GCS Evaluation Cycle

Continuing Professional Development (CPD) points: 2

The GCS Evaluation Cycle provides a flexible framework for measuring success across all communication activities, promoting continuous learning and innovation while integrating best practices for better impact and future planning.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle supersedes the Evaluation Framework 2.0.

Use the Evaluation Cycle campaign template to plan and track your campaign evaluation in a digestible, easily sharable format.

Table of Contents

- Foreword by Chief Executive

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- The GCS Evaluation Cycle

- Stages of Evaluating Communication Activities and Campaigns

- Learning and Improvement: the Core of the Evaluation Cycle

- Evaluating different types of communications

- Paid-for Campaigns vs Low/No-cost Communications

- The Stages of Evaluation In Detail

- Example of Evaluation Metrics: from Stage 1 to 6

- Linking the Evaluation Cycle and OASIS

- Building in Inclusivity and Audience Segmentation

- Linking the Evaluation Cycle to COM-B for Behaviour Change

- Additional Considerations

Foreword by Simon Baugh, Chief Executive of Government Communication Service

Given that evaluation is the cornerstone of effective communications, I am excited to introduce the new Evaluation Cycle for government communications. This has evolved from the solid foundation and best practices established by its predecessor, the Evaluation Framework 2.0. After undergoing independent review and engaging in thorough discussions with stakeholders, key areas for advancement have been identified and incorporated into this new model.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle has been designed to reflect changing audience demographics, to integrate digital advancements and to be a tool for ongoing learning and development. It outlines a clear, structured process that empowers communication professionals to meaningfully evaluate all types of communication activity, measure the impact of their work accurately and seek effective ways to improve. This way, government communications will not only reach target audiences, but also resonate with them in a more meaningful and cost-effective way to drive behaviour change.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle aims to spark a never-ending journey of learning, innovation, and progress. By positioning evaluation as an intrinsic element of communication planning from the outset, we will ensure valuable insights are used to inform what works and what doesn’t from the very start of a communications campaign, however large or small. This is crucial for communicators to make informed decisions fuelled by evidence.

Other updates in this framework include the emphasis on “real-time” evaluation – by using our digital capabilities to collect data in real time to optimise communication outputs. Additionally, the new framework emphasises audience inclusivity, ensuring we better understand and target underserved audiences in line with our Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan.

This new GCS Evaluation Cycle will help us shift our focus further to building on data and insights, supporting all GCS communicators in driving creative innovation and delivering impactful results.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to those who originally drafted and developed the GCS Evaluation Framework and all those who have reviewed and offered comments and ideas on the new GCS Evaluation Cycle.

Thanks also to members of the GCS Strategy and Commitment Board, the GCS Heads of Discipline, the GCS Data, Insight and Evaluation forum, GCS Directors of Communications and the Cabinet Office Evaluation Task Force. Particular thanks to Professor Kevin Money (and associates), Dr Becky Tatum, Clement Yeung, Dr Amanda Svensson, Dr Moira Nicolson, Robin Attwood, Neil Wholey, Ethan Carlin and Pamela Bremner.

This guide draws heavily from the academic works of Professor Kevin Money et al. of the Henley Business School at the University of Reading along with a number of key outputs and publications. For details, see reference list.

List of Abbreviations

| AMEC | International Association for Measurement and Evaluation of Communication |

| COM-B | COM-B Model: Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, & Behaviour |

| GCS | Government Communication Service |

| KPI | Key performance indicator |

| OASIS | OASIS Framework: Objectives, Audience/Insights, Strategy/Idea, Implementation, & Scoring/Evaluation |

| ROI | Return on investments |

| ToC | Theory of Change |

Introduction

Evaluation of government communications is essential for improving policy outcomes, adapting innovative strategies, promoting learning, demonstrating value, and building public trust. By measuring the impact of communication efforts, government organisations can refine their messaging, allocate resources effectively, and enhance the overall effectiveness of their communication campaigns.

The updated GCS Evaluation Cycle is designed to provide best-practice guidance for GCS colleagues to most effectively and efficiently evaluate communication activities across government.

Purpose and Vision

The new GCS Evaluation Cycle outlines the steps and processes you need to plan and execute your evaluation, whether it is for major paid-for campaigns or low/no-cost communication activities. It builds on the foundations of the previous Evaluation Framework 2.0 but embraces a more dynamic and process-driven foundation which:

- Emphasises the importance of continuous learning, innovation and improvement.

- Integrates close links to other frameworks such as OASIS.

- Outlines metrics that can be applied across all types of communication activity.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle encompasses industry-leading practices that will continue to drive improvements across the profession, enabling communicators to demonstrate the value and impact of campaigns and communication activities. It equips communicators to effectively measure success while appraising learnings that will improve planning, design and impact of future communications.

Evaluation Evolution

The GCS Evaluation Cycle provides information and guidance about which metrics to measure and what aspects to consider when planning and delivering a comms evaluation. This includes defining your communication objectives, considering the characteristics of your target audience, linking metrics to assess the impact of your communications, and identifying learnings. As each evaluation caters to different audience groups, communication objectives and more, this Cycle does not aim to be one-size-fits-all. Evaluators should assess the characteristics of your communication activity and take guidance from this Cycle where appropriate.

This guide will help you to:

- Embed evaluation upfront as a core element in every communication plan.

- Identify the consistent metrics used to measure different types of campaigns and low/no-cost communication activities.

- Understand the different aspects to consider when planning and delivering an evaluation for communication activities.

- Identify and consider audience characteristics and difficult-to-reach audiences to ensure audience inclusivity.

- Build clear connections between evaluation and other relevant GCS frameworks (e.g., OASIS, Theory of Change and COM-B for behaviour change).

- Measure campaign success, both in real-time and throughout the campaign or communication activity.

- Identify how evaluation results can contribute to the continuous improvement of corporate objectives and reputation management.

- Explore outside of existing ways of working to devise innovative solutions to address challenges more efficiently and effectively.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle replaces the GCS Evaluation Framework 2.0 and is an evolution that still includes the familiar evaluation components and metrics. However, these components and metrics have been updated to acknowledge and account for the evolving communications and audience landscape.

Building on Cross-Government Expertise and Guidance

The Magenta Book is HM Government’s guidance document that details how to scope, design, conduct, use and disseminate evaluations. It explains how to incorporate evaluation through the design, implementation, and review stages of policymaking. Building on cross-government expertise on policy evaluations, the GCS Evaluation Cycle optimises the use of these evaluation principles for communication evaluations, making sure that target audience groups are reached and that behavioural science principles are considered.

The Magenta Book includes transferable concepts that apply to both policy and communication evaluations, GCS colleagues are recommended to utilise the Magenta Book alongside the Evaluation Cycle. This is so they can gain an understanding of an array of evaluation methods for different scenarios, things to look out for when conducting quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis, and guidance around how to share evaluation results and use these results to inform better communications in the future.

The GCS Evaluation Cycle

Stages of Evaluating Communication Activities and Campaigns

The GCS Evaluation Cycle is an agile framework for continuous assessment, rather than a linear evaluation. The agile nature of the Evaluation Cycle means you can utilise the aspects most relevant to your type of communication activity.

However, it is still important that a consistent set of metrics are used to measure the effectiveness of your communication activity. Consistent use of these metrics helps with choosing appropriate objectives for your communication activity and setting targets to measure success, such as key performance indicators (KPIs), to be established and tracked. Metrics are divided into inputs, outputs, outtakes and outcomes, in line with definitions widely used by AMEC and other professional bodies. Impact then summarises how the communication outcomes contribute to organisation and policy objectives. Finally, to intrinsically link the evaluation process to continuous learning and improvement, learning and innovation is embedded at the final stage of the cycle to capture strategic learnings that drive new ideas, learnings and improvements that can be taken forward. Learning and innovation should be linked back to the start of your communication planning, the Inputs phase.

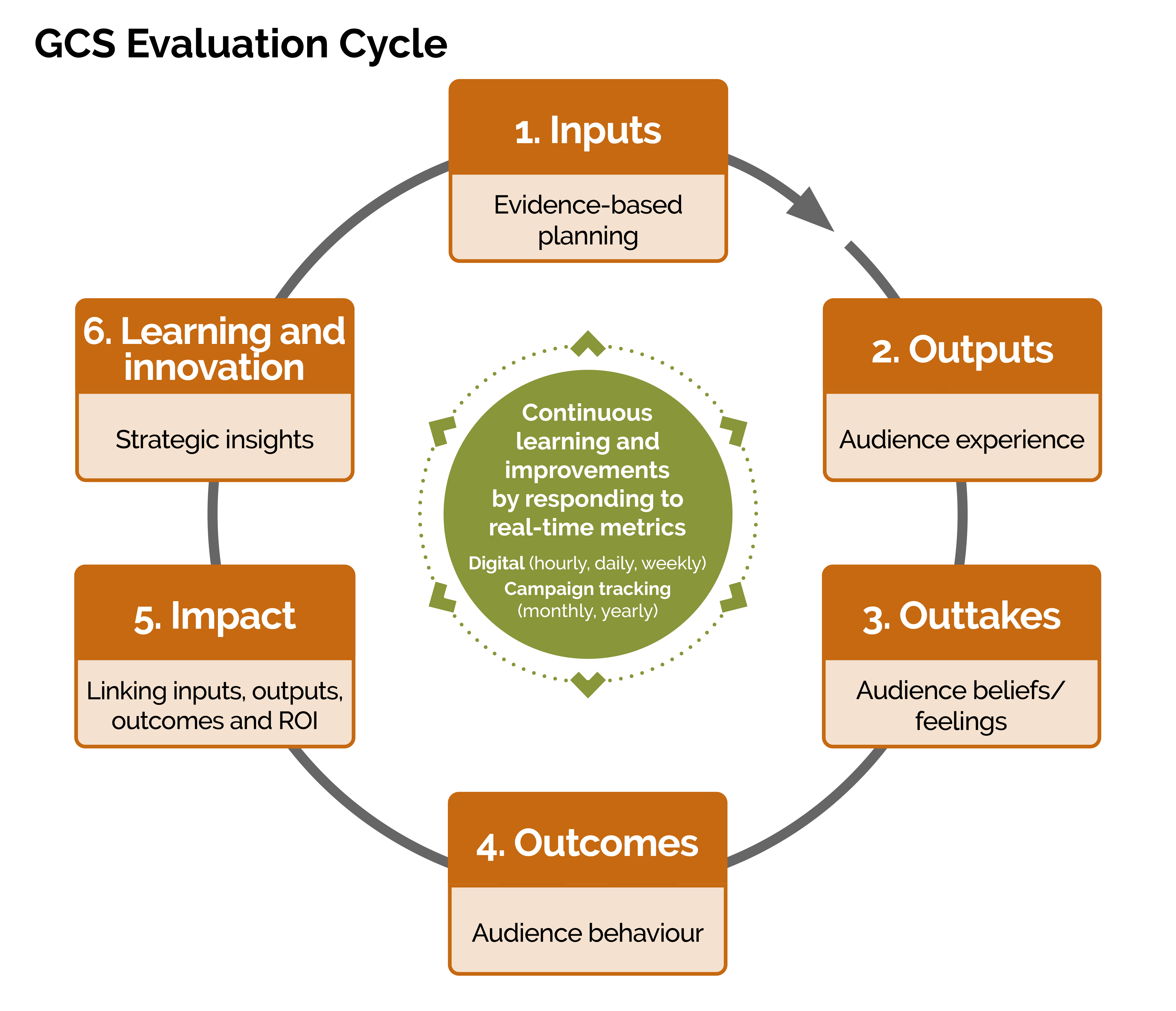

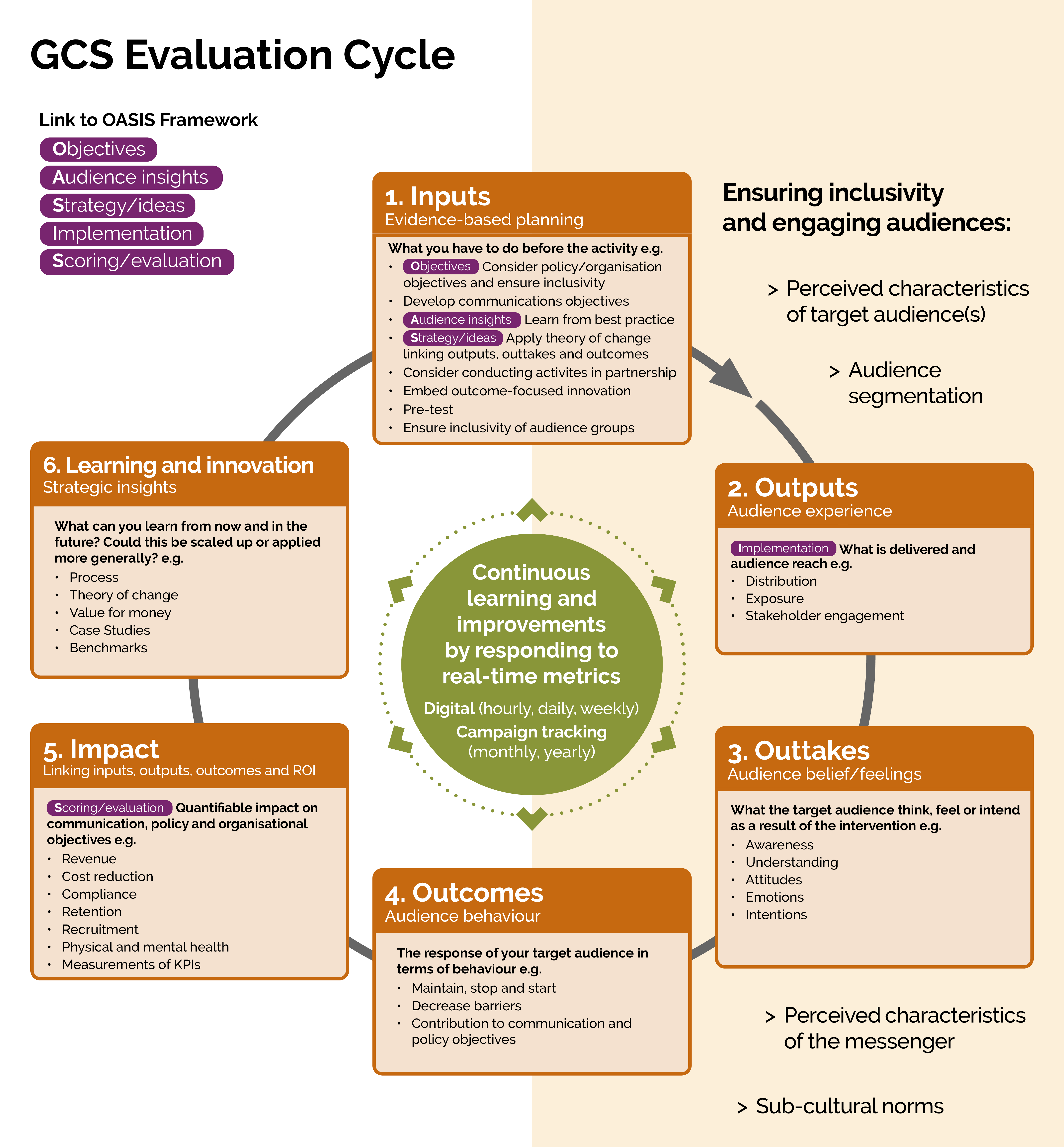

Therefore, the Evaluation Cycle consists of six stages:

- Inputs – what you put in: evidence-based planning and content creation.

- Outputs – audience experience: the experience you delivered and created for your audience through the reach of your communications.

- Outtakes – audience perceptions: what they think, feel or intend to do because of your communication activities..

- Outcomes – audience behaviour: response from and/or behaviour of your audience.

- Impact – what you achieve: in terms of organisation and/or policy objectives and KPIs.

- Learning and Innovation – what you play forward: the lessons you take forward to improve the current or future communication activities.

Learning and Improvement: the Core of the Evaluation Cycle

At the core of the Evaluation Cycle sits continuous learning and improvement. This marks the most crucial part of the model, as it defines the purpose of evaluating our communication – to learn and to improve. Learnings should be informed by things that went well and things that did not go so well to feed into current and future planning and implementation.

Continuous Learning and Improvement – You should consider how measuring real-time digital metrics throughout your communication activity can generate new insights and thus potential improvements for the communication activity. If possible, you should implement these improvements to your communications when it is still ongoing. Guidance around delivering digital communications can be found in the Digital Discipline Operating Model.

Learning and Innovation – Digestible lessons should be packaged up for use in the future. The learnings generated should feed back to inputs (stage 1 of the circular model) of a new evaluation cycle, so that any new communication activity can take on these lessons learnt. Learnings that can be applied or scaled more generally should be shared across government.

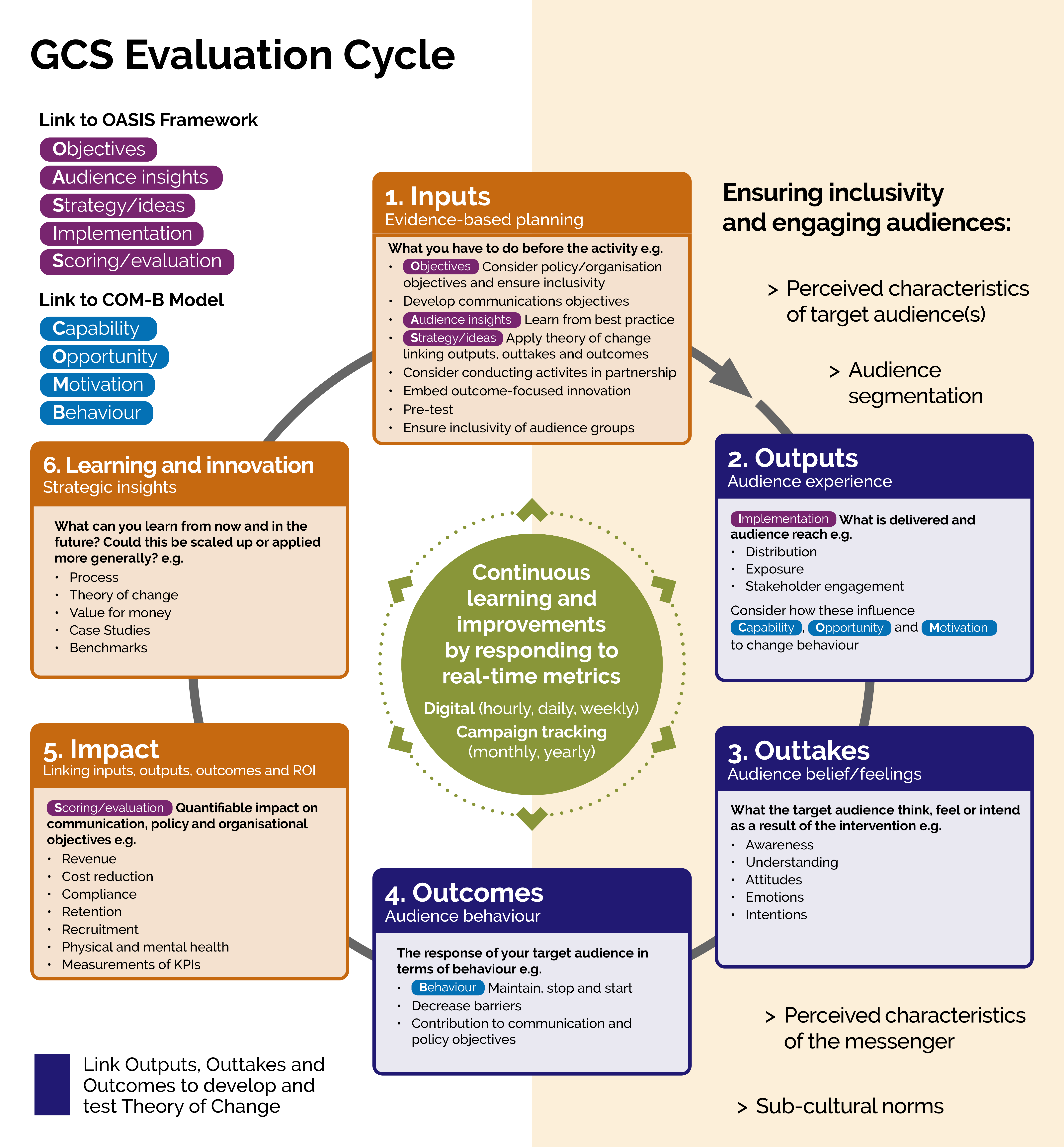

Diagram A illustrates the GCS Evaluation Cycle, which defines evaluation as a recurring process.

Evaluating different types of communications

Different communication activities aim to engage the audience in different ways. Here are three categories of engagement goals:

- Goal 1: Awareness and attitudes

In the minority of cases, communications might primarily seek to raise awareness of an issue or to change people’s attitudes, with no behaviour changes anticipated, meaning measurement of Outcomes may not always be possible. However, even where the communication activity does not have a primary behavioural element, considerations should be made regarding how the communication objectives of increasing awareness or changing attitudes feed into overarching behavioural and policy objectives (more details on this are outlined in the Inputs section). - Goal 2: Behaviour Change

Most government communication seeks to change behaviours to implement government policy or improve society. This means that, in addition to tracking awareness metrics, evaluations should capture whether your target audience adopt the desired behaviour change, according to the purpose of “start”, “stop” or “maintain”. This is so that we can learn which methods, messages and channels are effective for encouraging successful behaviour change. - Goal 3: Recruitment

Recruitment is a specific form of behaviour change where people are encouraged to start an activity. This category encompasses major employment campaigns into public sector jobs rather than recruiting people to “register” or “take part”. Successful recruitment into public sector jobs is vital to maintaining public services and protecting the country. Recruitment campaigns for jobs such as teachers, nurses, and the armed forces share many characteristics, unique demands and broader societal impact, and thus benefit from a dedicated category.

Paid-for Campaigns vs Low/No-cost Communications

The GCS Evaluation Cycle has been designed for any type of communications and campaigns, from low/no cost to paid-for campaigns.

For low-cost or no-cost campaigns: You should measure metrics most suitable to your communication activities at each stage.

For paid-for campaigns:

- GCS recommends that approximately 5-10% of total campaign resources are allocated to evaluation. Communicators should dedicate this to research and optimisation which can include both in-house and outside agency research. Paid-for campaigns are advised to measure as many of the suggested metrics as possible.

- GCS encourages all departments and organisations to spend up to 10% of their existing campaign budget on innovative techniques which we can test, ensuring we can continue to use public funds responsibly and judiciously whilst seizing new opportunities.

The Stages of Evaluation In Detail

1. INPUTS

What are inputs?

Inputs are what you put in at the start – the planning and research that informs your communications or campaign.

This includes everything that must be done to prepare for the communication activity, which may include conducting research, reviewing previous learnings, planning evaluation design, determining budget and costs, etc.

Wherever possible, planning should be based on research evidence, insights and learnings to maximise your chance of delivering a successful campaign or communication activity. Successful communication activities and campaigns rely upon sufficient preparation.

What are they used for?

- To detail and reflect on what has been done to enable the communication activities.

- To demonstrate that communications are based on evidence-based planning, research and previous strategic learnings.

- To provide context for the outputs, outtakes and outcomes the campaigns generate so they can be evaluated in line with the budget and resources put into the communications activity.

- To ensure clear links to policy and communication objectives and development of appropriate KPIs.

- To make predictions and assumptions of how your communications Outputs would lead to Outtakes, Outcomes and ultimately Impact, one step at a time.

- To consider innovative solutions and determine in what ways and how frequently these are evaluated during implementation.

What’s included in INPUTS – Setting Objectives

Your communications objectives should be set out according to the SMART principles:

- Specific: clearly define what you want to achieve.

- Measureable: determine a baseline and identify ways to track your progress.

- Achievable: set targets that are challenging but also realistic.

- Relevant: ensure your objectives align with your policy and organisation objectives.

- Time-bound: set a deadline for achieving your objectives.

To enable effective evaluation, your SMART objectives must:

- Establish a current baseline measure if no communication activity were to take place.

- Set challenging targets that forecast the change your communication activity will make over a defined period of time.

- Provide an explanation for the level of change being targeted.

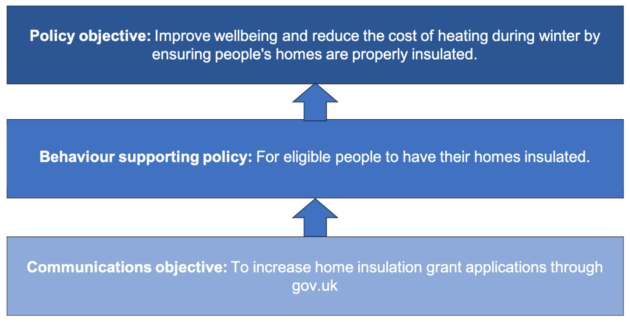

To ensure your communication objectives are relevant they must be coherent to the aims and vision set out by your policy and organisational objectives. Consider questions like:

- How do your communication objectives feed into the policy and organisation objectives?

- How do your communication objectives feed into the specific behavioural changes required for the policy to succeed?

- Does your communication activity reflect your organisation’s culture, values, and corporate objectives?

This is an example of different types of objectives and how they feed into the overall policy objective in a bottom-up manner.

For paid-for campaigns: You must set KPIs, a quantifiable measure which allows you to monitor progress towards your objectives throughout the campaign. The GCS SMART Targets Tool is designed to support campaign teams in setting challenging yet achievable KPI targets.

What’s included in INPUTS – Communication Planning

You should make sure your communication plan covers the following considerations so you can be best prepared for the forthcoming stages in the Evaluation Cycle. This is not an exhaustive list, and you should expand on areas that matter most to your communication activity.

- Embed in your OASIS plan

- The OASIS campaign planning guide provides government communicators with a framework for preparing and executing effective communication activities. Within OASIS, Objectives and Scoring are especially important for the purpose of evaluation.

- For more information on OASIS for evaluation, please refer to the section Linking to OASIS.

- Ensure inclusivity of audience groups

- Are you using behavioural insights to understand the target audience of your communication activity?

- Have you considered how activities will serve those with protected characteristics?

- Have you considered audience segmentation to help target your communications?

- Learn from best practice

- What has been learned from previous communications activities?How can you build upon previous performance?

- Who has done similar types of work before?

- What are the keys to success?

- What things have others tried that did not work?

- Apply Theory of Change and COM-B where applicable, e.g., for a behaviour change campaign (you can learn more about Theory of Change and how to incorporate the COM-B model for behavioural considerations).

- Consider whether your target audience has the capability, opportunity and motivation to change their behaviour to identify the barriers these present and how your communications might need to overcome them.

- What beliefs/feelings would you like your audience to have?

- What audience behaviour would you anticipate?

- How will your Outputs lead to your Outtakes, Outcomes, and ultimately Impact?

- Consider conducting activities in partnership

- What are the strengths of other organisations that you can capitalise on?

- What reputations would you favour in your partnership organisations?

- Can we work with other brands or organisations that have existing audience loyalties?

- Embed outcome-focused innovation

- While existing methods might work adequately, are there new promising ways to deliver the communication objectives more productively, more effectively, or at a lower cost?

- How can we best take advantage of emerging technologies?

- How can we best adapt to evolving audience trends?

- Pre-test/pilot

- Can your communication activity be piloted with a small audience sample?

- What metrics and opinions are you tracking and seeking in order to identify unintended consequences and serendipities?

| Examples of evaluation metrics for Inputs (not an exhaustive list) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of communication | Examples | |||||

| Awareness | Behaviour change | Recruitment | Metric | Medium | Definition | Measurement Method |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Total spend to date | Online and/or Offline | Aggregate total spend so far (online and offline) – How much money has been spent on digital media? – Sum of one-off set up costs (see AMC guidance) and periodic offline media spend updates | £ |

| ✔ | Theory of change (including evidence base) | N/A | Implementation of behavioural science in planning effective communication | Is it in place?Is it evidence-based? | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Content creation | Online and/or Offline | Infographics, video, etc. | Volume by type |

| ✔ | Volume of press releases | Offline | # of press releases sent out | # of press releases sent out | ||

| ✔ | Volume of social media releases | Online | # of releases to owned social media channels | # of releases to owned social media channels | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Insights and Formal Learnings | Offline | Implementation of insights from research and/or learnings from previous evaluations | Is it in place?What did it inform? |

2. OUTPUTS

What are Outputs?

Outputs are objective measurements of what is delivered and how your audience encounters and interacts with your communications through reach, distribution and exposure. This captures how successfully your communication activity has reached your target audience, which may include press coverage, public relations and impressions, as well as low/no-cost activities such as stakeholder engagement.

If the campaign has a behavioural change element, links should be made to the COM-B model. This allows you to consider the reach, distribution and/or exposure of your communications in relation to audience experience and how this influences capability, opportunity and motivation among your target audience. For example, how an Output might lead to a change in opportunity. (See more details about COM-B.)

What are they used for?

By tracking Output metrics around target audience reach, you can determine how effective your communications or campaign approach was in reaching your target audience. Tracking assets and collateral allows you to evaluate messaging, asset type and test implementation of your communications plan, i.e. which channels were most successful at reaching your target audience or different audience segments.

| Examples of evaluation metrics for Outputs (not an exhaustive list) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of communication | Examples | |||||

| Awareness | Behaviour change | Recruitment | Metric | Medium | Definition | Measurement Method |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Estimated total reach | Online and/or Offline | Aggregate audience reach | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Estimated offline reach | Offline | Reported audience reach for offline media | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Reported online reach | Online | Estimated reach as reported by digital platforms | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | Direct contacts | Online and/or Offline | # of direct on/offline contacts, e.g., electronic direct message | Absolute number of proportion of target audience | ||

| ✔ | Events organised | Offline | Volume of events | # of events; # of attendees, feedback from attendees | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Volume of coverage | Online and/or Offline | # exposures | # press cuts; # of broadcasts (local/national) |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Partnerships secured | Offline | # of partnerships providing amplifying support | Formal sign-up to either actively promote and amplify campaign material or make any form of value in-kind partnership or financial contribution |

3. OUTTAKES

What is an Outtake?

The audience perception – what they think, feel or intend to do as a result of your communication activities. Outtakes capture the reception, perception, intentions and reaction of your target audience to your communication activity. Outtakes are distinct from outcomes: while outtakes focus on audience beliefs, attitudes and feelings, outcomes focus on actual changes in behaviours.

What are they used for?

Outtake metrics measure how your communication activity impacts your target audience’s awareness, understanding, attitudes, emotions, or intentions. Comparing Outtakes with the targets set in objectives enables you to understand which messaging has been effective for engaging your audience or different audience segments.

| Examples of evaluation metrics for Outtakes (not an exhaustive list) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of communication | Examples | |||||

| Awareness | Behaviour change | Recruitment | Metric | Medium | Definition | Measurement Method |

| ✔ | Sentiment – attitudes and emotions | Online and/or Offline | Qualitative and quantitative sentiment. Degree to which a message has been positively or negatively received | % and/or case studies Assessment of press coverage | ||

| ✔ | Passive engagements | Online | The % of impressions generating an interaction (share/like/retweet) | A “one-click” interaction | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Active engagements/ interactions | Online | The % of impressions generated an interaction (comment/response/quote) | Something that involves proactive engagement (e.g., number of words typed) |

| ✔ | Click-through rate | Online | The proportion of impressions generated by a click-through | % | ||

| ✔ | View-through rate | Online | The proportion of impressions meeting a minimum view-through percentage | % | ||

| ✔ | Dwell time | Online | The average length of time spent on a campaign site | Minutes and seconds | ||

| ✔ | Bounce rate | Online | % of site visitors that navigate no further than the landing page | % | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Prompted campaign recognisers | Offline | The proportion of target audience that recalls seeing the campaign when prompted | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Unprompted campaign and issue awareness | Offline | The number and proportion of target audience that has unprompted campaign issue awareness (# and %) | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | ✔ | Experience of different messages that relate to aspects of the Theory of Change | Online and/or Offline | The extent to which different groups agree/disagree with messages related to the Theory of Change | 5-point scale (agreement or disagreement with aspects of message) | |

| ✔ | ✔ | Understanding of campaign content | Offline | Assessment of audience’s understanding of the campaign content. | Qualitative or quantitative assessment to represent overall level of understanding in target audienceHighlight specific content with low understanding. | |

| ✔ | Sentiment towards profession | Offline | The regard in which the profession is held by the target audience or general public | 5-point scale recommended (from strongly positive to strongly negative; don’t know) | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | Agreement | Offline | The number and proportion of target audience that agree with the campaign message | 5-point scale recommended (from strongly agree to strongly disagree; don’t know) | |

| ✔ | ✔ | Stated or intended behaviour change | Offline | The proportion of target audience that claim they will act in accordance with campaign aim | Absolute number and proportion of target audience | |

| ✔ | Expression of Interest (EOI) | Online and/or Offline | The number of people actively expressing interest in applying | Absolute number and proportion of target audience | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Reputation perception | Offline | See later guidance on reputation | See later guidance on reputation |

| ✔ | ✔ | Response rate | Online and/or Offline | % of contacts who respond | % of contacts who respond | |

| ✔ | Intra-profession advocacy | Offline | The degree to which current professionals would recommend the job to friends/family | 5-point scale recommended (from strongly agree to strongly disagree; don’t know) | ||

| ✔ | Influencer advocacy | Offline | The degree to which important influencers (e.g., parents) would support entry to profession | 5-point scale recommended (from strongly agree to strongly disagree; don’t know) | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | Attitudinal change | Online and/or Offline | Degree to which people’s attitudes has changed in favour of the campaign | 5-point scale recommended (from strongly agree to strongly disagree; don’t know) | |

4. OUTCOMES

What is an Outcome?

Outcomes are the response from your target audience in terms of changes in behaviour or active engagement, i.e. registrations to a website/service, adoption of positive habits, cessation of unwanted practices to comply with new laws/regulations, etc. It captures whether your audience’s feelings and motivations (“Outtakes”) really translate to actual behavioural change (“Outcomes”).

What are they used for?

Outcomes determine how your communication activity influenced behaviour change and contributed to the policy objectives, i.e. whether your campaign encouraged your target audience to start doing something, stop doing something or maintain behaviour.

Outcomes enable links to be made between any Outtakes (changes in beliefs and attitudes) and the resulting desired change in behaviour. Remember, even if your communication is primarily aimed at changing beliefs/feelings (“Outtakes”), rather than behaviours (“Outcomes”), you should still consider whether (and if so, how) audience behaviour might change in response to your communications.

| Examples of evaluation metrics for Outcomes (not an exhaustive list) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of communication | Examples | |||||

| Awareness | Behaviour change | Recruitment | Metric | Medium | Definition | Measurement Method |

| ✔ | Behaviour change – maintain, stop or start | Offline | The number and proportion of target audience that has changed behaviour | Absolute number and proportion of target audience | ||

| ✔ | Applications/ sign-ups | Online and/or Offline | Number of completed applications or registrations | Absolute number and proportion of target audience | ||

| ✔ | Completion / registration rate | Online and/or Offline | The proportion of contacts or impressions that go on to complete sign-up/registration | % | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Decreased barriers to change behaviour as targeted by your campaign | Online and/or Offline | Extent to which barriers to desired behaviour were removed or decreased (i.e. increased confidence or opportunity to do behaviour) | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Decreased barriers to behaviour change that were not targeted by your campaign or cannot be change through communications | Online and/or Offline | Extent to which barriers to desired behaviour not targeted by the campaign were removed or decreased, to measure what else is influencing your metrics (i.e. costs or policies you are unable to change through communication) | Absolute number and proportion of target audience |

| ✔ | EOI/applicant conversion | Online and/or Offline | The proportion of EOIs that go on to be applicants | % | ||

| ✔ | Applicant/recruit conversion | Online and/or Offline | The proportion of applicants that go on to be employed | % | ||

5. IMPACT

What is Impact?

Impact draws links between inputs, outputs, outtakes, and outcomes to determine how your communication activity has contributed to or impacted policy and organisational objectives. Impact is the comparison of actual outcome data with KPIs and objectives set to measure whether these were met.

Organisational objectives are distinct from the policy objectives and include longer-term or wider considerations such as ROI, revenue, cost reduction, compliance, retention, recruitment, positive contributions to physical/mental health, environmental impact, etc.

What are they used for?

Impact allows you to demonstrate whether your objectives were delivered. For paid-for campaigns you should also demonstrate whether your KPIs were met and if they were sufficient to deliver the targets set in your objectives. You should also consider how your communications activity contributed to broader organisational impacts.

See further information in the section on measuring ROI and organisational reputation.

| Examples of evaluation metrics for Impact (not an exhaustive list) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of communication | Examples | |||||

| AWARENESS | BEHAVIOUR CHANGE | RECRUITMENT | Metric | Medium | Definition | Measurement Method |

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Comparison with KPIs and objective | N/A | Contribution to policy and/or organisational objectives | Absolute number and proportion of targets met |

| ✔ | ✔ | Long-term compliance or retention | N/A | Contribution to long-term or ongoing policy and/or organisational objectives | Absolute number and proportion of targets met over time | |

| ✔ | Recruits | Offline | The number of people successfully recruited | Absolute number and proportion of target audience | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | Cost per person with awareness raised | N/A | Unit cost of raising awareness | £ |

| ✔ | Cost per person with behaviour change | N/A | Unit cost per behaviour change | £ | ||

| ✔ | Cost per EOI | Online and/or Offline | Unit marketing cost per EOI | £ | ||

| ✔ | Cost per completion or registration | Online and/or Offline | Unit cost per completion/registration | £ | ||

| ✔ | Cost per applicant | Online and/or Offline | Unit marketing cost per applicant | £ | ||

| ✔ | Cost per recruit | N/A | Unit marketing cost per successful recruit | £ | ||

| ✔ | ✔ | Current ROI | N/A | Unit benefit multiplied by # of behaviour changes | £ and X:Y | |

6. LEARNING AND INNOVATION

What is Learning and Innovation?

Formal learning forms the final stage of an evaluation cycle. At this stage, you would evaluate the effectiveness of inputs at each stage of the evaluation cycle to understand the impact on policy/organisation objectives and see what did or did not work. Formal learning can be used to drive innovation in the future. It would be useful to consider what approaches could be employed in future activities to overcome difficulties and leverage strengths in your approach. Where applicable, it is also useful to capture what innovations were applied in your communication activities and why they did or did not work.

For paid-for campaigns, this stage is where learnings from your 10% innovation investment should be reported in your evaluation. It is an opportunity to showcase innovations that could be “scaled up” across other communication activities but also to report other learnings (i.e. what didn’t work). The aim of this stage is not to justify new approaches but rather to inform future considerations.

If objectives or KPIs were not met, what reasons can be identified to explain the variation? If the objectives were surpassed, what has driven that? This identifies strategic insights and learnings that can be taken forward and shared.

Why learn and innovate?

This is so that, now or in the future, communications activities can capitalise on successful communication techniques and avoid embedding unsuccessful methods.

Learnings that can be applied or scaled more generally should also be shared GCS-wide, across teams, and across government organisations. You should opt for methods most suited to the needs and culture of your organisation, which may be:

- Linking up your corresponding policy teams or other teams with a similar remit to initiate discussions.

- Creating end-of-campaign reports to share on evidence repositories.

- Sharing bite-size insights via show-and-tell sessions, etc.

Example of Evaluation Metrics: from Stage 1 to 6

The following examples are fictitious and only to demonstrate the evaluation cycle.

| Campaign to encourage take-up of home insulation subsidy | |

| INPUTS | Objectives Policy objective: improve wellbeing and reduce the cost of heating during winter by ensuring people’s homes are properly insulated. Behaviour: For eligible people to have their homes insulated. Comms objectives: 1. To raise awareness of the grants available among eligible people by at least 25% in 6 months. 2. To increase grant applications through GOV.UK from 40,000 by 50% in 6 months. Learnings and insights Previous learning: infographics are an effective way to present complex information. Audience insight: Young families and people aged over 65+ in older less efficient homes are most in need of the subsidy. Planning: Online campaign with messaging targeted for different key audiences. |

| OUTPUTS | 85% of the estimated 2,000,000 people eligible for the home insulation subsidy have been reached with social media impressions. Facebook was most effective at reaching the target audience of young families. |

| OUTTAKES | Awareness of the home insulation subsidy increased by 27% from 38% to 65%.Awareness was higher among young families (68%) compared to those aged over 65 (59%).Following the innovation of a leaflet element to the campaign – Recognition of the leaflet was 18% and significantly higher among over 65’s (26%). Overall, 79% of those who reconsidered the campaign were likely to take action in the future. |

| OUTCOMES | Applications for the subsidy increased by 50% to 60,100, with 11% coming directly from Facebook advertising. |

| IMPACT | Objectives were met and targets should be increased if the campaign continues. Increased application of the home insulation subsidy means the homes of more people are likely to undertake the behaviour of insulating their homes resulting in the improvement of people’s physical health and quality of life. |

| Continuous learning | Awareness of the campaign was significantly lower amongst adults aged 65+ meaning they are less likely to apply for the subsidy. When looking at this age group in more detail it was found that the campaign generated 5x less reach amongst this age group on paid social media. Change based on learning – It was decided to adapt the inputs and engage with Age UK as a stakeholder to produce a leaflet and promote through their channels. |

| Learning and Innovation | Engaging with key stakeholders, and a targeting leaflet campaign, was more effective at reaching the audience members aged over 65, raising awareness to 63%. This should be considered in future communications. |

Linking the Evaluation Cycle and OASIS

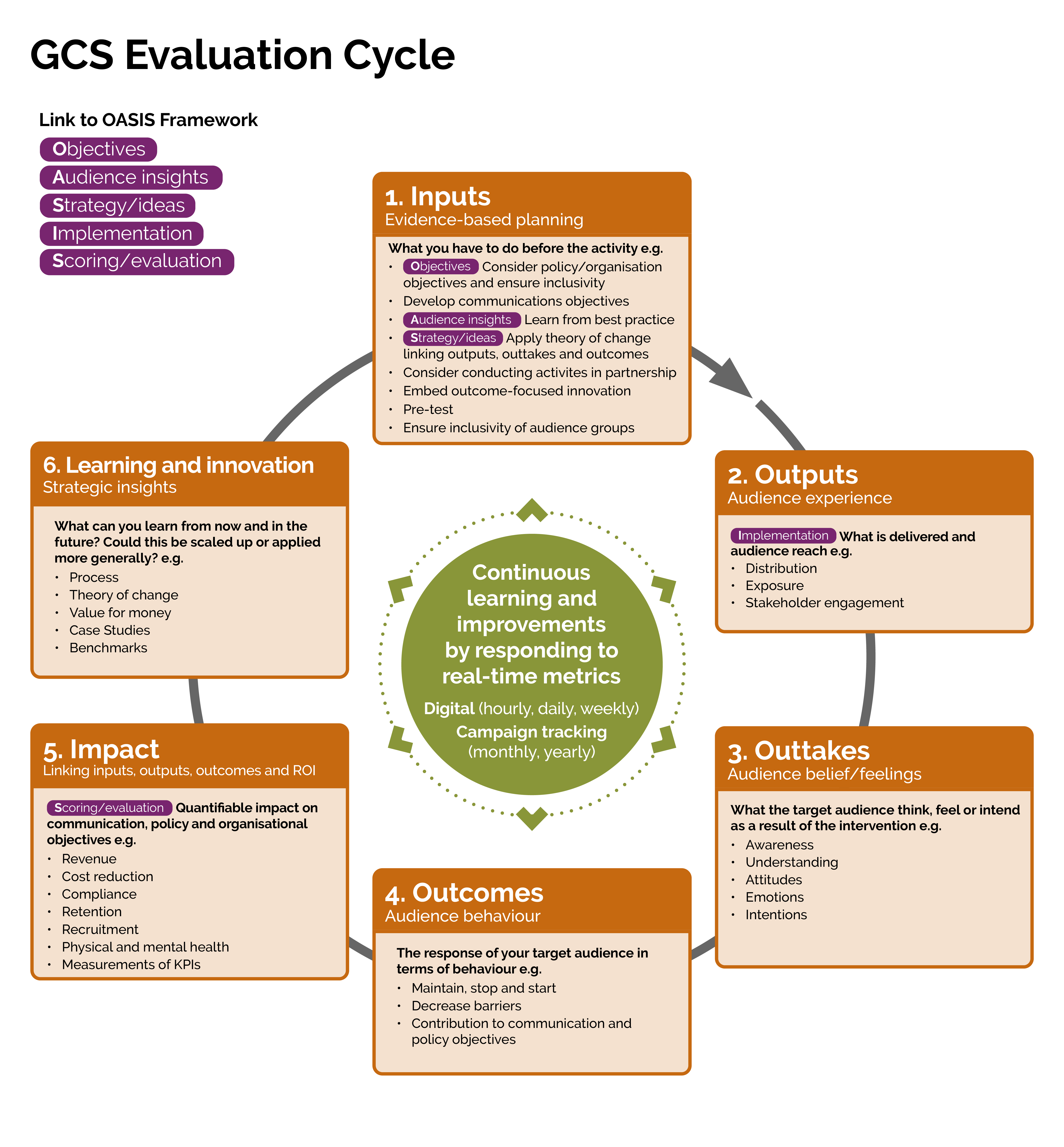

OASIS is GCS’s 5-step campaign-planning framework that helps communicators develop and implement effective campaigns, regardless of size or budget.

See full details of OASIS on the GCS website.

The five steps are:

- Objectives: what do you want the campaign to achieve?

- Audience/insight: Who are you trying to reach with the campaign? What are their needs, wants, and concerns? What barriers need to be overcome?

- Strategy/Ideas: What are the best ways to reach your audience and achieve your objectives? Consider COM-B and Theory of Change frameworks in your planning.

- Implementation: How will you put your strategy into action?

- Scoring/Evaluation: How will you measure the success of your campaign?

While evaluation seems to only form the final part of the campaign planning process, it is recommended that you plan how to evaluate your campaign at the start.

Thinking about evaluation at the beginning of your planning process has key benefits:

- You can be clear about the objectives you want to achieve with your communication activity from the start, helping you identify and collect the right data throughout. This may involve tracking website traffic, social media engagement, survey responses, etc., which are all outlined in the recommended/potential metrics table in the section above.

- Your evaluation can run concurrently with the communication activity, meaning learnings from your work can immediately create positive changes in your current campaign rather than only informing future communications.

The table and diagram below outline how the OASIS framework for campaign planning is directly linked to the stages in the Evaluation Cycle. Integrating evaluation into your OASIS planning draws clear links with policy objectives and KPIs. It also ensures learnings are built into the planning stages.

| Evaluation stage | Evaluation considerations | |

| Objectives | INPUTS | – Are your communication objectives SMART? – Are your communication objectives well-linked to your policy and organisation objectives? |

| Audience/Insight | – What is the best practice in reaching this particular audience group? – Have you chosen the correct channel to most effectively reach out to this audience group? – Does the narrative resonate with this audience group? | |

| Strategy/Ideas | – Does your Theory of Change correctly predict the cascade of events from the INPUTS to IMPACT stage? – Do the assumptions within your Theory of Change reflect your audience group’s actual behaviours? – Are there any unintended consequences or serendipities? The IN-CASE framework can help to identify unintended consequences. | |

| Implementation | OUTPUTS | – Did all components/stages/subactivities of your overall communication activity go as planned? – Are there any unanticipated challenges that may derail your communication activity? – Do we need extra safeguards against any barriers? |

| Scoring/Evaluation | IMPACT | – Did reaching your communication objectives contribute positively to your policy and organisation objectives? – If a communication activity is not helping with a policy’s cause, is there more one can do with comms? Or, are there inherent limitations to what comms can achieve towards the policy? |

Diagram B illustrates linkages between the Evaluation Cycle and OASIS. By understanding how these concepts are linked across the two frameworks, GCS colleagues should aim to collaborate more effectively and efficiently by devising campaign plans and evaluation plans concurrently.

Building in Inclusivity and Audience Segmentation

Audience segmentation is crucial to understanding your target audience’s characteristics, needs and interests.

Dividing your target audience into smaller segments based on their commonalities and differences helps you include and target hard-to-reach audiences. For example, by considering the appropriate language, tone, communicative channels, time, occasion, etc, to cater to each audience segment.

Audience segmentation can help to:

- Target your audience segments more efficiently by focusing your resources on the audience most likely to respond to your messaging.

- Ensure inclusivity for difficult-to-reach audience segments that are defined by subcultural norms.

- Increase audience engagement by presenting messages relevant to their interests and needs and fostering better audience-messenger relationships and reputation.

- Increase effectiveness by using messages that break down key barriers and subsequently lead to better Outtakes, Outcomes and Impact.

Methods of Audience Segmentation

The table below breaks down methods of segmenting your audience.

| By demographics | By golden questions | By behavioural barrier | |

| Description | Based on factors such as age, gender, location, income, education level, occupation, etc. | Using a set of questions set in a particular order to gauge your audience’s needs, interests, and behavioural norms. | Based on factors that may span demographics, e.g., motivation, perceptions and capability. |

| Pros | Data is relatively easy to collect or readily available from databases. | Provides deep insights into the audience’s needs and interests. With message targeting not bounded by demographic characteristics, you can cater even to subcultural norms. | Suitable for behaviours that are not significantly driven by demographic factors (e.g., where members of the same demographic group do not share interests or needs). If you have already done this analysis as part of your planning, then it’s readily available to help with segmentation. |

| Cons | Prone to over-generalisation, where members in the same demographic group may not have the same interests or needs. | Golden questions are tailored to each campaign, which is generally more time-consuming and expensive to implement. If they are not done carefully, it can lead to smaller, less robust segments. | You will usually have to create bespoke surveys to measure behavioural barriers as they aren’t routinely measured in the same way as demographic factors like age and income. |

Full details of audience segmentation can be found on the GCS website.

Monitoring your audience at every stage of the cycle

Audience segmentation should be considered at the beginning of the Evaluation Cycle during your communication planning (Inputs). This will allow you to report metrics for each of your audience segments throughout the evaluation cycle. Setting out segments prior to campaign activity can allow for achievable targets for each group, meaning more detailed evaluation especially where campaigns are targeted. Any learnings should take into account the audience segmentations made and whether adaptations can be made to your Outputs as communication activity progresses to maximise success in achieving your desired Outtakes, Outcomes and Impact among audience segments.

It may be beneficial to set out your assumptions and predictions for how your different audience segments will experience your communication activity (“Outputs”) and how this is predicted to change their respective beliefs or feelings (“Outtakes”), and ultimately lead to the desired audience behaviour (“Outcomes”) in a Theory of Change.

Theory of Change for Evaluation

The full guidance on Theory of Change can be found in the Magenta Book on GOV.UK. The Theory of Change for communication activity helps you capture considerations, assumptions and predictions about how your communication activity is expected to deliver behaviour change. Some key considerations during the stages of evaluation are:

- Outputs – The experience and reach of your communications/messaging among different audience groups and how this might affect your audience in terms of capability, opportunity and motivation to engage in the behaviour change as you predict.

- Outtakes – How your communications/messaging with the target audience leads to changes in beliefs and/or feelings. For example, the extent to which your audience agrees with your view/position before and after exposure to the communication activity.

- Outcomes – If your assumptions are supported by the evidence collected and behaviour change is observed as predicted.

Diagram C illustrates where audience segmentation feeds into Inputs, Outputs, Outtakes and Outcomes.

Linking the Evaluation Cycle to COM-B for Behaviour Change

In communication activities that aim to drive behaviour change, one of the more challenging parts of the evaluation cycle is establishing how progress is made from “Outputs” to “Outcomes”.

During the Inputs stage of the Evaluation Cycle, you need to plan ahead and envisage how audience experience (“Outputs”) will lead to audience beliefs and feelings (“Outtakes”) that align with the message of your communication activity, which ultimately lead to the desired audience behaviour (“Outcomes”).

A behaviour change campaign will need to address barriers that might stop your target audience from engaging in the desired audience behaviours. The COM-B model identifies three barriers:

- Capability – whether your target audience has the right knowledge, skills, physical and mental ability to carry out the behaviour.

- Opportunity – whether your target audience has the right resources, and the right systems, processes and environment around them to empower them to undertake the behaviour.

- Motivation – whether your target audience wants to or believes that they should carry out the behaviour and establish habits based on it.

By setting out a strong basis for your audience experience (“Outputs”) that adequately addresses these three barriers, you will maximise the chances of them engaging in the desirable Behaviour.

You should consider all other examples outlined in GCS’s guide to the COM-B model.

Diagram D illustrates how COM-B, OASIS and Theory of Change are built into the framework.

Additional Considerations

Calculating Return on Investment (ROI)

GCS recommends using the following five-step process:

- Objectives: These should be focused on quantifiable behavioural outcomes (such as the number of direct foreign investments generated, or the number of teachers recruited).

- Baseline: Establish the status quo or expectation for the metrics in question if we do nothing.

- Trend: A forecast of how the baseline will naturally move over the period of measurement. For example, if there has been an 8% reduction in the adult smoking rate over the last 15 years, we expect that the next year will see a 0.5% reduction, all other things being equal.

- Isolation: Exclude or disaggregate other factors that will affect the outcome you are measuring to make sure that the change observed has been caused by the campaign.

- To accurately assess the impact of a recruitment campaign, compare new hires to the existing employment rate.

- Communication activity that is accompanied by a tax or legislative change should try to apportion the total observed effect between the different methods of government policy implementation

- Externalities: Consider how well your campaign achieved your intended outcomes. On top of that, be aware of and track unintended effects – they can be positive serendipities or negative consequences. For example, the launch of a smoking discouragement campaign could aim to promote citizens’ health and alleviate stress in the healthcare system. A serendipity may be improved air quality in city parks, and an unintended consequence may be increased substance abuse in other forms, e.g., alcohol.

Assumptions

Assumptions often form a core part of calculating ROI. Assumptions should be reasonable, clearly identified and, if possible, justified. Part of the post-campaign evaluation will involve refining assumptions and considering their validity.

ROI: a worked example

The following example is fictitious, only to demonstrate the process.

The Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) is running a campaign costing £3 million to reduce the volume of inappropriate A&E attendances for low-urgency cases. The campaign aims to divert people to a GP surgery where they can be better and more efficiently taken care of.

- Objectives

The campaign will reduce the number of inappropriate NHS England A&E attendances by 3% or 85,000 in 2018/19 compared to the 2017/18 baseline of 2,865,377. - Baseline

The appropriate baseline for comparison here is the previous 12 months of operational data or observations. In 2017/18 there were 23,878,145 A&E attendances in England. 12% of these were found to be “inappropriate” (did not require A&E attendance as could have been handled by a GP or pharmacist). The baseline for inappropriate attendances is 2,865,377 (23,878,145 × 0.12). - Trend

Over the past three years, we have seen a steady increase in A&E attendances of 2% year-on-year, driven by population growth and other factors. We can forecast 24,355,708 attendances (23,878,145 x 1.02) in 2018/19. The rate of inappropriate attendance has remained broadly constant at 12%. The trend-adjusted baseline for inappropriate attendances is therefore 2,922,685 (24,355,708 × 0.12). - Isolation

The NHS is also starting to provide and promote out-of-hours GP surgery appointments. The rate of inappropriate A&E attendance is 4.5 percentage points higher than average at times when GP surgeries are not currently open. We assume that the new offer of out-of-hours service by GPs will reduce the total number of inappropriate attendances by 2.25 percentage points (half of the total observed effect because this only affects half the hours in a day). We expect this to independently reduce the number of inappropriate attendances observed by 65,760 (2,922,685 × 0.0225) to 2,856,925. - Externalities

Aside from the direct cost benefit of optimising points of treatment across NHS frontline services (in the conclusion), there are indirect benefits or positive externalities that should be considered in this case. Inappropriate attendances rarely have to be treated, so there will be a negligible cost for this, and operational overheads will remain as a fixed cost. A reduction in inappropriate A&E attendance of 3% is approximately equivalent to a 3% uplift in staffing resources (which can be redeployed to urgent cases). The total annual cost of A&E operation is £2.7 billion and staffing makes up 30% of this, which is equal to £810 million. 3% of £810 million is equal to £24.3 million. The indirect benefit of optimising A&E attendance, or the effective “opportunity cost” of not optimising staff resources, is £24.3 million.

In conclusion, the average cost of an A&E attendance is £148. The average cost of a GP appointment is £46. Therefore, every potential A&E attendance that is redirected to a GP reflects a saving to the NHS of £102 (£148 – £46).

If 85,000 cases are redirected in this way, the health service overall will be £8,670,000 (£102 × 85,000) better off.

The positive externalities generated also create £24.3 million of value for the public sector and society.

The total benefit of this campaign, or return on investment, will be £32.97 million. For every £1 spent on this campaign, society will be £11 better off. This is commonly expressed as a ratio, in this case, 11:1.

These results can be validated after the campaign has run by comparing the actual number of inappropriate A&E attendances with the isolated trend-adjusted baseline of 2,856,925.

Measuring Reputation

The reputation of an organisation is now well established as an indicator of organisational success. Positive reputations are associated with supportive behaviours from stakeholders, while negative reputations are associated with less support or even hostile responses from stakeholders. Despite good evidence on this link, there is still much confusion about how to best measure and manage reputation, with many seemingly competing models and approaches.

Assessing organisational reputation serves as an essential tool to gauge performance and inform strategic decisions. Through this section, informed by over 20 years of insights from the John Madejski Centre for Reputation, we aim to simplify the process.

When considering reputation management, remember to consider:

- Whose opinion matters most regarding reputation

- What specific elements of the organisation’s reputation are under scrutiny

- How managing these elements of reputation will help you achieve your policy objectives

Identifying Your Audience

Organisations have different reputations with different groups and individuals. Identifying which stakeholders are integral to your mission is imperative. This selection must be guided by an understanding of your organisation’s objectives and whom it intends to serve. Factors such as the influence and legitimacy of these stakeholders, as well as the urgency of their concerns, should inform your response. In the dynamic landscape of stakeholder engagement, prioritise judiciously rather than reacting to the most vocal demands, which are frequently amplified by social media platforms.

It is therefore important to consider aspects of organisational purpose, stakeholder need, and legitimacy before responding to stakeholders and when managing and measuring reputation. At its best, choosing to measure reputation with a particular group can help to give them a voice, allow your organisation to listen, and guide and justify the actions of your organisation.

Focusing on Reputation Elements

In practice, reputation is often measured as an aggregate of stakeholders’ trust and respect for an organisation. This is sometimes referred to as “emotional appeal”. This aggregate measure of reputation allows organisations that are different (e.g., the armed services vs Amazon) to be compared in terms of the extent to which they are trusted.

However, reputation is also shaped by a range of aspects including;:

- organisational characteristics (e.g., products, leadership, financial performance)

- relationships (e.g., customer service, listening, the appropriate use of power)

- third party influence (e.g., whether important third parties recommend your organisation)

Understanding and measuring these underlying drivers is vital for creating effective change strategies. They can be defined and measured as the causes of reputation that make stakeholders trust or respect your organisation. Where data allows, measuring these factors and causally linking them to reputation through multivariate statistical analysis is important in helping to develop a Theory of Change. For example, if good service experience is found to be a key factor driving trust in the HMRC, it would be reasonable to focus activities on service if it was cost-effective.

Purpose-Driven Reputation Management

Reputation management strategies should be aligned with the behavioural outcomes you aim to achieve among stakeholders. Whether you are encouraging certain actions, discouraging others, or maintaining desirable behaviours, the desired change must be clearly articulated. Rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all approach, tailor your strategies to specific contexts and stakeholder groups, and recognise that maintaining existing positive behaviours is typically more straightforward than instigating new actions or dissuading entrenched habits.

Measuring Your Progress

It is important to measure not only reputation but also its causes and consequences in a way that allows you to establish robust correlations. Employing tried-and-tested measurement scales and analytical techniques, such as multivariate regression, will enable you to discern which experiences influence reputation and subsequent behaviour patterns. In this way, you will be able to identify which stakeholder experiences link to reputation and its associated consequences. It is also important to include measures that benchmark your organisation against other organisations, especially in terms of aspects of trust and respect.

Overall, knowing your audience, understanding what shapes your reputation, and being clear on your goals will greatly improve your reputation management.

Library of Further Resources

- OASIS / Guide to Campaign Planning

- COM-B / The Principles of Behaviour Change Communications

- Magenta Book

- Data Ethics Framework

Reference List

- Fernandez-Muinos, M., Money, K., Saraeva, A., Garnelo-Gomez, I., & Vazquez-Suarez, L. (2022). “The ladies are not for turning”: Exploring how leader gender and industry sector influence the corporate social responsibility practices of franchise firms. Heliyon, 8.

- Garnelo-Gomez, I., Money, K., & Littlewood, D. (2022). From holistically to accidentally sustainable: A study of motivations and identity expression in sustainable living. European Journal of Marketing, 56(12).

- Ghobadian, A., Money, K., & Hillenbrand, C. (2015). Corporate responsibility research: Past – present – future. Group & Organization Management, 40(3), 271-294.

- Hillenbrand, C., Money, K. G., Brooks, C., & Tovstiga, N. (2019). Corporate tax: What do stakeholders expect? Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 403-420.

- Hillenbrand, C., Saraeva, A., Money, K., & Brooks, C. (2020). To invest or not to invest? The roles of product information, attitudes towards finance and life variables in retail investor propensity to engage with financial products. British Journal of Management, 31(4), 688-708.

- Hillenbrand, C., Saraeva, A., Money, K., & Brooks, C. (2022). Saving for a rainy day… or a trip to the Bahamas? How the framing of investment communication impacts retail investors. British Journal of Management, 33(2), 1087-1109.

- Mason, D., Hillenbrand, C., & Money, K. (2014). Are informed citizens more trusting? Transparency of performance data and trust towards a British police force. Journal of Business Ethics, 122(2), 321-341.

- Money, K., & Hillenbrand, C. (2006). Using reputation measurement to create value: An analysis and integration of existing measures. Journal of General Management, 32(1).

- Money, K., & Hillenbrand, C. (2024). A Review of Current Practice and Future Directions for Evaluation within and across the Government Communication Service. Henley Business School: The John Madejski Centre for Reputation. https://assets.henley.ac.uk/v3/fileUploads/Money-Hillenbrand-Review.pdf

- Money, K., & Hillenbrand, C. (forthcoming). Trends and approaches in the evaluation of communication in government and the charity sector: evaluation as a cycle of continuous improvement.

- Money, K., Hillenbrand, C., Henseler, J., & da Camara, N. (2013). Exploring unanticipated consequences of strategy amongst stakeholder segments: The case of a European Revenue Service. Long Range Planning, 45(5-6).

- Money, K., Hillenbrand, C., Hunter, I., & Money, A. G. (2012). Modelling bi-directional research: A fresh approach to stakeholder theory. Journal of Strategy and Management, 5(1), 5-24.

- Money, K., Saraeva, A., Garnelo-Gomez, I., Pain, S., & Hillenbrand, C. (2017). Corporate reputation past and future: A review and integration of existing literature and a framework for future research. Corporate Reputation Review, 20(3-4).

- Saraeva, A., Hillenbrand, C. & Money, K. (forthcoming). Reputation as buffer, booster and boomerang. How reputation adds value in different circumstances. European Management Review.

- West, B., Hillenbrand, C., Money, K., Ghobadian, A., & Ireland, R. D. (2016). Exploring the impact of social axioms on firm reputation: A stakeholder perspective. British Journal of Management, 27(2).