplify new information and emerging evidence

People may find it easier to change their beliefs when presented with new information, as updating beliefs in response to new evidence is typically more desirable and less emotionally and socially costly than changing beliefs simply due to reconsidering existing evidence.

Highlight unknowns and uncertainties

Where there is uncertainty or a lack of evidence, acknowledge this directly, and explain why information is unknown or uncertain.

Demonstrate that changing your mind is possible

Use first-person accounts or case studies to show that others have adopted new beliefs or have changed their views in response to new information, to reduce perceived stigma or embarrassment associated with changing beliefs.

Encourage doubts, rather than directly attacking sincere beliefs

People with conspiratorial beliefs may experience doubts about some elements of their beliefs, and messaging should encourage them to think more deeply about these doubts, drawing attention to the lack of evidence or corroboration for more extreme or doubtful claims. For example, if someone believes that vaccines are part of a global conspiracy to harm people, drawing their attention to historical diseases that have been eradicated by vaccines may be more effective than ridiculing their conspiratorial beliefs.

Help people explore their doubts

Sometimes people experience doubts about their beliefs but are unwilling to consider changing them as it can feel uncomfortable or overwhelming. Help people explore their doubts without rushing them by signposting them to further information or specialist advice if they are struggling with their beliefs.

Align messaging with the audience’s sacred values

Identify any important sacred values held by the audience, and appeal to these in communication and campaign materials. For example, if the relevant audience is highly patriotic, campaign materials could set out facts in a way that encourages national pride.

Avoid positioning messaging in opposition to the audience’s sacred values

People are unlikely to be receptive to messages that challenge their sacred values. For example, if talking to a religious audience about vaccination, a message like “Your faith won’t protect you from disease” is likely to be rejected and perceived as an attack.

How to communicate

Utilise teachable moments

A teachable moment is a time when audiences are more receptive to new information, due to external events that make relevant topics salient or widely known. “Teachable moments” can provide a useful trigger point to amplify truthful information to counter disinformation narratives. For example, in early 2020 a record 47% of the UK’s power came from renewable energy, which provided a useful teachable moment to inform the public about significant Government efforts to increase the use of green energy sources.

Use a range of channels, including in-group messengers

Determine which messengers and channels are trusted by the relevant audience, and seek to share the narrative through these messengers and channels. Ideally, ensure that information is shared through multiple channels that are not perceived as closely aligned by audiences.

Broader considerations

Minimise confusion and noise in the information landscape

Ensure that information and communication materials are preserved and can be repeatedly accessed if audiences wish to return to them and that narratives and key messages are consistent across channels. If information changes or new evidence emerges, be transparent about this, explaining what had changed and why. In the longer term, interventions that improve media literacy and numeracy can help people distinguish between truths and false information in the wider information ecosystem.

Proactive promotion: Examples

Climate change

The majority of people in the UK accept that climate change is occurring and is caused by human activity, but a minority continue to believe that the climate is either not changing or that such changes are not caused by humans.

Those who are sceptical are typically quite firm in these beliefs and listen to a relatively small number of scientists and commentators who promote these views. These beliefs may be closely linked to doubts about the trustworthiness of government messaging, and concerns about mainstream science and media.

While not believing in human-caused climate change might mean that these audiences don’t engage in green behaviours, most of the time these beliefs are not likely to be causing immediate harm. For beliefs like these, directly countering false stories and statements about the reality of climate change runs the risk of promoting false stories to a much wider audience, and is unlikely to change the views of climate-sceptic audiences who are committed to their stance.

Instead, a proactive promotion approach might be more effective. This will involve promoting a true, clear, and easy-to-understand narrative that explains how we know that climate change is caused by human activity, citing evidence. It does not need to address specific false claims, but should instead focus on establishing a coherent and consistent explanation that stands alone and is repeated and reinforced over time.

Sanctity of the nation-state in non-democratic regimes

Many governments around the world aim to foster a sense of national pride amongst citizens. In healthy democratic states, this may include activities such as celebrating national holidays, recognising the successes of citizens (e.g. athletes or business leaders), the teaching of national history in schools, and championing the natural beauty of the country.

In non-democratic states, additional or alternative tools are sometimes used, including:

- the suppression of information or news that may undermine the established narrative;

- erasure of past historical events that are inconsistent with the official national story;

- sustained disinformation campaigns to build or retain a certain worldview amongst its citizens and;

- penalties for any individuals or groups who speak out against the official narrative.

Depending on how long such regimes have been in power, citizens living in such countries may have had their entire lives to construct a worldview composed of information that is untrue and incomplete.

The foundational beliefs that makeup someone’s worldview are often considered sacred (non-negotiable truths that people will react strongly against if challenged) and populations in oppressed states are likely to fear reprisal for consuming information that directly conflicts with official narratives. Consequently, a proactive promotion approach is much more likely to be effective in these cases. This will involve providing an accessible, compelling alternative narrative that does not directly conflict with sacred values.

Take, for example, the narrative promoted by Putin of a unified Russian identity, united by a shared language, religion and Soviet history, that encompasses Russians in Russia and the Russian-speaking diaspora living in former Soviet nations. The concept is known as “Russkii Mir” (Russian World).

If a campaign were to try to change these beliefs by dismissing the concept of “Ruuskii Mir” and arguing that many citizens of former Soviet countries do not view themselves as Russian, this would put Russian values in direct opposition to Western values.

In a competition between sacred values and alternative “foreign” values, sacred values will likely win out. Instead, a more successful counter-campaign would focus on promoting other positive values such as democracy, freedom of information and tolerance, without attacking the existence of “Russkii Mir”. In this way, people are able to hold onto both sets of values at the same time (thereby preserving self-esteem and avoiding cognitive dissonance), until a point where they might be able to let go of views that are less grounded in evidence.

Reactive response

For beliefs which are not particularly embedded, but are causing harmful behaviour in the short term, a reactive response (also known as a counter-narrative) approach is recommended.

What is “reactive response”?

Reactive response approaches involve challenging false stories and statements directly, including debunking, fact-checking, and direct rebuttal. In some cases, mythbusting may be suitable as part of a reactive response strategy.

To execute a reactive response strategy, communicators should:

- Quickly and directly address the relevant false stories or disinformation

- Explain in a straightforward way why the story is false (with care taken not to “overkill” it – too many reasons or too strenuous a denial can paradoxically appear less believable)

- Ensure that the truth is set out clearly, and is easy for audiences to understand and remember

- Ensure rebuttal messages are aligned with broader narratives.

Why is reactive response recommended in this situation?

As detailed above, reactive response approaches, particularly mythbusting, carry risks. These risks include amplifying false information, spreading it to a wider audience, creating the perception of a two-sided debate, and triggering reactance in individuals who hold the false belief. This is why it is recommended only when beliefs are not highly embedded, and when there is an immediate risk of harmful behaviour.

When beliefs are non-embedded and likely to lead to harmful behaviours, we can and should intervene. These new or loosely-held beliefs are easier to dispel with direct rebuttal than more embedded ones.

How to design an effective reactive response strategy

Plan and prepare

Identify relevant false beliefs and affected audiences

Publicly debunking falsehoods that are not widely believed, or are only believed by a small minority, can unwittingly amplify them to a broader audience, so it is very important to have a clear understanding of the prevalence of the relevant false belief and the audiences involved.

What to communicate

Provide truthful information

Establish the facts of the situation, and develop them into coherent and consistent communications and campaign materials that explain why the relevant beliefs are false and set out the true facts.

Set out the truth in a way that is easy to understand and recall

When false assertions are simple and memorable and true assertions are complicated or confusing, the false assertions are more likely to stick in the minds of the audience (and memorability, “I’ve heard this somewhere before,” is a common heuristic for truth). When debunking false information, it is important to make sure that the truth is presented in a way that is straightforward, memorable, and easy to understand.

How to communicate

Use non-judgmental language and tone

Avoid messaging that implies that people who believe the false information are foolish, naive, or gullible as if people feel attacked for their beliefs they are likely to reject debunking messages and experience psychological reactance.

Target communications to the relevant audience

Target debunking information to the relevant audience where the false belief is most prevalent, using relevant channels and messengers. Consider the risks of communicating reactive response messages to a broader audience where the false belief may not be widely prevalent.

Avoid presenting falsehoods in a prominent manner

Consider that many people “skim read” mythbusting and debunking materials. If falsehoods are set out in communication and campaign materials in a prominent style that draws the eye while debunking information is less visible (for example, a small label saying “Incorrect” next to a large false statement), people may be left with the impression that the false information is both true and being promoted by official channels.

Use a range of channels, including in-group messengers

Determine which messengers and channels are trusted by the relevant audience, and seek to share debunking messages through these messengers and channels. Ideally, ensure that information is shared through multiple channels that are not perceived as closely aligned by audiences.

Broader considerations

Minimise confusion and noise in the information landscape

Ensure that information and communication materials are preserved and can be repeatedly accessed if audiences wish to return to them and that key messages are consistent across channels. If information changes or new evidence emerges, be transparent about this, explaining what had changed and why.

Reactive response: Examples

COVID-19 ‘cures’

During the COVID-19 pandemic, rumours and false stories circulated on social media about potential “cures,” including garlic, lemon juice, salt water, and medications intended for the treatment of other illnesses. As the disease was new to people, beliefs about cures were also new and not deeply embedded. This false information carried a high risk of triggering immediate harmful behaviours (both consuming “cures” that may be actively dangerous, and shunning medical advice about how to correctly prevent and treat COVID-19).

In this situation, a reactive response approach – directly debunking false claims – was an effective strategy. People didn’t have deeply-held beliefs about cures that they wanted to defend, and immediate and direct rebuttals from the health service helped prevent these beliefs from taking firm hold (among most audiences) and causing further harm.

Storm communication

Reactive response approaches are appropriate in fast-moving situations where beliefs are new and behaviours carry a high risk of harm. In extreme weather situations, such as a storm, people quickly judge and often re-evaluate whether it is safer to stay at home or to leave.

While people in general often have the deeply embedded belief that their home is the safest place to be in a crisis, their belief about the danger of any current storm is constantly changing. To determine whether it is safe to stay put, people may use their senses and/or turn to social media, neighbourhood communications, and official sources.

As such, governments need to apply a reactive response approach when storms are dangerous enough to prompt evacuation. At this point, governments should actively respond to rumours online that downplay danger by providing information about ongoing damage and highlighting others who have evacuated.

Watch and wait

What does “watch and wait” mean?

When beliefs are new and are not particularly embedded among the target audience, and are also not causing any harmful behaviours, watching and waiting can be the most effective strategy.

Watching and waiting involves taking no immediate communication action to dispel a false belief. Instead, communicators should continue to monitor the false belief for signs that it is becoming more embedded or is causing harmful behaviours, in which case a shift in strategy may be required.

Why is watch and wait recommended in this situation?

Disinformation and false stories can create new, non-embedded beliefs. As communicators, we are biased toward action, mythbusting and correcting as soon as we can. At times, however, this can lead to amplifying misinformation rather than correcting it. If the belief is unlikely to cause harmful behaviours we might therefore want to consider taking no action. We might instead adopt a monitoring approach, tracking whether the belief is spreading further or leading to harmful behaviours.

Watch and wait: Examples

Astrology

Astrology is an example of a false belief that some audiences entertain for pleasure. Among a minority of audiences, it may be a highly embedded belief (coinciding with other beliefs in supernatural forces), but in the general population, astrology is either ignored or tentatively believed as a way to derive personal insight and entertainment. In the vast majority of cases, a loose belief in astrology is unlikely to lead to immediate harmful behaviours.

In this case, then, monitoring and waiting are likely to be the most effective strategy. No government in the world (to our knowledge) has implemented a counter-astrology campaign, despite it being a widely-held false belief. If astrology began to trigger harmful behaviours, then a shift in strategy should be considered.

Don’t swim after eating

Another common false misconception in the UK (and other countries) is that eating before swimming can cause cramps. To reduce drowning risk, parents therefore commonly tell their children that they should not swim immediately after eating. Existing evidence however suggests that no such danger exists: cramps are not more likely immediately after eating.

This belief is unlikely to be deeply embedded, as it does not typically form part of a wider worldview. Waiting for thirty minutes before swimming is not harmful, and thus the most effective strategy for this type of misconception is typically monitoring and waiting, taking no immediate action.

Section 3: Using the Wall of Beliefs to develop communications plans

When false beliefs or disinformation narratives are detected

If a false belief or disinformation narrative is causing concern, we advise the following approach, drawing on the “Wall of Beliefs” model and strategy matrix.

Step 1: Explore the wall

The first step is to determine where the belief fits within the “Wall of Beliefs” of your target audience.

You can use user research, focus groups, academic literature, media stories, and/or other public information sources to find out whether the belief is part of a broader worldview, and how it links to other beliefs.

You can explore which beliefs it commonly coincides with and whether it fits within a wider narrative that is understood and believed by the target audience.

Step 2: Discover belief strength

The next step is to determine how embedded a belief is within the “Wall of Beliefs” of your target audience.

You can use similar sources to determine whether beliefs are newly adopted or long-embedded, whether audiences feel particularly strongly about them, whether they fit into broader false narratives, and whether people feel a personal connection to the belief.

Step 3: Explore the risk of harm

The third step is to determine the harm caused, or risk of harm posed, by the belief or set of beliefs in question.

You can consider whether a belief is causing people to engage in risky behaviours, or to shun protective behaviours, and whether these harmful behaviours are widespread or rare among the target audience.

Step 4: Use the strategy matrix

The fourth step is to use the strategy matrix to explore the most suitable communications approach, depending on the quadrant in which the belief falls.

If the belief falls in different quadrants for different audiences, it may be necessary to consider a combined approach, targeting different communications at different audiences.

Step 5: Develop a response plan

Use the principles from the corresponding section(s) of the strategy matrix to develop a communications response plan, and policy response if required to manage behaviours.

When harmful, belief-driven behaviours are detected

In some circumstances, harmful behaviours (or harmful absence of behaviours) might be identified first, with policymakers suspecting that these are influenced by false beliefs. In this case, it is necessary to first determine which beliefs are influencing the harmful behaviour, before assessing the appropriate strategy to counter them.

Step 1: Determine beliefs influencing behaviour

The first step is to identify which beliefs are influencing the harmful behaviour of interest.

You can use primary research, existing research, media stories, and/or other public information sources to identify key beliefs that are influencing the behaviour of interest.

Step 2: Explore the wall

The second step is to determine where such a belief might sit within the “Wall of Beliefs” of your target audience.

You can use user research, focus groups, academic literature, media stories, and/or other public information sources to find out whether the belief is part of a broader worldview, and how it links to other beliefs.

You can explore which beliefs it commonly coincides with and whether it fits within a wider narrative that is understood and believed by the target audience.

Step 3: Discover belief strength

Determine how embedded a belief is within the “Wall of Beliefs” of your target audience.

You can use similar sources to determine whether beliefs are newly adopted or long-embedded, whether audiences feel particularly strongly about them, whether they fit into broader false narratives, and whether people feel a personal connection to the belief.

Step 4: Use the strategy matrix

The fourth step is to use the strategy matrix to explore the most suitable communications approach, depending on the quadrant in which the belief falls.

If the belief falls in different quadrants for different audiences, it may be necessary to consider a combined approach, targeting different communications at different audiences.

Step 5: Develop a response plan

Use the principles from the corresponding section(s) of the strategy matrix to develop a communications response plan, and policy response if required to manage behaviours.

Example: increasing electoral participation among minority groups

In your country, certain minority groups have a long-standing history of low electoral participation. In recent years, electoral participation has fallen further. You are tasked with increasing electoral participation among these minority groups in the upcoming election.

- Establishing the wall of beliefs: Using information sources, you identify key beliefs that may keep members of the minority group from voting.

- Determining how embedded a belief is: You estimate the strength and prevalence of the different beliefs. Given that voting participation is a long-standing issue, some beliefs are likely deeply embedded. Since the voting share has recently declined further, it is also possible that some new beliefs are also influencing limiting electoral participation.

- Determining where these beliefs fit in the strategy matrix: Among the more deeply embedded beliefs, you can identify which ones play a key role and seem like they would respond to a proactive promotion approach. Perhaps there is a belief that “the Government doesn’t represent people like me”, which might be easily influenced by a campaign highlighting parliament members belonging to the minority group in question. Among the less embedded beliefs, determine which are likely to be most damaging to electoral participation, so you can explore countering these directly.

- Developing your communications and policy response: Because the challenge is long-standing and complex, you will likely need to combine approaches from the different quadrants. You can promote behaviour change without targeting beliefs by simplifying the voting process, tackle harmful but less embedded beliefs with a “reactive response” approach, and deliver a proactive promotion campaign to target the most embedded beliefs over the medium to long term.

The boundaries of the Wall of Beliefs

Information ecosystems

The Wall of Beliefs sheds light on the psychological motivations of people who believe in or share mis/disinformation, and why the social origins of people’s beliefs play an important part in determining how best to counter them.

However, social relationships and identities are not the only factors determining how hard a particular belief is to counter or debunk. The infrastructure, tools, and platforms through which information is shared and consumed – shaped by the market forces behind them – also have a significant influence on beliefs and the success of interventions to change or challenge them. The role of these external influences is covered extensively elsewhere.

For further reading, see:

- Research note: Examining how various social media platforms have responded to COVID-19 misinformation

- Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures

- The digital transformation of news media and the rise of disinformation and fake news

- The Attention Merchants by Timothy Wu (book)

Motivation to spread false beliefs

The Wall of Beliefs explores why people adopt or sustain beliefs, but does not explore the motives and behaviours of those who spread falsehoods and persuade others to adopt false beliefs.

There are many reasons why people share untrue stories and spread falsehoods. In some circumstances, people share false information without much consideration, especially when the information seems “plausible enough.” In others, they may genuinely believe false information and wish to alert others to perceived dangers or conspiracies. People might also share false information to gain approval or acceptance by others who share similar worldviews, even if they are not fully convinced of the veracity of the information.

Some may choose to spread false or conspiratorial beliefs on purpose in an attempt to sow mistrust, undermine true information, or stoke division, sometimes in the pursuit of specific goals. People who purposely spread stories they know to be false (or do not care to verify) may not be interested in challenging or reconsidering their stated beliefs, as their goal is neither to convince others nor to discover the “truth,” but to muddy the information landscape.

References

- Bem, D. (1967). Self-Perception: An Alternative Interpretation of Cognitive Dissonance Phenomena. Psychological Review, 74, 183-200.

- Claesson, A. (2019), Coming Together to Fight Fake News: Lessons from the European Approach to Disinformation, Center for Strategic and International Studies. Accessed July 2022.

- Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (S.I. 2010/2703). Accessed July 2022.

- Coolican, S. (2021), The Russian Diaspora in the Baltic States:, LSE Ideas. Accessed July 2022.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (2021), Improving Public Messaging for Evacuation and Shelter-in-Place. US Department of Homeland Security. Accessed July 2022.

- Frankfurt, H. (2005) “On Bullshit”, Princeton University Press.

- GOV.UK (2015), The Civil Service Code, Statutory Guidance.

- Hammond, C. (2013), Can you swim just after eating? BBC Future. Accessed July 2022.

- Krishnan, N., Gu, J., Tromble, R., Abroms, L. (2021) Research note: Examining how various social media platforms have responded to COVID-19 misinformation. Harvard Kennedy School, Misinformation Review.

- Martens, B., Aguiar, L., Gomez-Herrera, E., Mueller-Langer, F. (2018) The digital transformation of news media and the rise of disinformation and fake news. European Commission, JRC Digital Economy Working Paper 2018-02.

- Munn, L. (2020). Angry by design: toxic communication and technical architectures. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 7, 53.

- Pennycook, G., Rand, D. (2021) The Psychology of Fake News, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Volume 25, Issue 5.

- Statista (2021), Number of passengers travelling on the Eurostar and Le Shuttle in the United Kingdom (UK) from 1994 to 2020. Accessed July 2022.

- Wanless, A. (2022), One Strategy Democracies Should Use to Counter Disinformation, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Accessed July 2022.

- Wu, T. (2017) The Attention Merchants. Atlantic Books.

- YouGov tracker (2022), Belief in climate change. Accessed July 2022.